Black Canadian Soldiers in Buxton in World War One

So in the six months or so, since “Maple Leaves in Buxton “ was published, we have actually sold a few copies, which is gratifying . Currently it is on sale at Scriveners Bookshop in Buxton, where I was happy to see some copies on display and at the Tourist Information Centre in Buxton, where they sold out there modest supply. We have even received three direct orders from Canada. I thought this was due to my skills with tagging for a Search Engine, but it turns out that on 8 November , the book got a brief mention in the Canadian newspaper. “The Globe and Mail “, as part of an article on Canadians in Buxton during the First World War. I have now stumbled across so much extra information, that a revised and extended edition is in on the cards. Typically. I was looking for something else, when I happened across the interesting story of Jeremiah Jones, a Black Canadian soldier and the long struggle to obtain his gallantry . Now Jeremiah-s connection with Buxton is fairly tenuous, he was at the Canadian Discharge Centre for around two weeks before heading back to Nova Scotia, however his story and how the Canadian Government finally righted a historical wrong seems worth retelling. And really you have to appreciate the decency of Canadians in doing this.

The Canadian Discharge Depot, Buxton

So back in November 1917, residents of Buxton may have been surprised to see a tall and distinguished black gentleman in Canadian uniform out and about in the town. He was described as strapping and looking much younger than the 58 years of age, he actually carried. Like

John William Boucher, Canada’s oldest soldier , Jeremiah had led about his age to enlist in the Canadian Army. He was actually born in 1858 in Truro , Nova Scotia , but on his attestation he told them his year of birth was 1877, saving nearly twenty years off his actual age. Jeremiah was a farmer and teamster in Nova Scotia, and apparently a healthy lifestyle had allowed him to pass for much younger. His family had migrated from the United States , where as a result of their loyalty to the Crown during the 1700s, they had been granted land by the British in Nova Scotia, and had remained there acer since. By all accounts extremely patriotic, it was not entirely surprising that Jeremiah volunteered for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. What is possibly more surprising is that he managed to be accepted, despite the enthusiasm of young black Canadians to serve their country, the prejudices of many of the white Canadians in charge of military recruitment made the process difficult.

Private Jeremiah Jones

In 1914, Arthur Alexander, an esteemed educator from North Buxton, Ontario had written to Sir Sam Hughes, the Minister of Militia asking the policy on the recruitment of Black Canadians

“The colored people of Canada want to know why they are not allowed to enlist in the Canadian Militia. I am informed that several who have applied for enlistment in the Canadian |expeditionary Forces have been refused for no apparent reason than their color, as they were physically and mentally fit “

The Military Secretary replying on behalf of the Minister replied that:

“ Under instructions already issued, the selection of officers and men for the second contingent is entirely in the hands of commanding Officers, and their selections or rejections are not interfered with by Headquarters”

It was therefore up to the Commanding Officers, if they wanted to be racist or not.

Apparently the 106th Battalion, did not operate a colour bar. The officer in charge Lt Colonel Walter Allen , had been born in Kidderminster, England and was a Boer War veteran, occupied as a carriage builder in Truro, Nova Scotia. He had already fought with the 15th Canadian Battalion in France , where he was wounded. He was then authorised to raise the 106th Battalion in Nova Scotia .Walter Allen was prepared to allow black volunteers believing that “coloured men should do their share in the empire’s defence”. Not that he was a convinced anti-racist, he subsequently tried to raise a segregated black platoon for his battalion, until finding it was against the Militia’s regulations.

Anyway Jeremiah Jones was one of sixteen black soldiers recruited into the 106th battalion and sailed for England. Meanwhile Lt Colonel Allen fell from rather spectacularly from grace , when questions were raised about the mysterious nature of the wound he had suffered in France. He was cashiered for conduct unbecoming to an officer. The inference is that his would was self-inflicted. So the 106th sailed for England under the 24 year old Lt Colonel Innes, where it was broken up and used to replace casualties in other units. Jeremiah Jones ended up in the Royal Canadian Regiment, which formed part of the Canadian 3rd Division and as a result ended up at Vimy Ridge.in February 1917.

