István Tóth-Potya - Forgotten Inter manager starts to get some recognition

While I was writing the shot blog about Gyula Feldmann, I recalled writing this one from a previous BlogSpot. Since the article on Gyula Feldmann makes a few references to István Tóth-Potya, it seemed fitting to bring them together in the same place. It is the original article slightly corrected. Since I originally wrote this there have been a couple of developments. Both the football club Ferencvárosi and the Hungarian Government neither whom were particularly well regarded (in the case of Ferencvárosi- more its fans than the club) have been commemorating István Tóth-Potya’s name.

In February 2021. István Tóth-Potya was added to the marble monument in the Raoul Wallenberg Holocaust Memorial Park in Budapest, the presence of his grandchildren

Yacov Hadas-Handelsmann, the Ambassador of Israel to Hungary stated that

“This man was a beacon in the darkest times humanity. He helped Jews knowing that he put his life at risk. “

Chief Rabbi Peter Kardos, recalled that the recognition was somewhat belated

“Fradi (Ferencvárosi) fans did not mention his name or what he did. They were afraid. During the 1950s communist regimes there was no place pr a man who was a Fradi player, who moreover saved Jews. “

As can be seen from the article below. Toth was active in the non-communist resistance to the Nazis and local Fascists, and so was subsequently airbrushed out of history, to preserve a fiction that only the Soviet army liberated Budapest. Hopefully, some of the other people mentioned below, will get similar recognition,

Events then moved on even further. Below, I mentioned that there seemed to be little public information on who Toth Potya had saved.

In July 2021, Ferencvárosi (FTC), filed papers with Yad Vashem Institute in Israel, requesting that Toth be recognised as one of the Righteous Among Nations. Up until 2020, of 27,712 awards made by Yad Vashem, 869 had been to Hungarians. The process of evaluation and the documentation remain confidential, and it could be a long process. There is quite a high bar to reach. The basic conditions for granting the title are:

- Active involvement of the rescuer in saving one or several Jews from the threat of death or deportation to death camps

- Risk to the rescuer’s life, liberty or position

- The initial motivation being the intention to help persecuted Jews: i.e. not for payment or any other reward such as religious conversion of the saved person, adoption of a child, etc.

- The existence of testimony of those who were helped or at least unequivocal documentation establishing the nature of the rescue and its circumstances.

In summary the case for István Tóth-Potya, is that he procured forged documents for Jewish -Hungarians to enable their escape and that he hid refugees in his house it specifically mentioned that he was responsible for saving Kalman Latabar, a comedian and actor and Hilda Gobbi, a famous theatre star. Possibly he also assisted in Gyula Feldman, but that is just my speculation. Ferencvárosi fans had developed a particularly unattractive reputation, which the club is apparently trying to clean up. The same could also be said of the current Hungarian Government. So, we can only hope that this is more than a PR exercise. Hopefully time will tell.

István Tóth-Potya. 1891-1945. Fiumei Road, Cemetery Budapest

Originally posted February 2019

A previous blog looked at the career of Hungarian Football Manager Arpad Weisz who was the youngest manager to ever win a scudetto In Italy with Inter in and who then went on to win two further scuddetti with Bologna. Weisz was expelled from Italy following the Racial Laws of 1938 and died in a Nazi Labour Camp in January 1944. Two lesser-known Hungarian managers, István Tóth-Potya and Géza Kértesz also worked In Italy in the same period. They too met a tragic fate at the end of the Second World War. Again, this was part of a longer piece, I thought I would publish it to mark the anniversary of their deaths on 6 February.

I started looking at István Tóth-Potya because he managed Inter, and my son and I were supporters. He seemed to be one of the many Hungarian managers passing through Italy at the time. Then I stumbled across a book in Italian, entitled “Due Eroi in Panchina”, (Two heroes on the bench) by Roberto Quartarone, which outlined the stories of Tóth-Potya and Kértesz. A remarkable story it is too, that these two Hungarian men should go from managing Italian football clubs to being shot at dawn in the courtyard of Budapest Castle, while Russian forces were literally less than a few kilometres away.

In November 2016, I happened to be in Budapest on business, I had a few hours spare and took a taxi out to the incredibly cold and bleak Fiumei Road, Cemetery. It is vast cemetery and thankfully, a very kind woman in the cemetery office helped me out. I wrote the names out for her, and she looked them up in the computer, she said “Ah, the footballers” and gave me very precise directions. I had the feeling that I may not have been the first to ask and that the route had been well travelled by many Italian football pilgrims before me. Probably inspired by Mr Quartarone’s book.

Géza Kértesz and István Tóth-Potya reunited in death

In reality, Tóth-Potya was not a hugely successful Inter manager, but the legacy of Kértesz is still remembered at many of the clubs he coached in Southern Italy at Salerno and Catanzaro and particularly in Catania. István Tóth-Potya started his playing career in the Budapest TC Youth Team in 1904. By 1906, he was playing for the newly formed Nemzeti SC from Terézváros in Budapest’s District IV, in central Pest. Nemzeti started in the Nemzeti Bajnokság 2 (The Hungarian Second Division or NB2) gaining promotion to NB1 in 1909. Tóth-Potya seems to have stayed there for six seasons before crossing down to join Ferencvárosi in 1912.

Ferencvárosi, is a southern suburb of Budapest, officially District IX, lying partly on the Danube and extending inland. By the end of the 19th Century, the district was heavily industrialized with five mills, slaughterhouses, and the Central Market Hall. The Ferencvárosi Sports Club was founded on 3 May 1899, and the football section on 3 December 1900.

