Canada’s Oldest Soldier passed through Buxton

I wish I had found this story before finalizing Maple Leaves in Buxton, I would have incorporated the fascinating story of John William Boucher who was certainly Canada’s oldest soldier in WW1 and possibly the oldest soldier in the whole war .He was also possibly the only veteran of the US Civil War to pass through Buxton .

Younger soldiers might have lied about their ages to appear older, in the book I told the story of

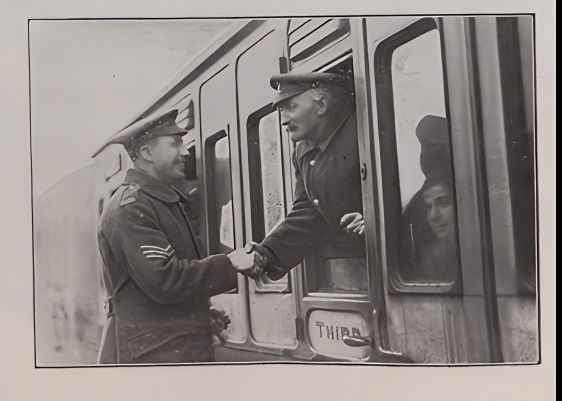

Nathan Doughtery, an under age soldier who met a tragic and unexplained death in a Buxton Reservoir. There were also one or two older soldiers who deducted a few years off their ages, John William Boucher went further and shaved a couple of decades off his age to enlist with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. A photo in the Canadian Discharge Deport souvenir possibly taken at Buxton Station led me into his story. His Canadian service records show that after service in France he was sent to the Canadian Discharge Depot in Buxton from where he was sent to Liverpool for embarkation back to Canada.

Sapper John Boucher ( Canada's oldest soldier) leaving England ( possibly taken at Buxton Station)

On his attestation for the Canadian Army , John mentioned previous military service -without specifying where and when . Clearly, he could not admit to having served in the US Civil War, since on the same attestation he was claiming his date of birth as 1867 ( two years after the war finished) .By the time he was discharged his correct age starts appearing in his Canadian paperwork , with his correct date of birth in December 1844.

Boucher’s father died when he was young and he was sent to boarding school. When the US Civil War broke out, he crossed the border; and, at age 19, tried to enlist in the Union Army. “I had gone out of my way … to battle for the cause of freedom in America’s Civil War,” wrote Boucher for the Syracuse Post-Standard in 1918. Between 35,000 and 50,000 Canadians served in the Civil War, most on the Union side, even though it was technically illegal for British subjects to serve in the conflict. No formal identification cards existed at the time, so declarations of age and citizenship on enlistment were pretty much taken on trust.

Boucher first tried to enlist in Buffalo, New York where he was deemed too young, then in Cleveland, where he was rejected for causes unknown. He was finally accepted in Detroit, where he joined the 24th Michigan Infantry. He claimed to have served at the Battle of Nashville in December 1864 and through to the war’s end in April 1865.

After the Civil War, Boucher returned to Canada and started a family. He worked as a surveyor, baggageman and freight conductor for multiple railroads, even serving a stint stateside. Eventually, he settled in Gananoque, Ontario, on the northern banks of the St. Lawrence River, eight miles from the New York border. Boucher seems to have spent his middle years working in a carriage factory and as a night watchman for a metal foundry. Gananoque sounds a charming place known as “The Gateway to the Thousand Islands," which lie next to it in the St. Lawrence River”. According to a report in the Windsor Star, Boucher became a guide on the St. Lawrence. Boucher’s children grew up, and, around 1898, his wife died. By August 1914, when the First World War started Boucher was spending most of his days fishing. Instead of continuing this quiet life 52 years after his last war ended, he at the age of 72, he became one of the oldest—possibly the very oldest—men to serve on the battlefield during World War I.

