The destruction of Milan- eighty years on

Usually my articles end up not exactly coinciding with the events they are supposed to commemorate. Since this covers a period of several weeks on this occasion I am more or less on time.

Eighty years ago , in a series of raids in July and August 1943. The Royal Air Force more or less destroyed the historic centre of Milan, together with most of the city’s infrastructure , transportation, and a large proportion of its housing stock, not to mention a large part of its artistic patrimony. The Italians did a fine job of putting the city back together again, if you visit today, it is not entirely clear which bits were destroyed In fact some of the ugliest bits of Milan are pre-war and seemed to have escaped more or less unscathed. Milan was by no means Hamburg, Dresden , Coventry, London, or Tokyo, but it still suffered. In the bombing of August 1943, an estimated 1033 Milanese lost their lives, in addition to around 50 or so, British and Commonwealth aircrew. The city got rebuilt, the lives were lost forever. At the time of the British blitz on Milan , Mussolini had been deposed by the Fascist Grand Council and was in prison ( he had yet to be freed by the Germans ), Sicily had been invaded and the Italians were putting out various peace feelers to whoever would listen. British policy appears to have been to give them an extra nudge to the negotiating table by trying to raze Italy’s second largest city to the ground. While the Americans might have bombed Milan later in the war, August 1943 was a British Enterprise. The British had bombed Milan, before notably in October 1942 when they had done considerable damage but, on that occasion, they had come during the daytime and attacked mainly industrial targets. In 1943, the British and Americans had both managed to avoid destroying the cultural patrimony of Rome and Florence, while bombing quite precisely railheads and military targets. In Milan, as they did in German cities the British decided to go for area bombing , which in Milan’s case meant destroying the historic centre. The British had suffered the Blitz at the hands of the Germans and the Baedeker raids on historic British cites , a few Italians had been involved in haplessly bombing Ipswich , but the destruction of Milan was rather more than a quid pro quo for Ipswich. Maybe the Italians had bought it on themselves by stabbing in the back their former WW1 Allies Britain and France by declaring war on both when they were in an existential struggle with the Germans. And the Italians had proved in attacks on Barcelona and on Tel Aviv that they were not adverse to indiscriminate civilian bombing. But for all of that , the destruction of Milan seems to have been militarily useless, and even counterproductive for the propaganda value it gave to the Germans and their puppet Mussolini regime of the RSI.

In August 1943, the Italians were already well beaten, instead of letting them be counted out , the British extended them a severe kicking while they were bloodied and on the canvas.

The irony is that the principal theorist of strategic bombing was an Italian, Giulio Douhet. In his book “the Command of the Air”, Douhet argued that air power was revolutionary. Aircraft could fly over surface forces, relegating them to secondary importance and the vastness of the sky made defence almost impossible, so the essence of air power was the offensive. An air force that could achieve command of the air by bombing the enemy air arm into extinction and then condemning that enemy to perpetual bombardment. Command of the air meant victory. Douhet believed that area bombing could break a people's will by destroying a country's "vital centres. His model rested on the belief that in a conflict, inflicting unacceptable costs from aerial bombing would shatter civilian morale and pressure citizens into asking their governments to surrender. Douhet argued the war would become so terrible that the common people would rise against their government, overthrow it with revolution, then sue for peace. .As soon as one side lost command of the air it would capitulate rather than face the terrors of air attack. In other words, the enemy air force was the primary target. A decisive victory from the air would hasten the end of the war. Which is pretty much what the British decided to try on he stricken Italians.

After the British raids in October 1942, there was a lull until Milan suffered a new bombing on the night of 14/15 February 1943. 142 Lancasters dropped 110 tons of explosive bombs and 166 tons of incendiary bombs over the city. Several factories were damaged, including Alfa Romeo at Portello ( in the North of the city) , Caproni at Taliedo ( near to today’s Linate Airport), Isotta Fraschini ( no longer making Luxury Cars but rather more prosaically aero -engines and Breda in Sesto San Giovanni. At the time , all of these were producing aero-engines, planes, military tricks and weapons which were keeping the Axis war machine going. Coincidentally the RAF was well aware of these locations, since up until a few months before the Italians had declared war on the French and British, they had been in serious negotiations to but planes and engines from Caproni and Isotta. So they well knew the locations. Milano Centrale railway station and the Farini marshalling yard were also hit, Milano Centrale was the hub of communications for passenger trains, with the huge Farini yard performing a similar function for freight traffic. All of these were on the periphery and suitably far removed from the centre of the city. Residential areas were also badly damaged, with 203 houses destroyed, 596 heavily damaged and over 3,000 slightly damaged. This raid damaged the headquarters of the Milanese newspaper the Corriere della Sera , the Palazzo Reale near the Duomo, the The Teatro Lirico, and the Basilica of San Lorenzo. To extinguish the fires, it was necessary to call firefighters from neighbouring provinces and even from Bologna. 133 people were killed in the attack, 442 were wounded and over 10,000 were left homeless. Schools had to close down, and more citizens evacuated the city. The only RAF loss was one Lancaster shot down.

Although the February raid was highly destructive, at the time Mussolini was still in power and the Italians were still fighting alongside the Germans in North Africa. It has been suggested that the timing was designed to coincide with the widespread surrender of Italian Forces in North Africa and Stalingrad, as an extra moral damaging exercise. Milan was not bombed again for six months but at the beginning of August 1943, following the fall of Mussolini, it was decided to start a series of heavy bombings on the main Italian cities, to persuade the successor government of Marshal Badoglio to surrender.

The night of 7/8 August

On the night of 7/8 August 1943, 197 bombers took off from bases in England to carry out a simultaneous bombing of Milan, Turin, and Genoa. Milan was bombed by 72 aircraft which dropped 201 tons of bombs, mainly incendiaries. 10 Lancasters of No 61 Squadron RAF took off from RAF Systerton from 21.00 onwards, around 4 hours later they were over the target and dropping bombs. Only nine out of ten aircraft made it back- Lancaster LM339 was lost over the Alps. It assumed to have crashed into Monte Rosa and the crew all killed. The crew were buried at Issime in Val d’Aosta. After the war, they were reinterred at the CWGC Cemetery in Milan . of the seven man crew, six were British RAF PO H Halkier, Captain (Pilot) RAF Sgt C P Southcott, (Flight Engineer) RAF Sgt D W Thirsk, (Navigator) RAF FO Filmer, E (Air Bomber) RAF Sgt F E West, (Wireless Air Gunner) RAF Sgt D Brown, (Mid Upper Gunner) , the final man 417006 Flt Sgt, Edmond Rhys Smart (Rear Gunner) was an Australian from the Royal Australian Air Force attached to 61 Squadron.

Pilot Officer Halkier killed as his plane returned from a raid on Milan on 7/8 August 1943. CWGC Cemetery Milan

Ten Lancasters from No 619 Squadron RAF took off from RAF Woodhall Spa in Lincolnshire. Lancasters between 21.00 and 21.15, The squadron had bombed Hamburg on 2/3 August and then spent the next days in training and exercises. On 7 August they were ordered to join the attack on Milan. They reached Milan in clear conditions around 1,15 in the morning dropping bomb loads from 16 ,000 and 17,000 feet at targets identified by green TI fares. The operations summary reported that

“ All aircraft reached target area. The weather conditions were good , crews reporting fires very concentrated, F/L Jones Inner port engine caught fire on way back and had to be feathered “

The normal route from Yorkshire and Lincolnshire was across the channel coat in Normandy then south of the Paris area and down through eastern France ,. Lake Bourget and Annecy where a beacon indicated the way. Here the bombers turned to cross the alps in the area of Bardonecchia – before heading eastwards through the Val d’Aosta in the direction of Turin/ Genoa or east towards Milan. Although it lengthened the route, great care had to be taken not to violate the airspace of neutral Switzerland. It happened on occasions drawing the fire of Swiss Anti- Aircraft gunners and Swiss diplomatic protests to London.

The bombers were guided by other Lancasters from the Pathfinder Force. No 97 Squadron RAF was based at RAF Bourn in Cambridgeshire, on 7 August seven Lancasters left from there to guide the rest of the bombing force to Milan., leaving between 21.27 and 21.36- From the Operational Records the planes and crews involved were:

JA916L W/C K.H. Burns, P/O E.G. Dolby, P/O J.E. McAvoy, P/O Keddie, F/Sgt R.J. Williams, F/Sgt E.H. Skinner, F/Sgt Lambert. Up 2127 Down 0508. Primary objective Milan attacked. 10,000’. No cloud. Visibility good. Target identified visually in light of flares and red TI markers. Bombed on red TI marker. Fires from incendiaries seen developing as aircraft left target area.

