Canadians in Buxton ;An indigenous officer in Buxton

From time to time, I come across additional bits of information, which I think I could have included in the book “Maple Leaves in Buxton”. Probably, I could have kept adding more, which would have meant I never published it. So we can continue to add some interesting updates on the website and who knows in the unlikely event of a second edition , I can include those as well. Having looked at Canada’s oldest solder who passed through Buxton in the last article , it is worth looking at the story of Oliver Milton Martin, a Mohawk Army officer , who was a patient in the Granville Special Hospital in Buxton and later at the Matlock Bate Convalescent Hospital for officers.

More than 4,000 First Nations soldiers fought for Canada during the war, officially recorded by the Department of Indian Affairs. In addition, thousands more non-Status Indians, Inuit, and Métis soldiers enlisted without official recognition of their Indigenous identity. (status Indians or registered Indians were people registered under the Indian Act having rights and benefits not granted to other First Nations people, Inuit, or Métis, No-status Indians were therefore not registered ). Between August 1914 and December 1915, relatively few First Nations men volunteered, as the army was hesitant about recruiting them for fear the “Germans might refuse to extend to them the privileges of civilized warfare.” Despite this at least 200 did manage to enlist. After December 1915, the British government asked its Dominions to actively recruit Indigenous soldiers. . The enactment of conscription in 1917, which included Status Indians, sparked great protest from First Nations peoples. In response, the government granted a limited exemption from overseas combat service for Status Indians in January 1918. As mentioned By war’s end, Indian Affairs estimated 4,000 First Nations men enlisted, but their records were incomplete and omitted non-Status Indians and Métis people. While speculative, the total figure for 1914-18 could have been closer to 6,000,. Historians estimate that 35 per cent of the Status Indian population of military age voluntarily enlisted for overseas service, comparable to the percentage of non-Indigenous men who volunteered for duty.

Some Canadian regiments boasted large numbers of Indigenous soldiers, including the 114th Battalion ("Brock's Rangers") and the 107th “Timber Wolf” Battalion. However, Indigenous soldiers were mostly integrated into regular military units, rather than serving in segregated “all-Indian” units. The war meant that Indigenous and non-Indigenous soldiers interacted to a degree not experienced in pre-war Canada. For some, the culture shock of transitioning to military life and discipline proved difficult, and those who disobeyed army regulations were disciplined or even discharged. However, the vast majority of Indigenous recruits became successful soldiers, with at least 37 decorated for bravery in action. It stands to reason that some wounded or indigenous soldiers may have passed through the Canadian hospitals in Buxton ( The Canadian Special Red Cross Hospital and the Granville Special Hospital) or through the Canadian Discharge Depot, Since around 20,000 Canadians passed through Buxton, without records of individual payments identifying indigenous soldiers from other ranks would be looking for a needle ina haystack, so i was fortunateto stuble across the story of Oliver Milton Martin.

Oliver Milton Martin, was born 9 April 1893, in Ohsweken, in the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation. Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario, is the common name for both a reserve and a Haudenosaunee First Nation. The reserve is just over 182 km2, located along the Grand River in southwestern Ontario. Six Nations is home to the six individual nations that form the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Confederacy (Haudenosaunee). These nations are the Kanyen’kehaka (Mohawk), Onyota’a:ka (Oneida), Onöñda’gega’ (Onondaga), Gayogohono (Cayuga), Onöndowága’ (Seneca) and Skaru:reh (Tuscarora)

He was one of seven children born to Robert and Lucinda “Lucy” Martin (nee Miller). His early education was at a school on the Six Nations Reserve and Caledonia High School. With so many children in the family, Martin left home as a teenager and found work in a drugstore in Rochester, New York. A desire to teach and the persuasion of a friend convinced him to return to Canada. Martin graduated from Normal School (teacher’s college) and began teaching. In 1909, he joined the 37th Regiment Haldimand Rifles, a local militia unit, as a bugler. Martin served with the unit for three years and was commissioned as a lieutenant. On 9 February 1916, Oliver Martin enrolled in the 114th (Brock’s Rangers) Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force as a lieutenant. The unit recruited in Haldimand County had its secondary title in honour of the Indigenous warriors from the Grand River region who fought beside Major-General Sir Isaac Brock during the War of 1812. Martin sailed from Halifax with the battalion on 31 October 1916 and arrived at Liverpool on 11 November. The 114th Battalion was broken up shortly after arrival in England and its soldiers sent to various units as reinforcements. In January 1917, after brief attachments to other battalions, Martin was posted to the 107th (Timber Wolf) Battalion. The 107th Battalion had been raised in Western Canada and contained several Indigenous soldiers. It was redesignated as a pioneer unit in England before it was sent to France in March 1917.