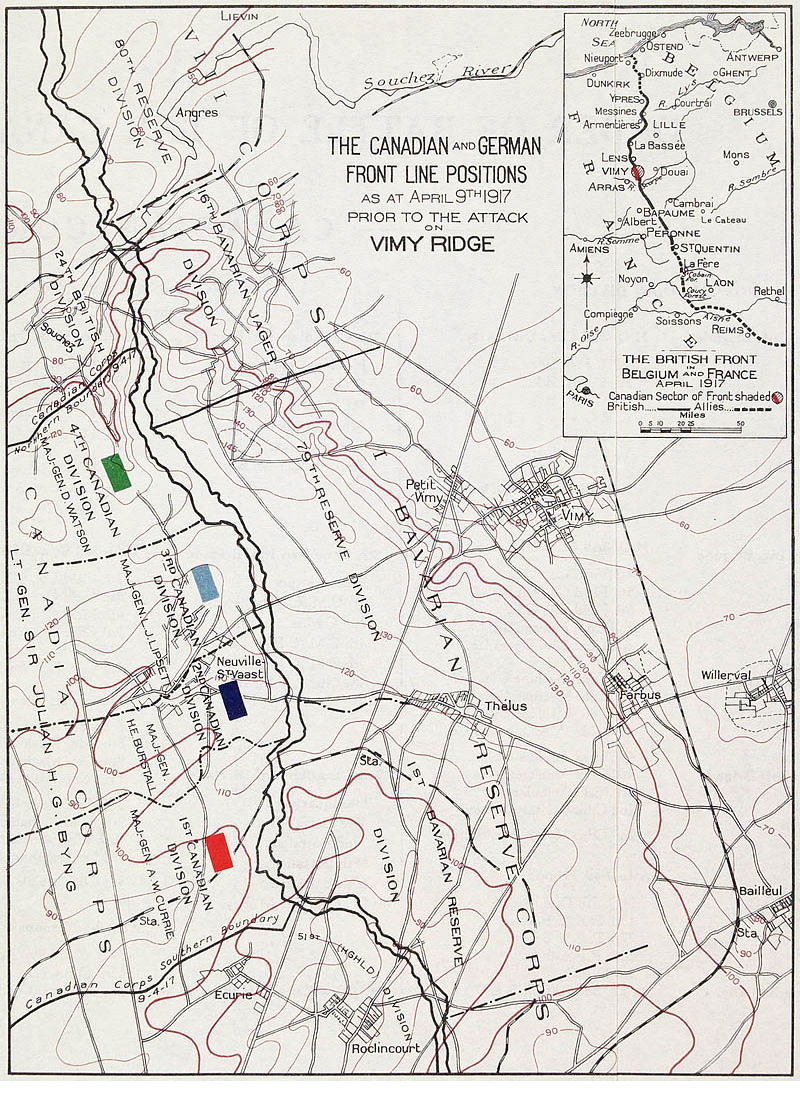

The attacking Canadian and defending German positions at Vimy Ridge

Vimy Ridge is an escarpment 8 km northeast of Arras on the western edge of the Douai Plain. The ridge rises gradually on its western side and drops more quickly on the eastern side. At approximately 7 km in length and culminating at an elevation of 145 m , the ridge provides a natural unobstructed view for tens of kilometres in all directions. The ridge fell under German control in October 1914 during the Race to the Sea, The French Tenth Army attempted to dislodge the Germans from the region during the Second Battle of Artois in May 1915 briefly capturing the height of the ridge but being unable to hold it owing to a lack of reinforcements. Another attempt during the Third Battle of Artois in September 1915,only captured the village of Souchez at the western base of the ridge. The French suffered approximately 150,000 casualties in their attempts to gain control of Vimy Ridge and surrounding territory and after that the Vimy sector calmed with both sides dig in and taking a largely live and let live approach. The French Tenth Army withdrew to reinforce Verdun.

On 28 May 1916, Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng took command of the Canadian Corps. Discussions for a spring offensive near Arras began, following a formal conference of corps commanders held at the First Army Headquarters (HQ) on 21 November 1916. In March 1917, the army HQ formally presented Byng with orders giving Vimy Ridge as the Canadian Corps objective for the Arras Offensive.

A plan, adopted in early March 1917, drew on the briefings of staff officers sent to learn from the experiences of the French Army during the Battle of Verdun.[15] For the first time the four Canadian divisions would fight together. The nature and size of the attack needed more resources than the Canadian Corps possessed and the British 5th Division, artillery, engineer and labour units were attached to the corps, bringing the nominal strength of the Canadian Corps to about 170,000 men, of whom 97,184 were Canadian.