JA857C S/L E.E. Rodley, Sgt J.E. Bell, S/L K.J. Foster, F/O L.S. Webb, Sgts C.T. Ambrose, A.J. Croll, F/L R.A. McKinna. Up 2129 Down 0528. Target Milan successfully attacked from 12,500’. No moon. Visibility good. Target identified visually and red TI. Bombed big building in bomb sight, near isolated red TI. Big red explosion seen immediately after bombing. Good concentration of fires – visible about 80 miles away.

JA908N F/L J.H. Sauvage, Sgt W.G. Waller, F/O H.A. Hitchcock, F/O F.P. Burbridge, F/Sgt E. Wheeler, F/O J.E.Blair, Sgt G.W .Wood. Up 2131 Down 0521. Milan attacked. No moon. No cloud. Visibility good. 12,000’. Bombed on centre of concentration of red and green TIs, overshot 4 seconds. Fires average, rather scattered. One column of smoke up to about 5,000’.

JA846E ( Crew F/L A. Eaton-Clarke, Sgt G.S.Dunning, W/C R.C.Alabaster, P/O A.N.Carlton, F/Sgt G.K.Smith, Sgts E.Hambling, P.A.Walder. Up 2134 Down 0536.) Primary target Milan bombed. 13,500’. No cloud. Visibility good. Red TI markers in bomb sight when bombs released. One very large explosion seen at 0125. Good fires raging as aircraft left target.

ED938J ( Crew F/O J.F.Munro, F/O W.Riches (2nd Pilot), P/O R.C.Swetman, P/O A.H.G.Spencer, P/O E.J.Suswain, Sgts J.Wrigley, K.S.Bennett, F/Sgt W.Hill. Up 2136 Down 0524.) Target Milan attacked. Visibility good except for smoke haze. 11,500’. Single red TI marker in bomb sight at time of bombing. Seven good fires seen increasing north of aiming point. Glow seen from Alps on return journey

Target indicators, ( TI's), were flares dropped by Pathfinders onto the target, providing an easily seen visual aiming point for the following "main force" of bombers to aim at. After their introduction, the use of TIs expanded to include en-route markers to gather up lost aircraft, additional TI drops to keep the target lit over long periods, and various changes in technique to address German defences. The use of TIs allowed the RAF to concentrate its advanced navigational systems in the Pathfinder units. Most widely used were the H2S ground scanning radar and Oboe navigation system, the former requiring considerable training to be useful, the latter able to guide only a single aircraft at a time. The limited number of navigational units meant that spreading them through the force would have limited effects. By concentrating these in a single Group (No. 8 Group RAF) and having them drop TIs, the accurate fixes could be used to guide the entire attack. Target indicators were available in various colours, some with ejecting stars of the same or a different colour. During a raid, bomb aimers would be instructed by the Master Bomber to drop their bombs on the target indicators of a specified colour, the marker aircraft carrying different colours to be used if the initial target indicators were dropped off-target. The first target indicators could be cancelled over the radio by the Master Bomber and the marker crews instructed to drop new target indicators of a different colour, until the correct aiming point was correctly marked. The Main Force bombers would then be instructed by the Master Bomber to bomb the colour of the most accurate target indicators. In that raid large parts of the city centre were set ablaze; 600 buildings were destroyed, with 161 victims and 281 wounded among the population.

In the raid large parts of the city centre were set ablaze; 600 buildings were destroyed, with 161 victims and 281 wounded among the population. The only factory that was damaged was the Pirelli plant. The headquarters of the Corriere della Sera were hit again and partly destroyed.

The offices and printing plant of the Corriere della Sera in via Solferino

The newspaper reported on the raid on 9 August with the headline “Il bombardamento terroristico di Milano” .

The report started by stressing the non- military nature of most of the targets which including, housing, churches hospitals and historic monuments. It also reported that two British planes had been bought down by antiaircraft fire. One had crashed in the area of via Gustavo Modena. Al the crew had been recovered and taken for burial , another plane had come don in fragments in the area of viale Campania – via Compagnoli, also hit by anti-aircraft fire. This is curious, since apparently the only crew buried in the Milan Cemetery from that date were the crew of 61 Squadron apparently bought down over Monte Rosa and later buried in Milan after the war. British records indicate only two losses for the raid, including a plane from 106 Squadron shot down over France. Neither the Runnymede Memorial or the IBCC database record any likely candidates for the crew of those two planes. It seems strange that especially in the largely populated via Gustavo, that the pate would have invented a crash- On the other hand it does not fit with the British records.

The paper continued its reporting on the theme that bombers had dropped many heavy calibre bombs and incendiaries at random and away from military targets .A large calibre bomb had hit the Ospedale Fatabenefratelli causing severe damage, but without claiming lives and the hospital patients had been moved elsewhere. The Church of Santa Croce all’Acquabella in via Sidoli (to the east off the city) ) and the synagogue in via Guastalla closer to the centre) had also ben hit . La Scala had taken incendiary fragments on the roof while the nearby Teatro Filodrammatico had caught fire.

Targets were well spaced out including the Biblioteca Braidense within the Palazzo Brera. The Pinacoteca di Brera was also hit in this raid.

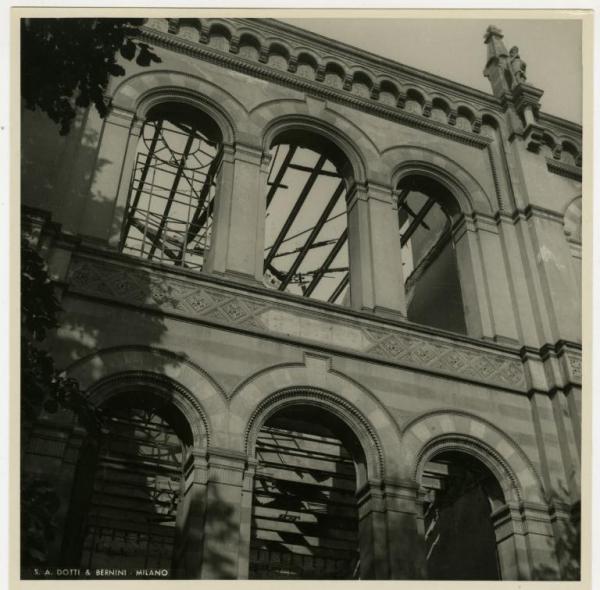

The Palazzo Brera was hit by the bombing of 7/8 August. Fortunately most of its collection had been removed to safety

As soon as the war broke out, on 10 June 1940, the museum had transferred its most important works to safer buildings in protected locations. In Milan, the armoured room, the so-called "sacristy", of the Milan headquarters of the Cassa di Risparmio delle Province Lombarde and the basements of the Castello Sforzesco were identified as highly secure. Artworks were sheltered as far away as Perugia.

On 8 August 1943, a large calibre explosive bomb exploded on the building opposite the Pinacoteca, fifteen incendiary bombs and about two hundred and fifty incendiary fragments fell on the building, hitting all the rooms of the gallery that overlooked via Brera, the square and the botanical garden. Severely damaged was the Napoleonic Room. Parts of the roof and vaults collapsed, and the perimeter walls became unsafe. The statue of Napoleon Bonaparte in the centre of the courtyard of honour, had been caged and protected by sandbags and was not damaged.

Napoleon survived the war surrounded by sandbags

The former director of the Brera Ettore Modigliani had been fired from the Museum in November 1938 under Italy’s Racial Laws. Exiled in the Marche, and technically unable to write for the Press, he nevertheless managed to publish in the “Il Giornale” of12 August 1943, a scathing attack on the British bombardment of Milan.

[...] You ruthlessly bomb and burn our most illustrious, historic and monumental cities, also because we are unable to answer you, if we wanted to. It is - it is said - the law of war, and up to a certain point it may be true if they take the motives of so-called military objectives at face value.

[...] your airmen - on command received - are no longer concerned with military objectives but aim to strike (the "war of nerves"!) the very central districts of our cities, knowing full well how it is inevitable that, in such conditions, bombs and fragments injure or destroy historic-artistic monuments among the noblest in the world. Do you realize this? Think towards the future and ask yourself: what will happen in the near or distant future? Don't you really care about the consequences? Knowing that your name can be eternally cursed, not by us alone, but by your own descendants… […]

A few km away and further to the east. , the area around the Giardini Pubblici was badly hit . Muirhead’s’ Guide to Northern Italy (1924) describes the area, before the war.