At around the same time, the seventeen-year-old Géza Kértesz signed for Budapest TC. In the 1912-13 season, Tóth-Potya made 14 appearances in the championship scoring 13 times with Ferencvárosi finishing as Champions. In 1911, Blackburn Rovers and Oldham Athletic both toured Budapest and Vienna. On 25 May 1911, Oldham Athletic drew 2-2 with Ferenc and beat Magyar TK 1-2. March 1913, saw Oxford City playing Rapid Vienna, Budapest TC, Timisoara, Muegyetmi and Magyar TC. In 1913, Sunderland were back in Budapest, demolishing Ferencvárosi 0-9, Budapest Athletic 1-5 and less convincingly Magyar TK 2-3.

As well as the Hungarian League, Hungarian Clubs in the pre-war era also played in the Challenge Cup of Austria-Hungary. John Gramlick, who was one of the founders of the Vienna Cricket and Football Club in 1891, invented the competition. For the first seven seasons, sides from Vienna won the cup. After a three-year break, the Cup was held again the 1908 -09 season, when Ferencvárosi won 2-1 against Wiener Sport Club. On 29 May 1909 at the Millenaris Stadium in Budapest, Hungary played an international against England. It was Tóth-Potya’ s first game for the national side. England won 2-4. Among the scorers for England was Vivian Woodward who scored after 39 and 79 minutes.

Austria- Hungary was no backwater of the newly developing international football. Before the First World War, there was no shortage of foreign clubs touring Austria-Hungary. English Clubs made some suitably epic railway trips to take on Central European opponents once the domestic season had finished. The tours usually included a stop in Vienna to play one or two matches against Viennese clubs, and then they headed downriver to Budapest for another couple of fixtures, sometimes adding on trips to Prague or Munich. According to the Bradshaw’s Guide, the total journey from London to Budapest on the Ostend- Vienna Express was 1,686 miles and it would have taken 37 hours.

Somewhat later than Hungary, in 1910, the Italian national team played its first official game against France with a squad solely comprised of Italian citizens. The match took place at the Arena Civica di Milano. In front of the home-crowd, Italy got off to a good start and by half time were two goals up against the French, courtesy of goals from Lana and Fossati. After the break, the French fought back to 2-1, Lana scored again for Italy and then the French got another to make it 3-2. After that, the French team underwent a collapse, Rizzi and Debarnardi scored for Italy, and then Lana completed his tripletta with a spot-kick. The game finished 6-2 to the hosts.

Then, the Italians set-off for an away game against the Hungarian national side. Setting off from Milan’s old Central Station in the Piazza Fiume[1]. The train journey into Central Europe would have involved the route, Milan to Verona, Verona up through the Brenner Pass and most probably via Vienna to Budapest, arriving at the imposing Eastern Station. This was actually a Velodrome, with the centre space used for football, in the eastern part of Budapest not far from the station. It turned out that the result against France was something of a false start, the Italians were down by one goal at 28 minutes and then conceded another five until the 88th minute Rizzi managed a consolation goal, for the match to finish 6-1 to the Hungarians. 0n 6th January 1911, it was the turn of Milan to welcome the Hungarians to the Arena Civica, where the only goal of the match by Imre Schlosser on the 22nd minute, settled the match in favour of Hungary.

In the summer of 1912, both the Italian and Hungarian national sides made the long trip to Stockholm for the summer games of the Fourth Olympiad. István Tóth–Potya went with the Hungarian squad. In a pre-Olympic friendly match in Oslo on 23 June, Tóth- Potya scored his first goal for the Hungarian national side in a 0-6 thrashing of Norway. Neither Hungary nor Italy did well in the tournament proper. On 30 June in Solna, Hungary lost 7-0 to an England side captained by Vivien Woodward. Harold Walden of Bradford City scored six and Woodward the remaining goal.

Harold Walden of Bradford City- scored six against Hungary

On 29 June, Italy fared little better losing to Finland 2-3 after extra-time. England subsequently, took the Gold Medal having beaten Finland 4-.0 in the semi-finals and Denmark 4-2 in the final. The Olympic Competition including a Consolation Tournament for the seven losing teams from the first two rounds. Italy beat Sweden 1-0 to progress and lost 5-1 to Austria in the semi-finals. Meanwhile, Hungary beat Germany 3-1 with a hat trick by Schlosser and went on to beat Austria 3-0 in the Consolation Final. Officially, the Hungarians finished fifth in the football competition.

Hungary continued their summer 1912 tour with a trip to Moscow for two games against Russia. On 9 July 1912, the Hungarians won 0-9 at the SKS Stadium in Moscow. After, accompanying the team as an unused substitute, Tóth-Potya finally got to play against Russia in the second game on 14th July, The Hungarians won by an even greater margin of 0-12, with Tóth-Potya scoring in the 79th minute. In the days before air travel, the Hungarians had made a truly epic tour of the European Railway system. The train trip from Christiana across Norway and onto Stockholm was around 13 hours. The evening sleeping car train from Christiana left at 6.05pm and arrived at 7.08 the following morning. To get from Stockholm to Moscow, was an even more marathon endeavour. The first leg involved taking the 7.30pm steamer from Stockholm arriving at Abo in Finland at 9.30 am, before joining the Russian Railways for the journey from Abo to St Petersburg- a total journey time of around 25 hours. After a brief stay in St Petersburg, a further night train from St Petersburg at 9.30pm would have seen the team arriving in Moscow at 8.15 in the morning. It is truly amazing that the Hungarians were in any shape to play, let alone so comprehensively beat the Russians at home. A minimum journey time of 36 hours, but most probably in the region of a full two to three days, depending on how well the connections went. Moscow back to Budapest, via Warsaw and Vienna would have taken another 45 hours more or less, with everything going well. After such a trip, the exhausted players must have been infinitely relieved as their Hungarian Railways train pulled into Budapest’s West Station.