The preliminary phase of the Canadian Corps artillery bombardment began on 20 March 1917, with a systematic two-week bombardment of German batteries, trenches and strong points. The Canadian gunners paid particular attention to eliminating German barbed wire. Only half of the artillery fired at once and the intensity of the barrage was varied to confuse the Germans about Canadian intentions. Phase two lasted the week beginning 2 April 1917 and employed all of the guns supporting the Canadian Corps, massing the equivalent of a heavy gun for every 18 m and a field gun for every 9.1 m, the German soldiers came to refer to the week before the attack as "the week of suffering“ with their trenches and defensive works were almost completely demolished. The health and morale of the German troops suffered from the stress of remaining at the ready for eleven straight days under extremely heavy artillery bombardment. Meanwhile , intelligence gathering by the Germans, big Allied trench raids and troop concentrations seen west of Arras, made it clear to that a spring offensive in the area was being prepared. In February 1917, a German-born Canadian soldier deserted and helped confirm many of the suspicions held by the Germans, providing them with a great deal of useful information. On 29 March four Canadians from the 31st Battalion were taken prisoner and gave much information under interrogation, including the plan of attack and a list of the divisions involved. The Germans knew that an offensive was imminent and would include operations aimed at capturing Vimy Ridge.

The attack began at 5:30 am on Easter Monday, 9 April 1917. During the late hours of 8 April and early morning of 9 April the men of the leading and supporting wave of the attack were moved into their forward assembly positions. The weather was cold and later changed to sleet and snow. Although physically discomforting for everyone, the north-westerly storm provided some advantage to the assaulting troops by blowing snow in the faces of the defending troops. Light Canadian and British artillery bombardments continued throughout the night but stopped in the few minutes before the attack, as the artillery recalibrated their guns in preparation for the synchronized barrage. At 5:30 am, every artillery piece at the disposal of the Canadian Corps began firing. Thirty seconds later, engineers detonated the mine charges laid under no man's land and the German trench line, destroying a number of German strong points and creating secure communication trenches directly across no man's land. Field guns fired a barrage that mostly advanced at a rate of 100 yd (91 m) in three minutes while medium and heavy howitzers fired standing barrages further ahead against defensive systems. During the early fighting, the German divisional artilleries, despite many losses, were able to maintain their defensive fire. As the Canadian infantry advanced, they overran many of the German guns because large numbers of their draught horses had been killed in the initial gas attack. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions reached the Black Line, by 6:25 am. The 4th Canadian Division encountered a great deal of trouble during its advance and was unable to complete its first objective until some hours later. After the pause when the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions consolidated their positions, the advance resumed. Shortly after 7:00 am, the 1st Canadian Division captured the left half of its second objective, the Red Line and moved the 1st Canadian Brigade forward to mount an attack on the remainder. The 2nd Canadian Division reported reaching the Red Line and capturing the village of Les Tilleuls at approximately the same time.

The advance of the 3rd Canadian Division was preceded by a mine explosion that killed many troops of The German Reserve Infantry Regiment 262 in the front line. The survivors could do no more than man temporary lines of resistance until later occupying the German third line. The southern section of the 3rd Canadian Division was able to reach the Red Line at the western edge of the Bois de la Folie at around 7:30 am. At 9:00 am the division learned of its exposed left flank and had to establish a divisional defensive flank to its north. The speed of the Canadian advance was too quick to react to in time. Despite the successes of the other Canadian Divisions, the advance of the 4th Canadian Division, collapsed almost immediately after exiting their trenches. The commanding officer of one of the assaulting battalions had requested that the artillery leave a portion of the German trench undamaged. Machine-gun nests in the undamaged sections of the German line shot down much of the troops on the right flank. The progress on the left flank was eventually impeded by harassing fire from the Pimple, made worse when the creeping barrage got too far ahead of the advancing troops. The 4th Canadian Division did not attempt a further frontal assault that the afternoon.