“ At the end of the street on the left , are the Public Gardens an artistically laid out park with several Public monuments. Facing the Corso is the Natural History Museum .. The ground floor contains mineralogical and palaeontological collections, molluscs, insects and Italian Alpine Fauna; the first floor contains the fish, reptiles, birds and mammals, In the via Palestro , Sooth off the Park, is the Villa Reale (1790) ,once occupied by the regent Eugène Beauharnais , and now containing the Gallery of Modern Art , with paintings by Hayez, Segantini, and other artists , especially of the Lombard School”

At the. Natural History Museum, fire caused by incendiary bombs caused considerable damage to the building and destroyed several important collections, including the botanical and herpetological collection of Giorgio Jan, an early 19th Century expert on snake as well as parts of the palaeontological collection. The Museum did not reopen to the public until 1952.

Bomb damage to the Natural History Museum in the Giardini Pubblici, Milano

The Natural History Museum in Milan un rather better condition today

The nearby Planetarium/observatory was also damaged. Bombs fell within the park, which at the time contained a small Zoological Gardens which was hit in several places.

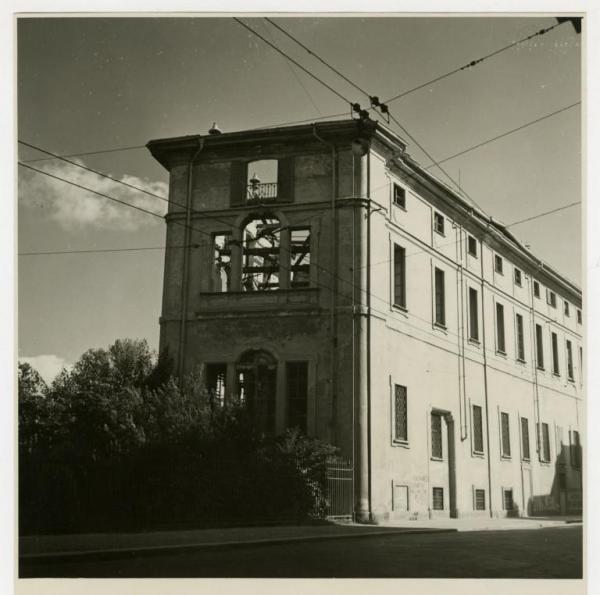

Across the park, the Villa Belgiojoso Bonaparte ( also known as the Villa Reale) was damaged. The villa was la built between 1790 and 1796 by the architect Leopoldo Pollack, commissioned by Count Ludovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso. is one of the main monuments of Milanese neoclassicism. Among the neoclassical works in the Villa were those by Luigi Acquisti and Antonio Canova. The villa became the permanent residence of Eugene de Beauharnais, adopted son of Napoleon and Viceroy. The Viceroy commissioned the sumptuous decoration of the interiors of the noble floor, involving, among others, Andrea Appiani. Bonaparte himself stayed there on his visits to Milan. With the return of the Austrian government to the city in 1814, the building became the property of the Austrian Viceroys, notably Marshal Josef Radetzky. After Independence it went to the Savoy Crown, who donated it to city of Milan. Fortunately the main villa was not hit by the bombs exploding all around but an an entire stable block fronting on via Palestro was destroyed.

The Villa Reale Milano

Bomb damage in the grounds of the Villa

Fortunately the main villa was not hit but stable blocks and outbuildings were destroyed

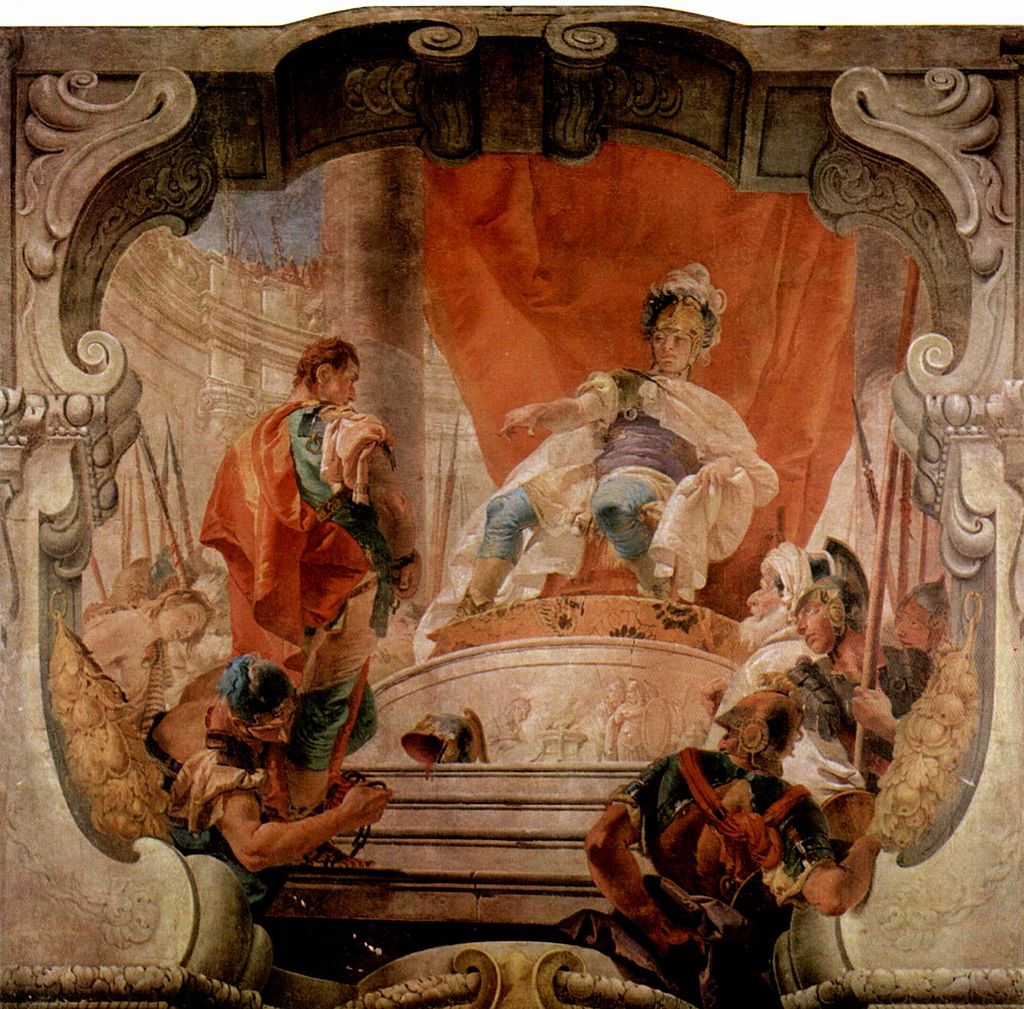

On the far side of the park, the Palazzo Dugnani site of the Civica Scuola Femminile Alessandro Manzoni was badly damaged. The palace was built in the seventeenth century as a patrician residence. In 1753 it was purchased by the Casati family and then Dugnani, an illustrious Milanese family and became the site of grandiose social parties and a meeting place for intellectuals. Its interiors were among the most sumptuous of Baroque Milan: on the walls and ceilings there are large frescoes by Ferdinando Porta . On the ceiling of the Ballroom on the first floor was a grandiose painting by Teatro alla Scala where mythological figures narrated the events of Scipione and Massinissa. Most of these frescoes were removed in 1944 perhaps a little too late in the day and then restored to their original positions in the palace.

Palazzo Dugnani

Palazzo Dugnani after the bombing

Tiepolo's fresco- Palazzo Dugnani

After this raid, public transport was no longer possible in the city centre, as most of the streets were obstructed by ruins or craters, trams and buses had been destroyed or badly damaged in their depots or on the streets, the damaged ones had to be cannibalised to providing working parts for others. Surviving trolley buses could no longer operate, since the overhead cables which provided their power had been bought down. Even when power was restored, public transport remained disrupted.

The night of 12/13 August

On the night of 12/13 August, RAF Bomber Command returned with its heaviest raid on Milan and any Italian city. 504 bombers (321 Lancasters and 183 Halifaxes) took off from England, 478 of them reached Milan and dropped 1,252 tons of bombs (670 explosive bombs and 582 incendiary bombs), including 245 4,000-lb blockbusters and 380,000 incendiary devices, over the city.