In the 1913-14, season Tóth-Potya turned out for Ferencvárosi, 17 times in the NB1 and scored 14 times. That season, they finished runners up to MTK. In the winter break, they toured France and Spain, going from Paris to San Sebastian and Bilbao before returning to Budapest. Following the end of the Hungarian Season, Ferencvárosi hosted Celtic FC and Burnley FC in Budapest. They would be the last British Clubs to play in Hungary for many years. The last club game of that season was a 1-2 victory over Rapid Wien in Vienna on 7 June. Imre Schlosser scored the first, Tóth-Potya the second. In June 1914, Tóth-Potya had made the long journey back to Sweden for another tour with the Hungarian National Team. At the Rasunda IP in Solna, on the 19 June, Hungary won 1-5 with goals from Payer, Tóth-Potya, Basz, Racz and Schlosser. The return match on 21 June, it was a 1-1 draw with the inevitable Schlosser scoring for Hungary. Seven days later, events far to the south of Stockholm were to have a far-reaching effect on the young Hungarians’ football careers and lives in general.

On 28 June, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Hapsburg throne – future Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary made a somewhat ill -advised state visit to Sarajevo. In the morning, a bomb was thrown at the archducal car. It bounced off and exploded against the next car injuring two of the Archduke’s staff officers. The Archduke made a bad situation worse by deciding to carry on with his official tour of Sarajevo and going to the hospital treating the injured officers. On the way, his car took a wrong turn and the driver slowed down to reverse, almost directly in front of Gavrilo Princip an accomplice of the morning’s perpetrators. Princip took his chance and fired two shots fatally wounding the Archduke and his wife. As events spiralled rapidly out of control, ultimatums followed and mobilizations. On 28 July, Austria- Hungary declared war on Serbia and on 30 July, the Russians mobilized. On 4 August, German troops crossed into Belgium in defiance of a British ultimatum and at 11pm on 4 August 1914, the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. By the next day, the nations that competed in the 1912 Olympic Football and whose domestic clubs played each other in summer tours were all at war with each other, with Germany and Austria-Hungary ranged against the United Kingdom, France and Russia. For the time being Italy, although nominally allied to the Central Powers managed to remain neutral. Men, who had cheerfully been kicking footballs at each other, now volunteered, or conscripted for a far more deadly game. The railway networks, which they had used to crisscross the continent on football tours, were used to transport newly mobilized armies and war matériel from one front to another.

Tóth- Potya continued to play football, even after Italy had entered the war on the allied side and Russian offensives started to turn on Austria- Hungary. On 4 June, the Brusilov offensive began with a 1,938-gun barrage on a 250 km front running from the Pripet Marches to Bukovina. Several hours of artillery breached the Austro- Hungarian barbed wire defences in at least 50 places and the Russians swept forward capturing around 26,000 Austro-Hungarian troops in one day. On 9 June, the Austro-Hungarian commander, General Pflanzer- Baltin announced a general retreat. The Russians continued to advance through abandoned Austro- Hungarian positions and on 15 June, Brusilov announced that the Russians had thus far captured 2,992 Austro-Hungarian officers and 190,000 men, in addition to 216 heavy guns, 645 machine guns and 196 howitzers. That worked out at roughly one third of all the Austro- Hungarian forces deployed on the front. On 20 June, the Russians entered Czernowitz the most easterly Austro- Hungarian city. In the end, the Germans took over command and steadied the Eastern Front. The Russian offensive drew to a halt in October 1916.

On 1 October 1916, Austria and Hungary played at the Ulloi-ut with the Austrians winning 2-3. On 8 November, the Hungarians travelled to Vienna where the two countries played a 3-3 draw. That turned out to be the last international under the Dual Monarchy and the last of the war years. The situation in Hungary started to deteriorate rapidly.

On 25 November 1917, some 100,000 Hungarian workers demonstrated in Budapest calling for immediate peace and a Bolshevik Revolution. The Hungarian government terminated its union with Austria on 31 October 1918, officially dissolving the Austro-Hungarian state and proclaiming a Republic. On 13 November 1918 in Belgrade Hungarian Prime Minister, Károlyi signed an armistice with the Entente. Hungary effectively lost Transylvania south of the Mureş river and east of the Someş river, to Romania; and Slovakia, which became part of Czechoslovakia. Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Hungarians now found themselves stranded in Romania and Czechoslovakia. There followed, a brief Workers’ Soviet in Budapest , a White Terror, invasion by the Romanians and the confirmation of the less of territory at the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. It seems truly surprising in all the chaos that the Hungarians continued to play football.

In the 1918-19 season, a full season of Nemzeti Bajnokság I was played. Tóth-Potya made 20 appearances for Ferencvárosi in that season, scoring eight times. The 1920-21 Season of the Nemzeti Bajnokság I, seems to be the last time that Kértesz and Tóth-Potya played in the same Ferencvárosi side. Although, Kértesz was still on Ferencvárosi’ s books for the 1922-23 season he does not seem to have started any games. Tóth-Potya played in 21 games. Gradually Hungarian football started to become outward looking again. In 1922, Italy was the first of Hungary’s former enemies to welcome back a football team. On New Year’s Day 1922, Ferencvárosi beat Spezia Calcio 1906 in La Spezia, they played again the next day beating them again. They went on a tour of Italy, taking in Livorno, Pro-Vercelli, Firenze and Venezia.

In March 1923, Ferencvárosi toured Spain again playing Barcelona, Madrid, Racing Santander and Real Sociedad. At Christmas 1924, Ferencvárosi made a second tour of Italy passing through Florence, Modena, Cremona, Livorno, Rome and Vercelli A year or so later, Géza Kértesz found work as a player/manager in the Second Division side Spezia in the Northwest of Italy. La Spezia, in the 1920s a city of approximately 60,000 was one of Italy’s chief naval ports with its 2,200-acre Naval Arsenal. The main street the Corso Cavour led down to the Public Gardens and the sea- front with a spectacular view down the Golfo della Spezia with the Apuan Alps running behind. Although he was now 31, in the 1925/26 season Géza Kértesz played in 13 games and scored a goal against Savona.