Initially Boucher went to a recruiting station near his home. The enlistment officer complimented him on his “fine build and strong physique” but stated the obvious—the upper age limit for enlisted men was 45. Two years later, age 71, Boucher got a tip that the 72nd Queen’s University Battery needed a cook. “Now, I had something of a reputation as a chef,” Boucher bragged in the Post-Standard. “There were few in Gananoque … who had not sampled my dishes at one time or another.” He was denied again and begged a Canadian senator for help. No luck. He later wrote “The Canadian army was immune from politics,”

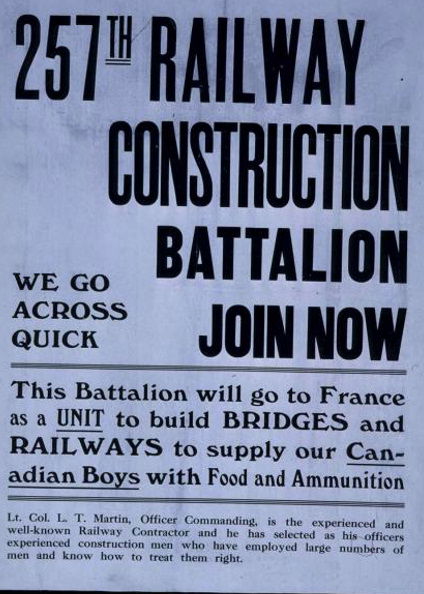

In January 1917, Boucher’s search for somewhere to enlist widened to Belleville, Ontario. The 257th Canadian Railway Battalion raised its age limit to 48, Boucher spotted an opportunity,” he said. “To be with the railroad construction battalions meant being within sight of the trenches.” He went to a different recruiting office, where he undressed, stood before the doctor, threw back his shoulders and stated his age as 48.doctor apparently replied with a smile “And then some, like myself”. Boucher passed the physical exam and, at 72, became a sapper with the Railway Battalion.

At the age of 72 , US Civil War Veteran John Boucher finally managed to join the Canadian Railway Troops

Recruitment articles in local newspapers detailed the benefits of joining the Railway Construction Battalions,

“Men who have been turned down as being unfit, now have a chance to serve their country by enlisting in the 257th Railway Construction Battalion. The medical standard of this battalion is reduced from that demanded for service in the trenches, while the age limit is extended to 48 years.The battalion is being organized by Lieut.-Col. L. T. Martin, who is himself a well-known railway constructor from Renfrew, and has engaged in many large enterprises. The headquarters of the battalion is stationed in Ottawa and the officers are all practical railway construction men, who have volunteered to form this corps for railway work in France, or wherever it is needed back of the front.Though the battalion has been authorized for only two weeks, one company of men have already been secured. As soon as the battalion is up to full strength it will without further training be sent direct to France, where it will be employed on Railway construction work. The following is the list of the class of men wanted for the battalion.Foreman. General foremen, walking bosses, excavation, rock work, drilling, track-work, steel bridge, timber trestle, concrete, master mechanics, shovel, pile driver, rigging, etc., etc.Mechanics. Carpenters, timber farmers, pipe fitters, mechanics, hoist runners, dinkey skinners, firemen, shovle runners, drillers, driller helpers, powder men, blacksmiths, steel workers, riggers, all kinds of handy men, laborers, etc.”