During the battle with Canadian troops were pinned down by German machine gun fire. Jones volunteered to attack a German gun emplacement. He managed to reach the machine gun nest, tossed a hand grenade and killed several soldiers. The remainder surrendered to him and Jones forced his captives to carry the machine gun back across the battlefield to the Canadian lines, where they were ordered to deposit it at his commanding officer's feet. For his heroics, Private Jones was reportedly recommended for a Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) which he was never awarded.

After this incident, Jeremiah was wounded in the arm. He presumably headed down the casualty evacuation chain, until he reached the 13th Stationary Hospital in Boulogne and was then taken across the channel to the 4th General Hospital in Denmark Hill and then the Canadian Convalescent Hospital in Bromley. Sent to the Canadian depot at Bramshott, Jeremiah was examined and presumably his true age came to light. Although his wound had healed, he was classified as unfit for further service and on 4 November 1917 was sent to Buxton to be discharged.

After being wounded Jeremiah Jones was evacuated to the No 4 General Hospital, Denmark Hill ( King's College Hospital)

He was sent to recover at the Canadian Convalescent hospital in Bromley, Kent

The controversy over his medal rumbled on, over the years, the Truro Daily News published several articles highlighting Jones' heroics on the battlefield and his recommendation for the DCM. A letter from a Truro soldier based in Witley Camp, Surrey, England on 29 July, 1917, that was published in the Truro Daily News, quoted the writer as saying, Jones, "had captured a German machine gun, forced the crew to carry it back to our lines, and, depositing it at the feet of the CO. said;- 'Is this thing any good?'" On 21 September, 1917, Jones's sister Martha told The Truro Daily News that Jones "won the DCM by capturing a German machine gun and crew". The newspaper once again alluded to the medal recommendation, in an article on Jerry's 79th birthday. This time they reported "His valor won for him a recommendation for the DCM". The problem was that there was no official recognition of the medal.

Jeremiah Jones died in 1950. His cause was taken up by Calvin Ruck , a Human Rights activist who held a number of positions within the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and organized campaigns against businesses in the Dartmouth area, including barber shops, which refused to serve black people. He worked with the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission from 1981 to 1986. He later became a Canadian senator. Throughout most of his life he campaigned tirelessly for the Canadian Government to recognize the heroics of Jeremiah Jones.

Finally ,on February 22, 2010, sixty days after his death the Canadian Government recognized Jones posthumously with the awarding of the Canadian Forces Medallion for Distinguished Service.. At a ceremony held at the Royal Canadian Legion Branch in Truro, Rear Admiral Paul Maddison, Commander JTFA and MARLANT, presented the medal to the Jones family on behalf of the CF and DND. “Pte Jones was a proud African Nova Scotian and a military hero,” stated Maddison. Calling the medallion “an award for valour second only to the Victoria Cross,” Maddison noted that after a long delay in acknowledging Pte Jones’s actions during the First World War, “We are finally able to formally honour him.” Better late than never.

Jeremiah Jones was certainly not the only black Canadian to pass through Buxton. In February & March 1918. Sapper Miles Dymond, also passed through the Canadian Discharge Centre . Miles Smith Dymond was born in Fredericton, New Brunswick in 1882. He was working as a stone cutter in when he enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force at Valcartier on 23 September 1914. He was an active militia member of the 1st (Brighton) Field Company of the Canadian Engineers. Myles was amongst one of the first Canadians to volunteer for CEF service. Sapper Dymond went to war leaving behind his pregnant wife Ada Ray and his 1-year old son Myles Smith Dymond, Jr, his 4-year-old daughter Inez and six year old daughter Thea. . Myles, and his unit, were part of the 1st Canadian Contingent that sailed for England on 4 October 1914. He was posted to 17th Field Company of 1st Canadian Divisional Engineers to be employed where the greatest need was required. As a stone cutter/mason his skills would be useful in repairing damaged bridges and in repairing and/or constructing wells to ensure water supply for the division. Myles arrived in France on 18 March 1915. In time for the second battle of Ypres. French North African units that bolted in panic during the first gas attack of the western front – leaving a three kilometre gap in the trenches and the Canadians held that gap for three days until relieved by the British. In July 1917 Myles, having survived the battles in the Somme Valley and the battle of Vimy Ridge, was posted to 3rd Field Company, CE, 1st Canadian Divisional Engineers. After taking part in the battle of Hill 70 his unit moved north to enter into the ongoing slaughter of the Battle of Passchendaele in Belgium. His work on bridge sites was hazardous as those work sites were easy targets for German long-range artillery and German bombers. On at least 3 occasions Sapper Dymond Dymond was buried as a result of very close artillery strikes. Nonetheless, he did survive but the harsh conditions of rain, flooding, mud and foul weather were taking a toll on the 36-year-old father of three. On 19 February 1918 Myles was evacuated back to England and invalided home to Canada a week later due to poor health.His service records state that he passed briefly through the CDD in Buxton