Tóth-Potya remained with Ferencvárosi in Hungary, where in the 1925/26 season; he combined the role of player manager. That season he finally managed to overcome the dominance of MTK Budapest interrupting their 10-year winning streak and claiming a 9th title for Ferencvárosi. On 2 May 1926, Tóth-Potya turned out for the last time for the Hungarian national side, in the traditional derby game against Austria at the MTK Stadium in Budapest; the Hungarians lost 0-3. While Kértesz was building his career in Italy, Tóth-Potya continued to strengthen Ferencvárosi taking them to another two Hungarian championships followed by two second-place finishes.

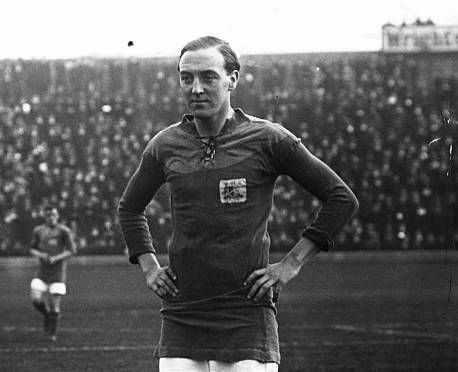

István Tóth-Potya

Géza Kértesz

In 1928, a wider stage opened for Tóth-Potya with Ferencvárosi qualifying as Hungarian champions for the Mitropa cup. Introduced, in 1927, the Mitropa Cup was a predecessor of the Champions League, played between the champions of Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. In the first round, Ferencvárosi annihilated BSK Beograd, 13-1 on aggregate. In the semifinals, they beat Admira Wien 3-1. In the first leg of the final at the Ulloi uti in Budapest on 28 October 1928, Ferencvárosi administered a 7-1 thumping to Rapid Wien. In the return leg on 11 November at the Hohe Warte in Vienna, they lost 5-3- but still won the cup on aggregate.

Meanwhile, Kértesz was beginning a journey which was to lead down the length of Italian Peninsula, After Spezia he moved to Carrara Calcio, in the then thriving Ligurian town renowned throughout the world for its white marble. His stay in Carrara was brief. Sometime in 1927, he arrived at Sporting Club Viareggio in the popular seaside resort on the Tuscan coast. At the end of the 1927-28 season SC Viareggio topped Girone C of the Italian Second Division (North) and were promoted to Girone A of the First Division (North). They finished the 1928-29 term in eighth position. So far, Kértesz’s Italian odyssey had taken him the relatively short trip from Spezia to Carrara to Viareggio, not more than 100km in total. At the time, Southern Italian football was starting to get more ambitious and in summer 1929, Kértesz received an offer from Salernitana way down south in Campania.

Meanwhile, Tóth- Potya’s horizons were also expanding. Having toured extensively in Europe as well as to Egypt, it was little surprise that Ferencvárosi’s next tour was to South America. European clubs had been touring South America on a regular basis since the early years of the century, especially Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil. The honour of the first official tour seems to belong to the English club, Southampton who in 1904 played a series of matches in Buenos Aires and Montevideo. The first tour by a club from mainland Europe was by Torino in 1914, which proved to have a seminal effect on football in Brazil at least. After a pause for the war, clubs from England, Italy and Spain resumed tours to Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay- they included Chelsea, Genoa, Deportivo Español, Real Madrid, Celta Vigo and Barcelona.

Ferencvárosi, were therefore following a well-trodden path when, at the end of the 1928-29 season, they set off from Europe for their South American Tour. The long journey involved the train down from Hungary to the Italian Port of Genoa where they embarked the transatlantic liner Giulio Cesare of the shipping line Navigazione Generali Italiana for the 11-day voyage to Santos, the Brazilian port of entry for São Paulo. They played their first match in on 30 June against a São Paulo select side winning 1-2. They then made the journey from São Paulo to Rio de Janeiro. Then it was back to Sao Paolo for a fixture with Palestra Italia, before touring Uruguay and Argentina. The final match was played in Sao Paolo on 17 August, after which it was back to Santos for the voyage back to Europe and preparation for the 1929-30 season.

While, he was at Salernitana , Kértesz was poached by Catanzaro in Calabria in mid-season. Due to the irregularity of his position, he was forced to go back to Salernitana to see out the season but whatever his thoughts about that, he still got them promoted at the season’s end. At the start of the 1931-32 season, Kértesz was finally able to move to Catanzaro. At the end of the 1932-33 season, Kértesz had overseen Catanzaro’s promotion to Serie B. In May 1930, Italy had reached the finals of the 1927-30 Coppa Internazionale series. On 11 May they met Hungary at the Ulloi Uti stadium in Budapest. The wounds of the First World War, when Italians and Hungarians had battled over the plateau of the Karst were still fresh in the mind. On the way to Hungary, the manager took the Italian national team on a pilgrimage to the battlefields of the North-East. The manager, Vittorio Pozzo, asked the squad whether they wanted the “infamy of a new Caporetto or the glory of Vittorio Veneto”. In front of an incredulous Hungarian crowd, the fired-up Azzurri won the game 5-0. Unfortunately, the Bohemian Crystal trophy was smashed to smithereens when the train bringing the triumphant team back to Italy, stopped abruptly outside Monfalcone. Thereafter, apparently Vittorio Pozzo always carried a fragment of the crystal as a keepsake.

Meazza, inspired not only the national side but also Ambrosiana. On the third to last game of the season, Ambrosiana faced Genoa at the Arena Civica. Anticipation was high, the Nerazzurri had previously won championships in 1910 and 1920, would 1930 be another lucky year. Arpad Weisz became the first foreigner and the youngest manager ever to win the Italian Championships at the grand-old age of 34. In 1931, Ambrosiana- Inter ( as they were called at the time ) thought that they could try and repeat Weisz’s magic, with another Hungarian manager and called on Tóth-Potya . The season did not go so well and Ambrosiana- Inter finished in sixth place. Tóth-Potya was fired, and Arpad Weisz returned.