If the ground war in Italy was a truly multinational event, the air war was also to become so. Over 150 men from the Royal Canadian Air Force were involved. No 434 Squadron of the RCAF Royal Canadian Air Force ( RCAF) was at in Yorkshire. Between 21.15 and 21.30 , their ten Halifax bombers took off and headed south on a mission to bomb Milan. Each bomber had a crew of seven (Pilot, Navigator, Flight Engineer , Bomber and three Air gunners) On the run-down through France, they encountered some light flak in the Paris area .Crews reported back, that the raid seemed to be successful, although some bombs failed to go off. One plane had to turn back with technical difficulties, the other nine made it to Milan and back with no casualties being suffered,

A little further north at RAF Middleton St George in County Durham , 13 Halifax Bombers of No 428 Squadron RCAF left at the slightly early time of 20,50. The planes reached their targets in the Milan area around 1,24 in the morning , visibility was reported as being good as they launched the bombs from 20,000 feet. The crews described concentrated fires in the centre of town, with some isolated fires elsewhere. Their aiming was been assisted by the use of Green TI flares. Anti-aircraft defences in Milan were reported as being very weak. All planes made ii back safely arriving back safely between 6.30 and 6.50 in the morning .Some were forced to land further south in England to refuel before heading home.

Twenty-two Handley Page Halifax bombers of No 77 Squadron RAF left RAF Elvington in Yorkshire between 20.43 and 21,15 on 12 August Their outline route was to head for Selsey Bill, cross the French coast near Cabourg and then down to Lake Bourget. Five of the planes were carrying 1000lb bombs with various delayed timings, in addition to 4lb and 30lb incendiary bombs. The rest of the planes carried normal 1000lb bombs, plus incendiaries . The 4 lb (1.8 kg) incendiary bomb, developed by ICI, was the standard light incendiary bomb used by RAF Bomber Command, consisting of a hollow body of aluminium-magnesium alloy with a cast iron/steel nose and filled with thermite incendiary pellets. It was capable of burning for up to ten minutes. It was normal for a proportion of high explosive bombs to be dropped during incendiary attacks in order to expose combustible material and to fill the streets with craters and rubble, hindering rescue services. So the large 1,000 lb bombs were designed for the structural destruction and the smaller incendiaries to start fires afterwards. ( if you want to know more about incendiary bombs – further details can be fund here)

On reaching Lake Bourget the bombers were guided in by green route marking flares and then Green Target Indicators over Milan. The bombs were dropped around 1.15 .It was reported that

“ Whole target area covered in good red fires glow seen 80 miles after leaving target area “,

Seven men from 77 Squadron did not make it back again, Handley Page Halifax II(JD125) , was shot down in its way to Milan at around 23.17 near Verneuil sue Avre, in Northern France on 13 August by an FW190 of Lt Detlef Grossfuss of II/JG2 . In the operations reports , a number of aircraft reported seeing a four-engine aircraft shot down over northern France at the same time variously between 23.09 and 23,20 . The reports speak of Air/Air Tracers being seen and also heavy flak in the area . Possibly two planes went down in the same area, The whole crew of jD125 was killed .The summary reports of the raid indicated that over the Target area (Milan)

“searchlights were in effective and not numerous, also flak was only slight heavy”

Other reports indicate the same for the Milan area, and it was only over France that really heavy flak was experienced. A Halifax (JD 234), came under attack by what they believed to an ME110 in the area of Orleans, there was an exchange of fire and the ME110 broke off it attack. Over Milan there was little the Italians could do, Halifax ( JD302) reported a brief encounter with an Italian Breda 88 fighter with which it exchanged fire. The aircraft broke off is attack, Reports also speak of encountering a lone Italian CR42 over Milan. Having reached the maximum of their fuel load in getting to Milan and back , most of the returning bombers had to land in the South of England first – at RAF Hartford bridge in Hampshire, RAF Thorney Island in Sussex and at RAF Tangmere , Ford and Odiham. They need refuelling before that could back to RAF Elvington

A further twelve bombers from 619 Squadron left Woodhall Spa and returned to Milan on 12 August,

“All aircraft successfully reached the target . The weather over the target area was good , there being no cloud and good visibility and ground detail “

Only , eleven bombers returned. One Lancaster suffered a collision over the English coast and unable to find anywhere to land was forced to ditch into the sea. One crew member was lost, with the others subsequently being picked up by a rescue launch . Another crew member subsequently died in hospital.

This raid included No 7 Squadron ,No 166 Squadron and No, 619 Squadron-Again they were guided in by 97 Squadron. From 97 Squadron, one Lancaster crew (JA916L) reported ;

"Up 2117 Down 0516. Target Milan attacked. 12,000’. No cloud. Visibility good. Built up area visually identified. Aiming point in bombsight at time of bombing on red TI. Fires well concentrated and visible 70 miles away. "

On a hot summer night, the bombing caused massive fires in many parts of Milan; as small fires drew air from the surrounding countryside, creating winds that reached a speed of 50 km/h, an event that usually heralded a firestorm, Fortunately this did not materialize owing to the humidity , helped by the wide city streets, the lack of wood used in construction, the lack of combustible materials in storage ( it being summer at the time) and the type fact that the raid was heavy but not very concentrated.

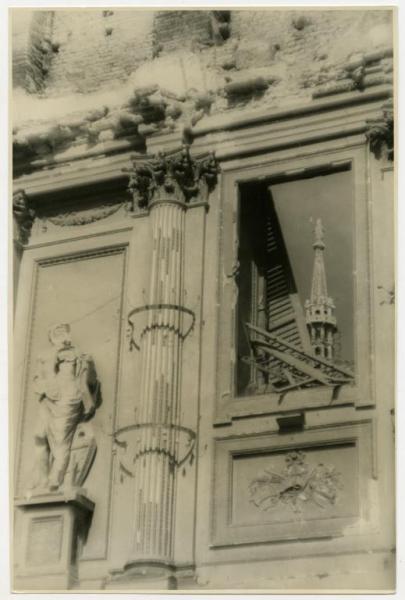

Particularly badly hit was the area around Piazza Duomo The Palazzo Marino and the neighbouring San Fedele Church were badly damaged.

“The Palazzo Marino or town hall , an admirable building by Galeazzo Alessi ( 1558-60) , with a façade by Beltrami (1880)The inner court is picturesque , and in the splendid Sala di Consiglio are frescos by Andrea Semini. The other side of he place faces the Piazza San Fedele, in which are a statue of Manzoni and the church of San Fedele by Tibaldi( 1589) , completed by Martino Bassi,, with a good façade a remarkably designed north side , and a sumptuous interior”

Palazzo Marino

Palazzo Marino was, a sixteenth-century work by the Perugian architect Galeazzo Alessi. Purchased by the State in 1781, it became the headquarters of the municipality of Milan after the Unification . The palace was comparable to some of the richest courts in the West: in the courtyard of the palace were depicted the Labors of Hercules and the Metamorphoses of Ovid. The Hall of Honor (now known as the Salone dell ‘Alessi) had painted on the ceiling the Wedding of Cupid and Psyche in the banquet of the Gods and stuccoes Cupid and Psyche. At the corners of the ceiling Aurelio Busso had painted the Four Seasons. Under the cornice the Muses, Bacchus, Apollo and Mercury frescoed by Ottavio Semino, alternating with bas-reliefs with the stories of Perseus. On the entrances were placed the busts of Mars and Minerva. In 1848, after the Five Days of Milan, the palace became the seat of the Provisional Government of Lombardy. After the liberation of Lombardy from the Austrians in 1859, the palace passed from state property to that of the municipality. On 19 September 1861 Palazzo Marino officially became the seat of the Municipality,

The Hall of Honour, Palazzo Marino before the war

Palazzo Marino after the bombing

Behind Palazzo Marino was the elegant chiesa di San Fedele bult in the 16th Century on the orders of san Carlo Borromeo for the company of Jesus, who had recently arrived in Lombardy. San Fedele was considered a reference model for Counter. Reformation Churches, . The project was entrusted to Pellegrino Tibaldi (an architect who crops up frequently in Milan).At Dan Fedele he was particularly attentive to the reforms of the Council of Trent. Tibaldi’s model included a single nave , emphasizing the importance of the altar. Famously in 1873 the author Manzoni slipped on the steps outside , suffering a trauma from which he never recovered and died shortly after. The bombardment destroyed the Questura of Milan, which at the time was housed in the next-door monastery and severely damaged the church.