Both Jones and Dymond were unusual in having served in unsegregated Canadian Units A large number of Black Canadians served with the number 2 Construction Battalion. On 11 May, 1916, the War Office informed the governor general that it approved of the formation of this unit. So on 5 July , 1916, No. 2 Construction Battalion was authorized. Its headquarters was initially in Pictou, Nova Scotia, but moved to Truro, Nova Scotia, in September 1916. The original intention was to recruit the unit primarily from Canada's Maritime Provinces, with companies also being raised in Ontario and Western Canada. A little over a month after the unit was authorized, however, only 180 recruits had been obtained. the battalion did manage to obtain about 165 men from the United States. When the men were finally assembled in March 1917 to prepare for departure overseas, the battalion's overall strength was just over 729 men. During their deployment, new troops of other nationalities, including 150 Russians, were attached to the unit. Although a Black unit, all but one of the unit's 19 officers were white, the exception being Captain William A. White, the unit's chaplain. The unit departed from Halifax, Nova Scotia, on board the SS Southland on 28 March , 1917 and arrived at Liverpool, , ten days later. Lacking the numbers to make up a battalion, the unit was reorganized as No. 2 Construction Company in May 1917, and attached to the Canadian Forestry Corps By Autumn 1917, the unit was operating in the Jura Mountains of France, headquartered at La Joux . In conjunction with the CFC, troops of the No. 2 Construction Company axed down the trees of surrounding forests, transported the logs to mills, and milled them into lumber to be used on the front by Allied armies. Horses, trucks, and trains were used to transport the logs. The No. 2 Construction Company was responsible for handling and caring for the 70-100 horses. It drove the trucks and maintained the roads. It built a railroad and occasionally operated the trains. It was also responsible for operating and maintaining utilities for CFC camps, such as water pumps and an electrical power plant. All this work was done despite terrible weather conditions and frequent outbreaks of disease. The men of No. 2 Construction Company returned to Canada in early 1919 and the unit officially disbanded on 15 September of the same year.

On 9 July, 2022 the then Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau offered an apology as descendants of the No. 2 Construction battalion’s 600 members gathered in Truro, N.S., on the same grounds where the unit formed prior to deployment overseas in March 1917. Trudeau said he was there to apologize for the appalling way the patriots were treated, saying:

“As a country, we failed to recognize their contributions for what they were — their backbreaking work, their sacrifice, their willingness to put their country before their self,”

Trudeau then told the crowd:

“For the overt racism of turning Black volunteers away to sacrifice their lives for all — we are sorry. For not letting Black service members fight alongside their white compatriots, for denying members of the No. 2 Construction Battalion the care and support they deserved — we are sorry. For failing to honour and commemorate the contribution of No. 2 Construction Battalion and their descendants, for the blatant anti-Black hate and racism that denied these men dignity in life and death – we are sorry.”

Apart from Jeremiah Jones and Miles Dymond , it is entirely possible that men of the Number 2 Construction Company passed through Buxton. If I find any names, I will update accordingly.

Service Records at Canada Archives

JONES, JEREMIAH JERRY (3 digital object(s)) Genealogy / Military / First World War Personnel Records

DYMOND, MILES SMITH (3 digital object(s)) Genealogy / Military / First World War Personnel Records

On the award of the DCM to Jeremiah Jones

From Trident , the Journal of Maritime Forces Atlantic, VOLUME 44, ISSUE 5 • MONDAY, MARCH 8, 2010Wayback Machine

Additional information on Miles Dymond from the site www.blackcanadianvetrans.com which also contains the stories of many veterans of Number 2 Construction Company

Black History | Black Canadian Veterans Storiesù

Number 2 Construction company

Calvin Ruck's book is available to borrow at Internet Archive

Justin Trudeau's apology to the descendants of men of the number2 Construction company