After the disappointing 1931-32 at Inter, Tóth –Potya returned to Budapest to take charge of Ujpest for the 1932-33 season. In his first year, he took the team to the top of the Hungarian League. This was to be his fourth Hungarian championship Kértesz went even further south. In the 1933-34 season he took over as manager of Società Sportiva Catania, Kértesz was hired by il Duca Vespasiano Triogona di Mister Bianco, an ambitious man with a huge fortune based on his extensive estates in Eastern Sicily who has prepared to make the investment in players and coaching staff to take Catania forward. However, Tóth-Potya was not quite finished with Italy and for the 1934-35 season he returned to manage Unione Sportiva Triestina Calcio 1918, in Trieste. He managed Trieste for two whole seasons finishing 11th and then 6th in Serie A.

In the 1935-36 season, Weisz, Kértesz and Tóth-Potya were all managing clubs in Italy. Weisz was at Bologna, Kértesz was still at Catania and Tóth-Potya at Trieste. They were among many Hungarian managers that season, Karl Csapkay at Palermo, Ferenc Hirzer at Salernitana, Josef Viola by now at SS Lazio, Arpad Hajos at Modena, Gyula Feldmann at AS Torino, Ernest Erbstein at AS Lucchese. Of his Hungarian contemporaries, Weisz had undoubtedly the best track record in Italian Club management at that time.

At the end of 1936, the il Duca having blown a substantial fortune on his beloved SS Catania, so much so that he had to sell some of the family estates decided to call it a day and retired to look after his agricultural interests. . The club was renamed Associazione Fascista Calcio Catania. Kertesz left at the end of the 1936-37 season and found employment in the city of Taranto, At the northern extremity of the Gulf of Taranto, Taranto was a lively and important city of around 88,000 inhabitants and the second naval dockyard in Italy after La Spezia.

Meanwhile, not long into the 1936-37 season, Tóth-Potya abruptly left Triestina. Officially, this was for health reasons, although his departure was rumoured to relate to his opposition to the Italian invasion of Abyssinia. Weisz was dismissed from Bologna and subsequently expelled from Italy following the Racial Laws of 1938. With Tóth-Potya already back in Hungary, only Kértesz remained involved in Italian football and in June 1939, he was appointed manager of SS Lazio in Rome. His first task was to accompany SS Lazio on a football tour into the dark heart of Nazi Germany. Owing to some difficulties in the travel arrangements, Kértesz’s Lazio side only arrived in Karlsruhe for their first match on Saturday 17 June, a few hours before the kick-off time following an overnight train journey from Rome. Despite the travel difficulties and the absence of some of their leading players, they went on to beat the home team 0-2. The next stop was Ludwigshafen where with a breath-taking display of attacking football, they won 0-5. The following Saturday, they had a slightly tougher time in Wiesbaden. A torrential downpour in the morning had reduced the pitch to a swamp, according to the Italian press – the ball was not in accordance with regulations and four members of the German national side playing under assumed names had mysteriously reinforced the local team. Nevertheless, Lazio still managed to win 1-2. The following day, they did it again winning at Kaiserslautern 1-4. All in all not a bad start for Kértesz’ s first outing with the team. Four out of four victories, 13 goals scored and only two against. After the summer break, Kértesz gathered his squad together for a training session at the stadium on 21 August, putting them through some intense athletic training before they even touched the ball. On 27 August, the Lazio A Team beat the B Team 5-0 and Kértesz looked forward to a pre-season friendly with Napoli in the following week.

On the night of 31 August, the Germans faked an attack on a radio transmitter in the town of Gleiwitz on the Polish – German frontier and the following day using this as one of their many excuses launched the Blitzkrieg invasion of Poland. On the morning of 3 September, as Kértesz and his Lazio team prepared for their match, Sir Neville Henderson, the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the Germans an ultimatum that unless they undertook to withdraw from Poland by 11am a state of war would exist between the countries. Although a crowd of 6000 turned up to see the friendly match in Naples, by the 3.30 pm kick –off time, most of Europe was at war again and the final score of 1-2 to Lazio must have seemed irrelevant. As the afternoon progressed, hundreds of miles to the North German bombers flattened the undefended town of Sulejow in Poland and as thousands of the civilian population fled into the woods other German planes machine-gunned them from the air. For Kértesz it was only a matter of time before his homeland of Hungary and his adopted homeland of Italy were drawn into the conflict.

Kértesz, started the 1940-41 season as manager of Lazio, but was dismissed after six games and replaced by fellow Hungarian Ferenc Molnar. While in Rome, Kértesz became acquainted with Pál Kovacs, an exiled fellow Hungarian. It was the start of a friendship, which would ultimately end badly for both. On 3 September 1943, the Western Allies launched Operation Baytown, the invasion of mainland Italy. At 4.30 am, British and Canadian troops commanded by General Montgomery crossed the Straits of Messina from Sicily and landed near Reggio Calabria. The same afternoon, the Italian Government signed an Armistice with the Allies. On 9 September, the Allies liberated two Italian cities where Kértesz had followed his career, Allied troops landed near Salerno while British Airborne troops seized Taranto. Meanwhile, on 10 September 1943, the Germans occupied Rome. With most Italian football now suspended; it was definitely time for Kértesz to go back to Hungary. On 13 October, while allied forces moved north towards Rome, the new Italian Government which had fled from Rome to Brindisi, declared war on Germany. For most of the winter of 1943-44, the Allies were held up at Monte Cassino until on 22 January an ambitious naval landing at Anzio started to put more than 36,000 men ashore north of the German defence line. Finally, on the 4 June 1944, American units reached the centre of Rome and the next day they triumphantly entered the Italian capital in force. Accompanying the Allied Armies up the Italian Peninsula were the men of the United States Office of Strategic Services (OSS). They were particularly interested in talking to some Hungarian émigres in Rome, the “Free Hungarian Association.” Four members of this group would go on to play prominent roles within the OSS: Aradi, Gyula Magyary, a priest, László Kiss, a film director and Pál Kovacs, a labourer.