San Fedele after the 1943 bombing . The ruined Questura is next door

The chiesa San Fedele and statue of Manzoni

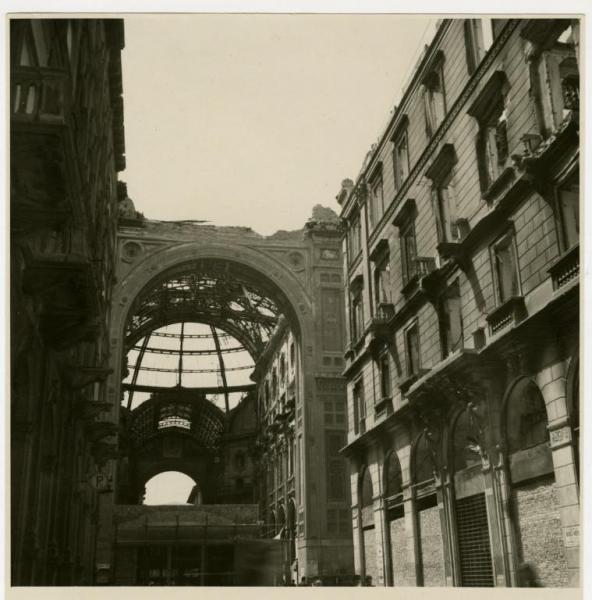

Nearby the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II suffered heavy damage. Somewhat ironically it had been built by a British company. The idea of a street that would connect Piazza Duomo and Piazza della Scala had long been discussed in Milan. The small medieval streets and slum tenements in front of the Duomo were not considered worthy of the city. The viability of the area was tortuous and the narrow streets of medieval origin became less and less manageable with the increase of city traffic. The idea of dedicating this new street to King Vittorio Emanuele II came on the one hand from enthusiasm for a newfound independence from Austria, but on the other hand the city council hoped the name dropping would facilitate the permits for the expropriation of the blocks necessary for the work. The initial municipal guidelines for the project were not for a covered passage, but a simple porticoed street. The Royal decrees arrived: for the buildings to be demolished and to authorize a lottery aimed at collecting the funds necessary for the construction On April 3, 1860 the Municipality of Milan announced the competition for the construction to be evaluated by a specially established commission., 176 designs were selected by the commission and exhibited at the Pinacoteca di Brera the commission did not decree any winner of the competition, but reformulated more precise indications about the project, as a covered passage and announcing a second competition . 18 projects reached the evaluation phase and again no winner was found.

Piazza Duomo

A final competition in 1863 in saw eight projects being evaluated. Giuseppe Mengoni was declared the winner. He had initially planned a single gallery, which was transformed into the actual project of a cross-shaped gallery, The contract for the construction was awarded to the English company City of Milan Improvements Company Limited, The ceremony for the laying of the first stone by King Vittorio Emanuele II took place on March 7, 1865 . The works, excluding the triumphal arch of entrance, were completed in less than three years, a period which was followed by the official inauguration of the Gallery by the king[]. However, in 1869 the contractor company went bankrupt, which forced the municipality to take over the Gallery for the sum of 7.6 million lire. Work finally finished in 1878 when the entrance arch and the northern arcades of Piazza Duomo were completed. Giuseppe Mengoni did see the official inauguration of the complete Gallery: He fell from a scaffolding during an inspection, although according to some rumors it was suicide. The Gallery earned the nickname of "living room of Milan becoming the seat of the bourgeois city life that delighted in frequenting the new elegant shops, but above all the restaurants and cafes: Caffè Campari, the Caffè Savini and the Caffè Biffi. The Gallery was also at the centre of the technological innovations of the time and in its first period it was illuminated with gas then by electric lighting,

The bombing destroyed the glass roof and part of the metal roof, thus damaging the interior decorations. Reconstruction did not begin until 1948 relatively late compared to other symbols of Milan, such as the Teatro alla Scala. Although many proposals had been made that would have modified the construction materials, fortunately the final project was faithful to the original structure. The restoration of the Gallery was completed in 1955; the works were followed by a real second inauguration on 7 December, the feast of the patron saint of Milan.

Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II after the bombs

Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II 2023

Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II 2023

Although not taking any direct hits, the Duomo was damaged by incendiaries.

The Duomo

On the night of the 12/13 . the Archivio do Stato in via Senato was badly hit . Although efforts were being made to move the archives out to the relative safety of Brianza , a large quantity still remained. One of the archive staff, Domenico Alfarone, gave this eyewitness account of the destruction.

Archivio do Stato in via Senato

«The first bomb on the city exploded at 0.10 am on August 13th. You could feel the explosions getting closer; after a very short time, one could hear the whistling of the bombs as they fell . We ran to the shelter and had hardly entered it when a deafening explosion, followed the immense roar of collapse, reached us and shook all our limbs, was we were hit by the blast. Then the lights failed.. When we manged to get on of our lamps lit, we saw the air filled with dense dust and this, mixed with smoke, made breathing difficult. After the first shock, we realized that a bomb of exceptional caliber must have hit the back side of the building; then after a very short interval a second bomb, identical to the first, hit the Palace on the same side, then a third, less powerful, hit on the western side, at the height of the study hall. Other bombs exploded in the woods and one of them a couple of meters from the emergency exit of the refuge.

Meanwhile, fire had broken out, as evidenced by the creaking of the beams and the thick smoke; but we could not realize the extent of the damage: the planes continued to fly over the Palace! Fifty minutes passed before the sirens gave the all-clear signal and those minutes seemed like an eternity; but we, even earlier, when the roar of the aircraft engines seemed to fade, had gone out into the open. The show was creepy! The two monumental courtyards of the Palazzo were strewn with incendiary fragments, many of which were still burning: wreckage and rubble were everywhere. The building, as well as being damaged in its entire rear part, due to the collapse of the large room known as the Debbito publico, which was totally destroyed down to the basement, appeared enveloped by flames in three places: in the rear part overlooking the second courtyard; on the right, entering through the main door, under the portico and, on the left, throughout the first floor: the palaeography school, secretarial office, study room, library, offices, record deposits! The incendiary bombs and shrapnel had started fires in many points and the fire, easily fed by the furniture, ithe wooden shelves and the papers and favoured by a strong wind had spread lightning fast. The flames rose with their tongues beyond the roof for a few meters, sending sinister flashes. The team immediately went to the first floor to try to break into the offices and bring out at least the crates of books arranged along the hallway leading to the offices; but the street was blocked by the rubble and the flames which had invaded the library room. The study hall no longer existed. Flames advanced from right and left, one collapses following another; dangers became imminent. There was nothing more to be done: the Palazzo del Senato was destroyed!!

The courtyard of the Archivio do Stato in via Senato asfter the bombing

An attempt was then made to save at least the rooms located in the centre of the building and which separated the first from the second courtyard; but efforts in this direction had to be abandoned. The hydrants hardly gave a little water: the necessary pressure was lacking. We tried, in vain, to connect to the hydrant outside the building, at the the corner of via San Primo. The 125 mm mouth, purposely implanted, for prevention, remained unused, not having a fire engine available.When it was possible to stop a fire truck, which was passing through via Senato, the fire fighters in front they did not even want to linger at the huge blaze, believing that any intervention was now useless. An attempt was also made to isolate the fire and interrupt the continuity of the tinder in the rooms on the ground floor under the porch (the one already closed in glass), but it had to be abandoned because the flames tried to block the way out and the smoke suffocated . It is perhaps superfluous to say that the fire alarm, in direct communication with the fire brigade command, like the telephones, did not work. All that remained then was to witness the terrifying spectacle in consternation».

The Madonina - symbol of Milan

The Turin newspaper La Stampa described the scenes in Milan

“Milan has suffered a new violent bombing. It can be said that no district, no area, no central or peripheral street in Milan has been exempt from this painful and bloody contribution. The centre has had disfigurements that will remain as evidence of the lack of civilized spirit of our enemies. "

The death toll, although never fully ascertained, was an estimated 700 deaths; casualties were not higher because about 900,000 of the city's 1,150,000 inhabitants had already left after the previous attacks. Most of those who were still in Milan evacuated the city on August 13.Even those who remained tended to leave the city in the evening and head into the countryside on the edges of Milan. At night the city became a ghost town.