The battalion was based at Écoivres and Maison Blanche doing pioneer tasks prior to the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917. On 15 August, the 107th battalion was engaged in the Battle of Hill 70, where it followed the leading assault troops. Of the 600 soldiers engaged, 21 were killed and approximately 140 wounded. After this battle, one company volunteered to search for and bring in the dead and wounded. In all, the company recovered 30 dead and carried 25 wounded to dressing stations, for which the soldiers received high praise. Two First Nations soldiers, privates A.W. Anderson and O. Baron, were awarded the Military Medal for bravery for this action. In September 1917, Martin was attached as a probationary observer with the Royal Flying Corps and sent on a month-long observer’s course in England.

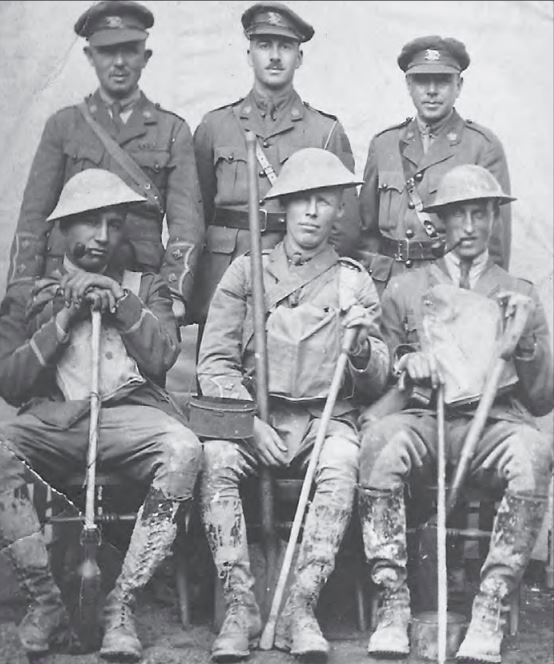

Oliver Martin with other officers from the 107th Battalion

In November 1917, Martin was admitted to 1st Northern General Hospital in Newcastle upon Tyne complaining of urinary, knee and hip pain. While in Newcastle, he married Irene Preece, with whom he had a daughter in 1918. After Newcastle, Martin was sent to the Granville Special Hospital in Buxton and the convalescent hospital in Matlock Bath while recovering from his medical problems. In June 1918, he was attached to No. 1 School of Aeronautics in Reading, where he earned his Royal Air Force pilot’s wings. After repatriation to Canada in July 1919, Oliver Martin applied for federal government funding designated for Indigenous people so he could attend university but was unsuccessful. He then tried to put himself through the University of Toronto but returned to teaching in 1922. He first taught at Secord School in East York, a Toronto suburb. Martin and Irene divorced in the early 1920s, and she returned to England with their daughter.

Martin continued to teach at Secord until 1936. While there, he married fellow teacher Lillian Bunt in 1936, but they had no children. Martin went on to become the principal of the nearby Danforth Park School. Martin also rejoined his old prewar militia unit, the Haldimand Rifles. He rose through the officer ranks and assumed command in 1930 as a lieutenant-colonel. In 1936, the Haldimand Rifles amalgamated with the Dufferin Rifles to form the Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles of Canada. Martin remained as commanding officer of the new unit until the outbreak of the Second World War. Oliver Martin remained in Canada during the Second World War and led three home defence brigades. He commanded 13th Infantry Brigade as a colonel while it underwent training at Niagara-on-the-Lake from June 1940 to August 1941. The brigade was then sent to Vancouver Island over fears of a Japanese invasion after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on 7 December 1941. Promoted brigadier in 1941, Martin was also sent to the West Coast. He commanded 18th Infantry Brigade at Nanaimo, BC, between August 1941 and May 1942, followed by 16th Infantry Brigade at Prince George, BC, from May 1942 to July 1943. His last appointment was in command of troops in Military District No. 2 in Ontario. Martin retired from the army in October 1944.

In 1944, after he left the army, the government of Ontario appointed Oliver Martin as provincial magistrate for York, Halton and Peel Counties, collectively known as District 6. He was the first Indigenous individual to hold a judicial post in the province. In 1953, Martin and his wife attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II as invited guests. He died in hospital in 1957 following an operation and is buried in the veteran’s section of the Pine Hills Cemetery in Scarborough, Ontario. As the first Indigenous person to be promoted brigadier (known as brigadier-general since 1968) and appointed provincial magistrate, Martin was a trailblazer, and most discussions and lists of prominent Indigenous people in Canada include his name. He was made a member of the Indian Hall of Fame, a display created at the Canadian National Exhibition to honour Indigenous people that ran for several years.

Oliver Martin as a Brigadier in WW2

On Canadian Hospitals in Buxton

Maple Leaves in Buxton - robertspublications

Oliver Martin's Service records

MARTIN, OLIVER MILTON (2 digital object(s)) Genealogy / Military / First World War Personnel Records

Indigenous Soldiers of the First World War

Indigenous Peoples and the First World War | The Canadian Encyclopedia