In the disorganization, which followed the liberation of Rome, the Allied intelligence players rushed to secure sources, agents, and information. This saw not only X-2 and SI competing in the city, but also the Americans and the British. Initially the Americans had a number of concerns regarding the use of the Hungarian exiles, particularly regarding their security, their relations with the Horthy regime and their past connections with the British. However, in the end the OSS were won over and started planning to use some of the individuals for missions in German occupied Hungary.

In Hungary, the political situation continued to deteriorate throughout 1944. The Hungarian Prime Minister, Miklos Kallay with the approval of Admiral Horthy was discussing Armistice Terms with the Allies, Hitler invited Horthy to a meeting at the Palace of Klessheim, near Salzburg on 15 March. While he was out of the country, German troops quietly began the occupation of the country. On 19 March, Edmund Vessenmeyer was appointed Reich Plenipotentiary in Hungary. The evening of 19 March 1944, Kértesz was occupied with an Ujpest away game against Nagyvarad, a Romanian side playing in the Nemtzi Bajnaksag. Ujpest finished that season in fifth place. It was to be Kértesz’s last full football season. Not surprisingly, the official 1944-1945 Hungarian Football season was abandoned after four match days in September 1944.

In October 1944, Kertesz’s old associate, Pal Kovacs together with Magyary arrived in Slovakia as part of the American OSS Mission, named Bowery/Dallam. On the 7 October the mission Bowery/Dallam left Bari, landing at Tri Duby in Slovakia. They crossed into Hungary on the night of 11 October. Magyary proceeded to Esztergom intending to meet with his close-friend the Prince-Primate. The Prince-Primate, upon meeting Magyary, immediately hid him while Magyary explained his mission. Serédi acknowledged Magyary’s undertaking and provided him with the means to get to Budapest (again by train) where Magyary contacted a friend who was professor of law at the University of Budapest and told him to alert Horthy to his arrival. At 9 am on the 14 of October, General Pál Pongracz, a member of the Regent’s military cabinet retrieved Magyary and brought him to the Royal Palace, where he met with various officers of the Regent’s military cabinet discussing with them his mission. Nearly 12 hours later, Magyary had his audience with Horthy, telling him “I am of the Apor group. I come from the Allies, we outside the country see that the war is already lost for Hungary, it is high time that we made ourselves active as such, Hungary should surrender unconditionally to the United States, Great Britain and USSR.” Horthy concurred stating “The interests of Hungary are more important than my personal safety, I would be willing to put my head under the guillotine if it would save Hungary.” All told, Magyary and Horthy spoke for an hour and a half. Subsequently, Magyary contended that he had provided Horthy with the stimulus to make the announcement on the 15th citing that he “recognized words and phrases from their conversation. At 2pm on 15 October 1944, Horthy announced on national radio that the government had reached armistice terms with the Soviet Union. The Germans had been aware of Horthy’s discussions with the Soviets and had already set in motion plans to replace his government with forces loyal to them. With Nazi help, the Arrow Cross Party seized control of the radio station and later in the afternoon, issued a proclamation in the name the Chief of the General Staff, General Vörös to troops explaining that the Regent’s earlier proclamation concerned only negotiations for an armistice and not an order for the cessation of hostilities. The proclamation instructed the troops to continue fighting. Meanwhile a German convoy including four Tiger II tanks led by Otto Skorzeney arrived at the Vienna Gates on Castle Hill. Horthy recognized he had no means to fight the Germans and ordered his troops not to resist. He was taken into German custody and forced to sign a document abdicating the Regency in favour of the Arrow Cross Leader Ferenc Szálasi. All afternoon and evening Tóth and Géza Kértesz in common with the other residents of Budapest kept vigil by the radio for updates on the ever-changing situation. Martial music filled the time between increasingly confusing proclamations. At 9,20 in the evening Ferenc Szálasi came on air and read out his first “Order of the Day.” A few minutes later followed a proclamation of the Arrow Cross Party calling for the arrest and execution of the Jewish stooge and traitor, the ex-Regent, Nicholas Horthy. Szálasi’s proclamation, addressed to the officers and troops of the Hungarian army, assured them that since Horthy had broken his oath of office by seeking an alliance with the Bolsheviks, they were no longer bound by their oath to the Regent. Starting today their new commander was Ferenc Szálasi., the saviour of the country, who would fight with them to the last drop of his blood to save Hungary from the indignity of a new Trianon Treaty. “Death to the former Regent and his accomplices! Long live our country! Long live Szálasi! “

Pál Kovács had split up from Magyary and upon nearing, the Hungarian frontier made his own way to Budapest. While Magyary’s mission was to liaise with the Hungarian Government, Kovács’ assignment had been to organize resistance, specifically among Hungarian factory workers. Kovács and Magyary met one last time in Budapest, at a time most likely shortly before or after the German coup. In Budapest Kovács sought out Géza Kértesz whom he had met in Rome some years previously. Kovács purportedly informed Kértesz that he was a member of the US Army and had parachuted into Slovakia with an American lieutenant, Tibor Keszthelyi. Kovács claimed to be chief organizer of the “OSS Totis-Dallam group” and asked for Kértesz’s assistance in creating a resistance group. Kértesz agreed and contacted his friends, organizing a network around their apartment at the Grof Zichy Jenő Utca 40. The Dallam group met there nearly every night, excepting those when Kovács was hiding in Rákospálota, a suburban district of Budapest. The Dallam group “observed German troop movements, air force concentrations, prepared cryptograph messages in the shop of Gyula Toghia and forwarded the messages by courier to Leva in Slovakia, where an OSS short wave radio was located. They also purchased German uniforms and small arms.”