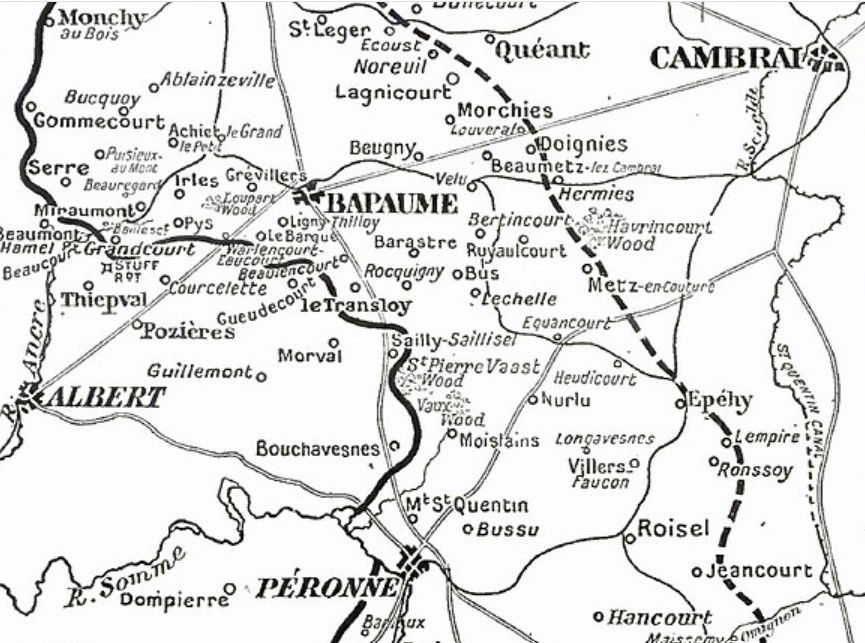

The battalion embarked for England on 16 Feb 1917 under command of Lieutenant-Colonel L.T. Martin with a strength of 29 officers and 902 OR’s where on 8 March 1917 it was redesignated as the 7th Battalion Canadian Railway Troops ( CRT). Boucher remained at the CRT Depot in Purfleet until he was taken on the strength of the 6th Battalion CRT and sent with them to France on 5 May . Boucher then spent 6 months with the 6th Battalion on the Western Front. On joining the 6th Battalion, Boucher was sent to the Pas De Calais. According to the War Diary, they were based in the area near to Lechelle, around Metz en Couture and Gouzeacourt, towards the Hadrincourt forest. Two salients had been formed during the Battle of the Somme in 1916 between Arras and Saint-Quentin and from Saint-Quentin to Noyon. In early 1917 the Germans planned a strategic withdrawal to new positions on the shorter and more easily defended Hindenburg Line (Siegfriedstellung). The withdrawal took place between 9 February and 20 March 1917, after months of preparation. The German retreat from the Bapaume and Noyon salients shortened the Western front by 25 mile, freeing 13 to 14 extra divisions for the German strategic reserve, then being assembled to defend the Aisne front against the planned Franco-British Nivelle Offensive. In the area to be abandoned railways and roads were dug up, trees were felled, water wells were polluted, towns and villages were demolished and many land mines and other booby traps were planted. Around 125,000 able-bodied French civilians in the region were transported to work elsewhere in occupied France, while children, mothers and the elderly were left behind with minimal rations. The final German withdrawal took place from 16 to 20 March giving up more French territory than that gained by the Allies from September 1914 until the beginning of the operation. The British Third Army and Fifth Army followed up and moved into Bapaume, and Péronne. After the occupation the Canadian Railway Troops were engaged in constructing and repairing railways to the new British Trench positions. Narrow -gauge Trench railways were the solution to logistical problems on the Western Front . These narrow-gauge lines, with small locomotives and rail cars, were very versatile and easier to lay.

The area around Perrone where the 6th Canadian Railway Troops were stationed

The rail crews were high-value targets for aerial attacks. “A German plane appeared over a wooded hill,” Boucher recalled. “Officers commanded us to scatter and lay flat on our faces.” During one attack, he spotted an old iron boiler and sprinted for cover. “I’d have made it all right if I hadn’t stepped into a hole. I stumbled and went sprawling on the ground and lay there with my nose buried in the earth.” The bombs kept coming, tearing the sky and blasting the fields around him. “As I look back, I am astonished that we were able to accomplish anything,” he wrote. “Very often, as fast as we laid rails, they were ripped up by an exploding shell.”After eight months of tough labour, marching and dodging enemy fire, Boucher’s age caught up with him. He was struggling with rheumatism, likely arthritis, and a Red Cross corporal ordered him to the infirmary. Boucher’s war was over.

Dismissed on the grounds of age, he returned to London to convalesce and await transfer back to Canada. While in town, he told his story to military officers, British lords and clergy members. After a time, he received an invitation to meet with King George V. On December 21, 1917, Boucher met the King at Buckingham Palace. “I simply bowed to him, without saluting, as I had no cap on and King George was dressed in civilian clothes,” Boucher recalled. “The king immediately advanced, warmly grasped my hand, and said, ‘Sapper Boucher, I am proud to meet you. It does my eyes good to see a man of your age in khaki.’”

Following his return from Europe, Boucher moved to Syracuse in upstate New Tork, where he told his story to the Posts Standard newspaper of Syracuse. Boucher survived two decades after the War ended. He died in July 1939 , just before the next war started and another generation of Canadians went to war in Europe.

After the war John Boucher moved to Syracuse, New York, where he told his story to the local newspaper

John Boucher's full story is told in the following article

On Canadian Railway Troops

The war and the 7th Bn. C.R.T. - Image 69 - Canadiana