The RAF lost three bombers on that raid. It was not just through enemy action. Some nearly made it home. Returning from Milan on 13 August a Lancaster( ED361) of 207 Squadron collided with a 619 Squadron Lancaster (JA844 )crashing near Horsham in Sussex. F/S Kenneth Edward Goodsell, was killed. Goodsell was buried in British soil in Tunbridge Wells-,Other crew members who survived were: Sgt R Cartwright (pilot), Sgt SV Venton, Sgt JM Crawford, Sgt RE Broadbent, Sgt TA Davidson, Sgt E Harman. Two crew on the 619 Squadron plane were killed Sgt’s-David Vincent Jones and Leslie Thomas Christian Maddaford. Both were buried in the UK

The night of 14/15 August

On the night of 14/15 August, fires were still raging when Bomber Command returned with 134 Lancasters (out of 140 which had originally taken off; one was lost), which dropped 415 more tons of bombs. Again the raid was guided by 97 Squadron. Many military-industrial targets were hit (Breda, Pirelli, Innocenti, Isotta Fraschini) and the Farini marshalling yard were badly hit. There was again substantial damage to the historic centre of Milan,

The Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore was severely damaged, as was the nearby Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio. Inaugurated on 7 December, 1921, in the presence of Cardinal Achille Ratti, the future Pope Pius XI, in 1932 the University moved to the historic Cistercian monastery of Sant'Ambrogio designed by Bramante, whose two characteristic cloisters became one of the symbols of the University. The convent, which stretched on the right side of the basilica of Sant'Ambrogio, was built by Benedictine monks in the eighth century and sold in the fifteenth century to Cardinal Ascanio Sforza to the Cistercian monks of Clairvaux. The cardinal ordered the reconstruction of the monastery on a design by Bramante. The project involved a large square with four cloisters, but only two were built: the cloister ion (as close to the church) was built under the direction of Cristoforo Solari until 1513, and the Doric cloister, built in 1620-1630 on Bramante model. Following the suppression of the monasteries in the 17th century , the building was used as a military hospital When it became the seat of Cattolica, Father Gemelli entrusted the restoration Giovanni Muzio (who also designed the Triennale di Milano), who worked for about twenty years, from 1928 to late forties, resuming after the destruction caused by the bombing of 'August 1943.

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore after the 1943 bombing

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore with Sant'Ambrogio in the background

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore-2023

The cloisters of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

The Romanesque style Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio was one of the most ancient churches in Milan, commissioned by St. Ambrose in 379–386, in an area where numerous martyrs of the Roman persecutions had been buried. The first name of the church was in fact Basilica Martyrum. The church assumed its the current appearance in the 12th Century, when it was rebuilt in the Romanesque style. In August 1943, the Allied bombings heavily damaged the basilica, in particular, the apse and surrounding area.

Sant'Ambrogio bombed

Sant'Ambrogio after the bombing

Sant'Ambrogio 2023

In the midst of all that tragedy, the British managed to bomb a hospital housing their own and other Allied Prisoners of War. Seven or eight Commonwealth-PW’s and medical attendants were killed , plus two French prisoners. The British blamed the Italian for moving the PWs to a hospital in war zone, the Italians responded that the British had done the same with Italian PWs in London. The hospital was 500 yards from the Central Station which was a legitimate target. Presumably the British did not know what it was being used for. The Italians did have a pretty poor track record in correctly making and identifying hospital ships or ships carrying PWs. This was just one pf the many hospitals in Milan, that were wholly or partially destroyed n the bombing.

The school in viale Brianza used as a Prisoner of War Hospital

Viale Brianza 2023

Private Tuffley of the New Zealand Medical Corps kiled in the bombing of the hospital. CWGC Cemetery Milan

The night of 15/16 August

On the following night, ( 15/16) 186 Lancasters returned (13 more bombers did not reach the target; 7 were lost, mainly to Luftwaffe fighters on the way back) for a final raid, during which they dropped an additional 601 tons of bombs.

The raid included bombers from

49 squadron- RAF Fiskerton

57 Squadron RAF Scampton

61 Squadron RAF Systerton

207 Squadron – RAF Langar

467 Squadron RAF Bottsford

On the night of the 15/16 , another outpost of the archives was hit at the church of Sant’ Eustorgio, in piazza Sant’ Eustorgio. The archivist Alfarone, also bore witness to that.

«The twelve immense corridors, which developed around the two large courtyards of the cloister, overflowing with deeds and registers placed in very high shelves which covered the walls almost up to the ceiling and also rose along their median line, doubling them in the whole their length, became almost at the same time immense furnaces which devoured everything in a few hours and it is no exaggeration to say that only one sheet of the immense deposit was saved, except for what had previously been removed. Today the unsafe walls that remained standing have been demolished and of the long corridors only the plant remains. The premises that contained the branch of Sant'Eustorgio now seem like the ramparts of a deserted castle!».

In the event , the Archives lost nearly a third of their precious records in those two disastrous days.

The central area was bombed again damaging La Scala theatre and totally destroying La Rinascente department store.

Teatro alla Scala

The Teatro alla Scala was built under a decree of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, at the request of Milanese patrician families, to replace "Regio Ducale", the old Milanese court theatre destroyed by fire in February 1776. The same families undertook to bear the costs for the construction of the new theatre in exchange for the renewal of the ownership of their boxes. The project was entrusted to the famous architect Giuseppe Piermarini, the theatre was built in place of the church of Santa Maria alla Scala, from which it took its name. On 3 August, in the presence of the governor of Milan, Archduke Ferdinand of Habsburg-Este, the 3,000-seat "Nuovo Regio Ducal Teatro alla Scala" was inaugurated with the first performance of Salieri's L'Europa riconosciuta .

The theatre was not only a place of entertainment at the time: the stalls were often intended for dancing, the boxes were used by the owners to receive guests, eat and manage their social life, in the foyer they gambled on roulette, During the spring and summer of 1807 the interior decorations, were renovated according to the neoclassical taste and in 1814, following the demolition of some buildings including the convent of San Giuseppe, the stage was enlarged according to the project of Luigi Canonica.

Niccolò Paganini held violin concerts there . it saw the premiere off Rossini's La gazza ladra and the first works of Giuseppe Verdi , including I Lombardi alla prima crociata and Giovanna d'Arco, After the staging of Joan of Arc, in 1845, Verdi had artistic differences of opinion with the management and left the Scala, he finally returned in 1869 with the success of a renewed version of La forza del destino. Other productions staged by the composer were the success of the European premiere of Aida . the new version by Simon Boccanegra ), the second Italian version in four acts of Don Carlo and the world premieres of Otello and Falstaff

After the First world war there was a radical transformation of the management criteria: thanks to the renunciation of the right of ownership both by the box players and by the Municipality, the Ente Autonomo Teatro alla Scala was founded and the theatre finally enjoyed complete autonomy.. Toscanini was musical director, and the stage of La Scala saw the greatest singers of the time, In 1929 the fascist state reserved to the head of government the faculty of appointment of the president of the institution and Toscanini, having completed the demanding tour in Vienna and Berlin, left the direction of the theatre moved to New York. In 1932, Luigi Lorenzo Secchi designed the "staircases of mirrors" connecting the foyer to the foyer of the boxes, the stage was equipped with bridges and mobile panels, as well as a system that allowed to lower the level, facilitating the loading of the scenes directly from the courtyard. [On December 26, 1938, chorus master Vittore Veneziani left La Scala for exile due to the fascist racial laws. The theatre reported slight damage from the raid that took place on August 8, during which the anti-aircraft protection officers managed to extinguish some incendiary pieces fallen on the roof. On the night between 15 and 16 August an incendiary bomb exploded on the roof causing serious damage to the hall (collapse of the ceiling, destruction of the boxes of the sixth and fifth order of the gallery, and serious damage to the underlying and to the service structures).The stage that was spared only because the metal curtain had been lowered to protect it, "We could only cry" recalls Nicola Benois, set designer of the Theatre, "from the beginning of the war we did shows for soldiers and wounded, from that moment the new great wounded was La Scala". It was decided to rebuild the theatre "as it was and where it was" before the conflict.

La Scala after the bombing

Teatro alla Scala 2023

Rinascente was one of the few major buildings in Milan which was lost for goof ad not rebuilt was the Rinascente Department store the old building was completely destroyed and, in the end, demolished. In 1865 the brothers Luigi e Ferdinando Bocconi opened their first store in Milano for ready to wear clothing They expanded throughout Italy and opened a second store in Milan Italy’s first real department store Aux Villes d'Italie, built after the model of Le Bon Marché in Paris, In 1889 the store moved to a new branch in piazza del Duomo. In 1917 Senatore Borletti took over the activities of the Bocconi brothers and renamed the store Rinascente . Borletti wanted an elegant department store and set about improving the quality of the merchandise, but not raising prices. The aim was bringing luxury to all classes. A few says from the store’s rebirth at Christmas 1918 , it was completely destroyed by fire. And was not to reopen until March 1921, When it did so it had been enlarged and transformed with its own bank , hairdressers , tea rooms and orchestra and a post office. After that unlucky start, this was the version that last twenty-two years until it was razed by British bombs.

Rinascente before the bombing

Rinascente . reborn after the war

The Duomo suffered further consequential damage.