After Szálasi came to power, normal life in Hungary was disrupted. Shops and factories closed; rumours about rapid Russian advances were confirmed by people who fled to the capital from towns south and east of Budapest. Szálasi refused to face reality ordering shops and factories to be opened and civil servants to report to their jobs. He ordered a curfew after dark and a ban on assemblies of more than three persons. General security was tightened; martial law was extended to many offences including “race pollution,” bribery and profiteering; the spreading of defeatist rumours was made punishable by death. In a desperately foolish effort to achieve victory, Szálasi ordered general mobilization: every able bodied man between 12 and 60 was ordered to report for military service or other defence work. As conditions deteriorated, even health exemptions were revoked. Szálasi published a decree declaring that all Jewish property belonged to the state. He did not recognize the validity of safe conduct or foreign passes issued to Hungarian Jews. Budapest’s Jewish population was now rounded up in great numbers and taken to ghetto houses. The Germans needed Jewish labour to build fortifications against the advancing Russian army, and Eichmann asked for 50,000 Jews. Szálasi sent 25,000 on condition that they remained under Hungarian supervision. They were supposed to be sent by rail, but when transportation was not available, the Jews were compelled to make the journey on foot in threadbare clothes, in the freezing cold. Many thousands died in these death marches. Vessenmeyer wanted the Jews out of Hungary because he was afraid of their resistance as the Russian army surrounded the German Garrison. Many more would have died in Hungary, but for the selfless band of honourable consuls from the neutral powers who signed visas, provided documents and diplomatic protection- they included Raoul Wallenburg of Sweden, Alberto Carlos de Liz-Texeira Branquinho of Portugal, Frederic Born of the Red Cross, Carl Lutz of Switzerland and the Italian Giorgio Pelasca. On 29th October, the Soviet Red Army in conjunction with Romanian allies, started its offensive against Budapest and by 7th November, Soviet and Romanian Units were entering the Eastern Suburbs of the City. The Dallam Group was one of many resistance groups to form in Budapest following the Arrow Cross take-over. The fact that so many were betrayed and shut down with their members being killed by the Arrow Cross secret shows the moral courage that Tóth-Potya and Kértesz exhibited by taking the path of resistance. The Liberation Committee for the Hungarian National Uprising (MNFFB) was founded on 9th November and its military arm on 11th November with General Janos Kiss as its Chief of Staff . The MNFFB hoped to prevent the siege and destruction of Budapest by opening the front-line to the Soviets and triggering a simultaneous uprising. On 22nd November the military staff of the MNFFB were betrayed and caught up in a violent shoot-out with the gendarmerie and Arrow Cross militiamen. Subsequently, the majority of the organization numbering several hundred, were rounded up. General Kiss and his deputies were sentenced to death by a special court of the Hungarian Army and executed in the military prison on Margit Boulevard on 8th December.

On 6 December, before the Dallam Group could take any effective action, the Arrow Cross and Germans rounded up most of the members. The reasons for this are reported as relating to Kovács’ indiscretion in a bordello he frequented, however, this is only partially true. According to the postwar investigation of the operation, Kovács had attracted the attention of a prostitute at a bordello, Mária Benyi and became a regular client, visiting her at her apartment. Kovács informed her of his role within the American secret service. This, Benyi relayed to her pimp, Gábor Dosa, an Arrow-Cross Party member. Dosa disliked the amount of attention Benyi paid to Kovács and so, on the 6 December 1944, in in the late afternoon when Kovács visited Benyi and she asked Dosa to leave, he walked to the Headquarters of Hungarian Counterintelligence and within half an hour returned with several detectives who arrested Kovács. Kovács had a notebook on his person with the names of the members of his network as well as their addresses; his network was finished within a matter of hours. The secret police arrested most of the group members at their homes.

It is not really clear, how deeply Tóth and Géza Kértesz were involved in the Dallam network. Their names were on the list and that was enough for the Arrow Cross. At the time they raided his house, Kertesz was out. The secret police arrested his wife Rosa. Nino Kertesz went looking for his father finding him in a local bar. In order to try and spare his family from further harm, Kertesz gave himself up to the authorities. The Soviets continued to encircle Budapest. By 27 December 1944, they had taken Ferenginey Airport, some 20 km from the centre. Meanwhile, in the west of Pest the was similar heavy fighting around the Western Railway station less than a 2km from the Hungarian Parliament and the Danube. The Germans decided to abandon Pest and cross the river to make their last stand in Buda. On 18 January 1945, despite the protests of their Hungarian Allies, German sappers blew up sections of the historic Chain Bridge and Elizabeth Bridge to cover their retreat into Buda, leaving the Soviets and Romanians in possession of Pest. As they withdrew from the ruins of Pest, the Germans took their prisoners with them, installing them in the old prison of Fo Utca on the other side of the Danube.

For Tóth and Kertesz , imprisoned and besieged in Buda and totally at the mercy of their German and Arrow Cross persecutors, life must have become a living hell. It was not just the Soviet artillery, that relentless pounded Buda. In early January, the prison on the Fo Utca received a direct hit from American bombers. Flying Fortresses flying from American bases in the south of Italy, where Kertesz had made his career in the lower leagues. As Fo Utca became less secure and the defensive perimeter in Buda continued to shorten, the prisoners were transferred up the hill to the dungeons of the Interior Ministry, which had by now moved to the Buda Castle.

Buda Castle, where hours before the Soviet Army arrived, István Tóth-Potya and Géza Kértesz were executed. Who in the struggle against Nazism and for their country sacrificed their lives for the freedom of people.”

For, the Germans and their remaining Hungarian Fascist allies, it must have been clear that the game was very nearly over, In scenes repeated all over Europe, the SS began to take its final revenge on those who had opposed them. On the 6 February 1945, István Tóth-Potya and Géza Kértesz were executed in the courtyard of the Interior Ministry at Budapest Castle. They both died together at dawn, men who despite their travels and their internationalist outlook, were both patriots who had returned to their country and its hour of greatest need. Honourable men motivated by decency and a desire to try and save both their fellow men and their native land. Later that day, the Red Army captured the strategic Eagle Hill in Buda, which finally allowed them to direct fire on the German positions below. On 14th February the remaining defenders of Budapest surrendered unconditionally. Too late for Tóth-Potya and Kertesz. The Arrow Cross and Nazis disposed of their victims in unmarked graves.

After the war, the graves were slowly uncovered, and the bodies exhumed for identification. It took nearly a year to identify both István Tóth- Potya and Géza Kértesz . On 3 April 1946, the two friends were given a proper burial in the Kerepesi Cemetery in Budapest, as well as hundreds of ordinary mourners there were leading representatives from the Ministry of Culture and Sport, from the MLSZ, Ferencvárosi and Budapest TC. There were also representatives of the Italian Community in Budapest. The graves are still there today in a quiet almost abandoned corner of the cemetery not far from the Kossuth Memorial and from the well-tended graves of the victims of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising. They have not been forgotten though; there were fresh flowers on both graves when I visited the cemetery in November 2016.

Kértesz and Tóth- Potya are further commemorated by a plaque on the outside of Budapest Castle, which reads:

“At the beginning of 1945 in this building (the ex- Ministry of the Interior) resisters of various nationalities were incarcerated by the Gestapo. There were 350- for the most part soldiers, students and Hungarian forced labourers – but also Americans, Bulgarians, French, Polish, Germans, Italians and Russians- around a quarter of those detained were executed. These are the heroes, Lajos Kudar (colonel of the Gendarmerie), Elfrida Bakalas( Poland) , Lujza Brem, Genevieve Britsche ( France) , Andre Derret (France), Von Homburg (First Lieutenant- Germany), Erno Janosi, Miklos Janosi, Geza Kértesz, Pal Kovacs (First Lieutenant- United States) , Pierre Paulin( France), Istvan Toth-Potya (First Lieutenant) . Who in the struggle against Nazism and for their country sacrificed their lives for the freedom of people.”

While Tóth-Potya was not so well known in the English-speaking world, he was clearly not forgotten in Hungary, you only have to search the name on the internet to uncover tens of discussion boards and tributes from Ferencvárosi fans unfortunately mostly in Hungarian, a particularly difficult language to translate. It is fair to say he is remembered as a club legend at Ferencvárosi, and his memory remains deeply respected. Géza Kértesz seems lesser known in Hungary but that is also understandable since he spent his finest days in Italy. But slowly the Italians began to wake up to his memory. In 2015, after a long campaign, the City of Catania named a road after Géza Kértesz , in the northern part of the city not far from the football fields of the University of Catania. He is also well remembered in Bergamo with a sports complex named after him.

In July 2018, Ferencvárosi paid tribute to Tóth-Potya. Ferencvárosi officials, leaders of Hungary’s Jewish community, and representatives of the World Jewish Congress took part in commemoration of Tóth ahead of the team’s Europa League qualifying match against Maccabi Tel Aviv “I hope he can serve as an example for people who want to create similar paths in their own fields,” said his grandson, also called Istvan Tóth. Ferencvárosi, which had faced fines and other disciplinary measures for its fans’ racist chants or behaviour, dedicated the match to Tóth’s memory, and children escorting players to the football pitch wore T-shirts with his likeness. Tóth helped “several hundred Jews escape Nazi custody and death,” said Igor Ujhazi, representing the WJC.

“His heroic deeds teach us that sportsmanship can be seen as an enduring personal characteristic, conceptualized in virtues such as fairness, justice, courage and persistence.”

On 12 July 2018, the World Jewish Congress published a short video commemorating Tóth- Potya and Kértesz on social media.

Maybe, some of the Italian Press articles have got a little carried away in referring to Kértesz as a Hungarian Oskar Schindler, the exact number of Jews saved the Dallam network saved is unknown, although as noted above the WJC recognize hundreds. After the war, the Soviets wrote the history and with their communist allies, tended to stress the role of the communist resistance in Hungary and downplay the role of liberal or conservative groups, such as Dallam. Italian articles also refer to both players as being recognized as being among the “Righteous among the Nations”. A check on the database of Yad Vashem , does not include them as officially recognized among the more than 26,000 officially recognized Righteous, including 844 Hungarians. That is in no way to belittle their achievements or the sacrifice; the Italian Press can just be a little florid at times. Anyway, the Monument at Yad Vashem carries the inscription in Hebrew “whoever saves one life, it is as if he saved an entire universe”, so clearly in anybody’s book both Tóth and Kértesz earned the right to be called Righteous.

Ferencváros South American Tour 1929 Jun 30 São Paulo Select 1-2 Ferencváros: Jul 4 América (Rio de Janeiro) 1-1 Ferencváros; Jul 7 Rio de Janeiro Select 3-3 Ferencváros; Jul 11 Brazil 2-0 Ferencváros Jul 14 Palestra Italia (São Paulo) 5-2 Ferencváros Jul 21 Uruguay 2-3 Ferencváros Jul 25 Montevideo Select 1-4 Ferencváros Jul 28; Uruguay 4-0 Ferencváros ; Aug 1 River Plate 3-4 Ferencváros , Aug 3 Peñarol 2-0 Ferencváros ; Aug5 Racing Club 1-2 Ferencváros Aug10 Argentina 2-0 Ferencváros

[1] The old Central Station was located in the current Piazza de Reppublica – about 1 Km south of the current Central Station.