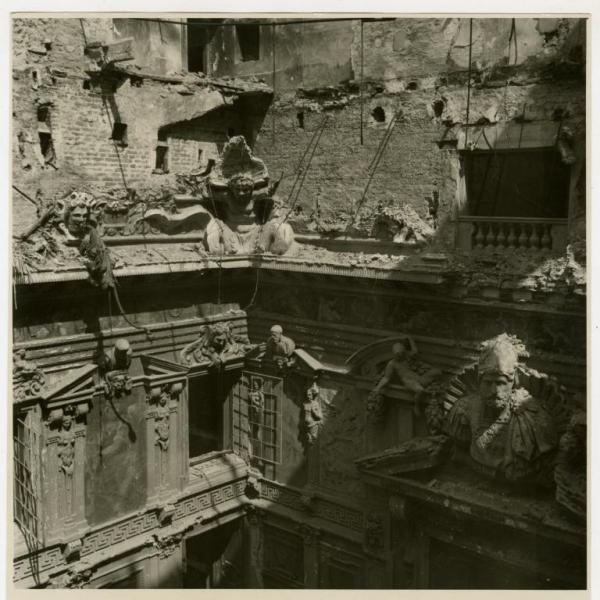

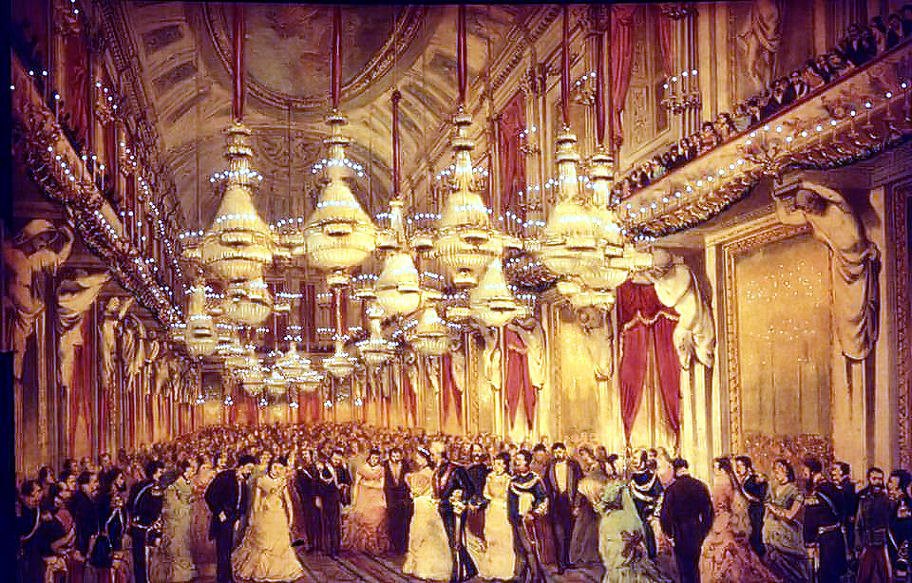

The Hall of Mirrors, of the Palazzo Reale was destroyed. Built between 1774 and 1778 by Giuseppe Piermarini, Giocondo Arbertolli and sculptors Gaetano Callani and Giuseppe Franchi.

The Palazzo Reale

Fortunately there is a pictorial document, which portrays a state ball held in 1875. .In 1919 the King of Italy Vittorio Emanuele III welcomed the President of the United States of America Wilson in the room. The the last official visit held at the Royal Palace, which f became the property of the State of Italy.

The Hall of Mirrors of the Palazzo Reale

On 15 August 1943 a single bomb hit the east wing of the building, but extended, due to air displacements, also to the attics of all the rooms. So also the attic of the Hall of Mirrors caught fire and its combustion caused the collapse of the vault below. The ceiling shattered, collapsing on the marble floor and destroying it.

Bomb damage at the Palazzo Reale

Slightly further away the five hundred year old Ospedale Maggiore were heavily damaged. Fortunately , it had ceased being a hospital at the time, The Ca' Granda, ( the big house) is located between Via Francesco Sforza, Via Laghetto and Via Festa del Perdono.

The Ospedale Maggiore

Designed by the Florentine architect Filarete, it was one of the first Renaissance buildings in Milan The construction of the building began in the second half of the fifteenth century, at the instigation of the Duke of Milan Francesco Sforza, in order to provide the city with a single large hospital for the care of the sick, previously housed in various hospices scattered around the city . It was also good bit of PR by Sforza, who had recently conquered the city and wanted to win the favour of the new subjects with a monumental work of public utility. The first stone was laid on April 12, 1456, . The initial project was conceived by Antonio Averulino known as Filarete, a Tuscan architect summoned to Milan by the Duke on the recommendation of Cosimo de' Medici. The choice of a Tuscan architect, attested Sforza’s desire to equip the city with a building built according to the most advanced construction techniques. In 1465 Filarete left Milan, and the execution was carried out by Guiniforte Solari and starting from 1495 by his pupil and son-in-law Giovanni Antonio Amadeo. They realized the Filarete project with considerable changes to adapt it to late Gothic Lombard tastes. The central body of the building takes its name from the merchant and banker Giovanni Pietro Carcano who, at his death in 1624, left a large part of his wealth to the hospital. Work continued under the direction of the engineer Giovanni Battista Pessina assisted by the architects Francesco Maria Richini, Fabio Mangone and the painter Giovanni Battista Crespi, ". While resuming Filarete’s initial project, the works were modified giving as a final result the current overlap between Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles. Additions continued for years , until bring were completed in 1805. The building continued to perform its function as the major hospital Ospedale Maggiore for Milan until 1939, when the patients were transferred to the new purpose built hospital at Niguarda.

The cloisters of the Ospedale after the bombing

Another view of the bombed out Ospedale Maggiore

Of course, perhaps the luckiest and most celebrated survivor if the bombing was Leonardo da Vinci’s Cenacolo – The Last Supper at the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The Church is located away from the centre of Milan , perhaps the only legitimate target in the area was the Nord Station in piazza Cadorna. Even so it is quite some distance from there. The church was originally built in 1465 and partly rebuilt by Bramante in 1492. , the cloister and the sacristy represented fine examples of Bramante’s work.

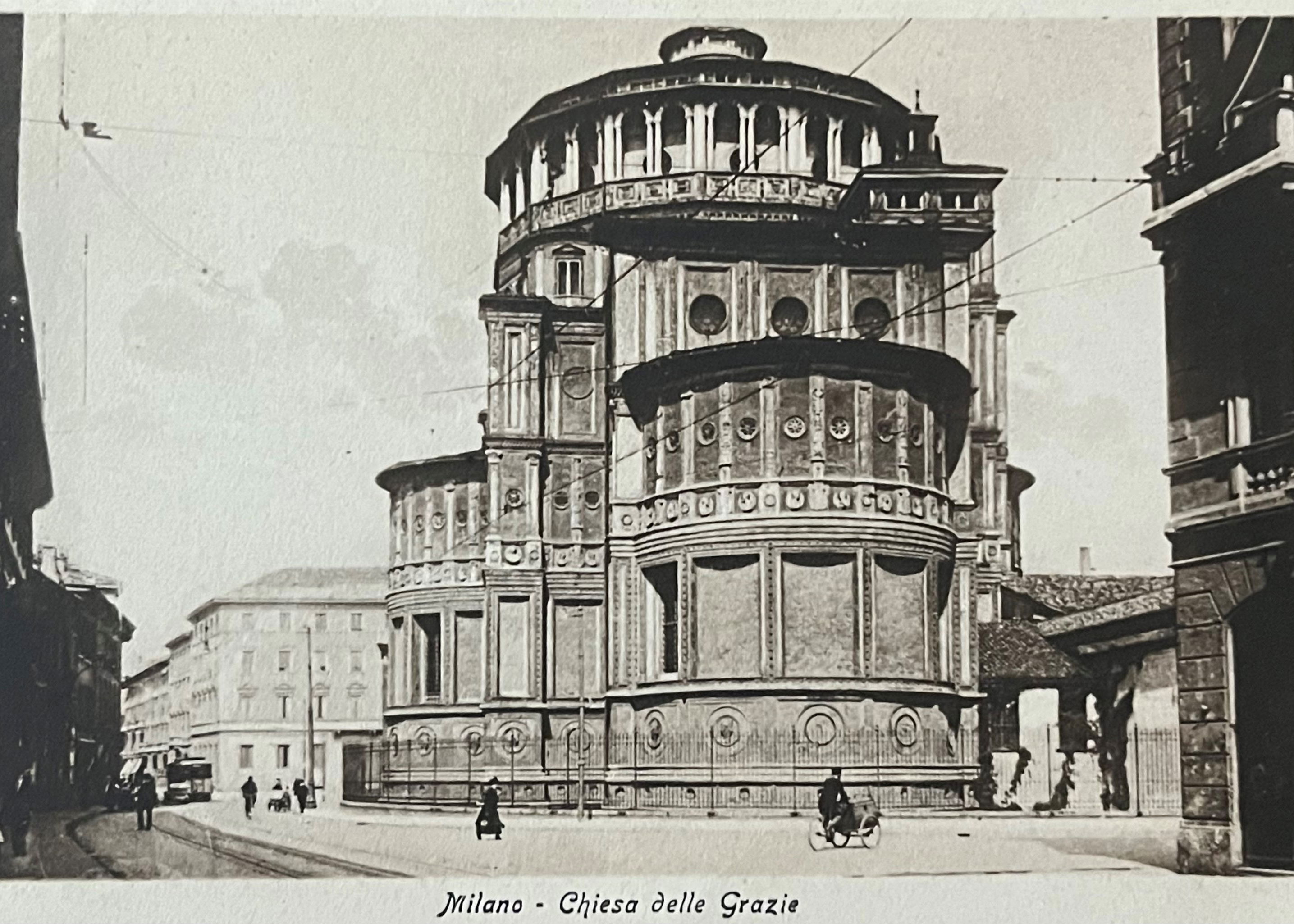

Santa Maria delle Grazie in a prewar postcard

The rear of Santa Maria delle Grazie before the war

Muirhead's Guide offers the following snapshot from the 1920s

“ In the Refectory of the Convent( entrance on the left of the façade : admission 9.30 or 10-4.30 or 5, 2 l ( lire) ; Sundays and holidays, 10 to 1 free) is Leonardo’s world- famous Cenacolo or Last Supper . This is a tempera painting not a true fresco , and the inferior durability of this technique , together with the durability of this technique , together with the dampness of the wall , has caused great damage to the picture , which had, in fact , considerably deteriorated by the middle of the 16th Century. It has been recently restored by L Cavenaghi. In all Italian srt there is no work so profoundly dramatic in character as this painting, which represents the tragic moment when Jesus uttered the words foretelling his betrayal”

Of course, these days you need to book a timed ticket , which are booked out months in advance and costs much more two lire. As mentioned above, the Cenacolo was already in delicate state. Leonardo had tried a few innovative techniques on his fresco, which were less than successful and the painting was already deteriorating in his own lifetime Worse still the wall was exposed to the elements and an underground stream, made it permanently damp , It took a long time to complete and his slowness ( it took him more than two years) irritated the prior of the monastery and his patron, Ludovico who kept asking him to account for his delays. An eyewitness described his creative process.

“ He sometimes stayed there from dawn to sundown, never putting down his brush , forgetting to eat and drink, painting without pause . He would also sometimes remain two , three or four days without touching his brush , although he spent several hours a day standing in front of his work , arms folded , examining and criticising the figures.”

When the fresco was finished in 1498, everyone was amazed. Until then the representations of that subject, from the first frescoes in the catacombs of the fifth and sixth centuries had emphasized the theme of the Eucharist, arranging the twelve apostles around the table while Christ prepared and offered the consecrated bread and wine. The setting of those works was imaginary, the figures were static and devoid of emotion. Often Judas was portrayed to one side, away from Jesus and the other apostles. Leonardo, an attentive observer of nature and a student of the human body, broke with tradition and merged the ceremony of the Eucharist with the dramatic moment in which Christ announces to those present: "Truly I tell you: one of you will betray me". He portrayed the reaction of each apostle to that shocking announcement: Philip brings his hands to his chest as if to protest his innocence, James the Greater he makes a gesture of indignation, Bartholomew does not take his eyes off Jesus and leans forward, while Judas, after accidentally spilling the salt, withdraws defensively and clutches a bag, perhaps containing the thirty pieces of silver. The use of color and the realistic look of the characters involve the observer in Leonardo's dramatic narrative.

Leonardo’s masterpiece was not lucky from the various forces which invaded Italy. In 1620, occupying Spanish troops punched a door right through the painting and in the 1800s, Napoleon's soldiers tied horses to it. Nothing quite like what was to happen to I a hundred and forty years later.

On the night of August 15th, 1943, a bomb landed in the center of the Cloister of the Dead, a small grassy space east of the refectory and north of the church. The explosion destroyed the covered corridor and shattered the east wall of the refectory, collapsing the roof. The girders tearing through the building's fragile vault. Fortunately, in 1940, the officials responsible for the protection of the works of art had placed a protection made of sandbags, wooden scaffolding and metal reinforcements on both sides of the northern wall. Thanks to this precaution, Leonardo's masterpiece did not collapse.

The Cenacolo protected by sandbags

On Sunday, August 15, 1943. Father Acerbi, the prior of the monastery and the brothers had celebrated the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, a subdued celebration owing to the earlier bombing. Acerbi had prayed for the cessation of the bombing, even asking for a few hours of respite: the Milanese were tired and needed to sleep, just like him and the other friars. Shortly after midnight, he heard the dreaded sound of air raid sirens again. Twenty minutes after the sirens, he had heard the roar of bombers, then the first explosions. An almost two-ton device had exploded near the monks' refuge, with a deafening roar. A few nights earlier, shrapnel had hit the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie and the refectory. Surprisingly, none had damaged the jewel of Milan. For centuries the friars ate in front of the wall on which Leonardo had portrayed the twelve apostles and Jesus about to have their supper. When dawn broke, Father Acerbi saw that the explosion had interrupted that tradition, perhaps forever. Although the bomb spared Leonardo's masterpiece it was only temporary Without roof and without a wall, the delicate microclimate of the refectory was disrupted: the Last Supper was now exposed to the humid Milanese summer, which could have caused swelling in the wall and caused some fragments of the fresco to detach from the wall. Without a roof, a summer storm could have washed away the remains.

The bombed out church

Santa Maria delle Grazie 2023

Father Acerbi had already saved the friars of the monastery hiding them outside the complex of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Had they remained in the cellars under the church they would probably have died from the same bomb that d the cloister. Acerbi now tried to save the Cenacolo, he immediately warned the authorities of the damage to the refectory and left by car in search of help: He travelled about 600 kilometres in one day enlisting other Dominican friars who set to work in the rubble. Acerbi also managed to obtain waterproof sheets from engineers in Piacenza, with which he covered the Last Supper to protect it from summer storms. Acerbi and the others saved the Cenacolo, which reopened to the public in 1945.

The entrance to the miraculously surviving Cenacolo

183 Milanese were killed in the last attack. On the way back, Lancaster ( ED998) of 467 Squadron was shot down by a German night fighter , crashing near Chartres . Among those killed was Wing Commander Cosme Lockwood Gomm. An Anglo-Brazilian born in Curitiba and raised in Sao Paolo. The war was truly international . Lancaster ( ED498) of 207 Squadron was hit by flak and crashed at Beuzeval on the Normandy coast. Lancaster ( LM 337) of 49 Squadron was shot down and crashed at Cheronvilliers, near Rugles. Lancaster ( JA896) of 57 Squadron was nearly home safe, when it overshot the runway at Scampton killing the whole crew.

Aftermath

After the 16 August Bomber Command halted its attacks. The four August raids had caused over 1,000 dead and hit half of the buildings in the city, destroying or heavily damaging 15% of them and leaving over 250,000 people homeless. The work of 5,000 workers and 1,700 soldiers was needed to remove the ruins. Water, light and gas supply resumed within 48 hours, while public transport was nearly annihilated. It is difficult to put a precise number of the British and Commonwealth aircrew killed during the bombing of Milan . So ineffective were the Italian anti-aircraft defences that apparently less than twenty were shot down and killed in Italy. A much higher number were shot down by the German during the perilous flight through France and back or crashed through mechanical failures. It is possibly not more than a hundred in total . Even if they survived those isolated bombing raids on Italy, there is a strong chance that the same aircrew were killed on later raids into the Third Reich.

After the bombings , the Italian poet Salvadore Quasimodo, wrote the following poem entitled “Milano Agosto 1943”

“Invano cerchi tra la polvere,

povera mano, la città è morta.

È morta: s’è udito l’ultimo rombo

sul cuore del Naviglio. E l’usignolo

è caduto dall’antenna, alta sul convento,

dove cantava prima del tramonto.

Non scavate pozzi nei cortili:

i vivi non hanno più sete.

Non toccate i morti, così rossi, così gonfi:

lasciateli nella terra delle loro case:

la città è morta, è morta.”

Bomber Command Memorial London

Further reading

A short and interesting account of the bombing of Italy 1940-43