Canadians in Buxton ; The Canadian Army Dental Corps

While writing “Maple Leaves in Buxton” about the Canadian presence in Buxton during the First World War, in the interests of space I was forced to leave some material out. Among the Canadian medical personnel in Buxton were a number of dentists. While dentistry might not immediately be considered front line military medicine, military dentistry made a substantial contribution in getting men fit enough to get to the front and many Canadian dentists saw frontline service. The Canadian Red Cross Special Hospital, the Granville Special Hospital and the Canadian Discharge Depot in Buxton all provided dental services to Canadian Soldiers. So here is a brief survey of Canadian dentistry in Buxton.

The origins of Canadian military dentistry might be traced back to the Anglo-Boer War in South Africa from 1899 to 1902 where a Canadian contingent operated with the Imperial Forces. The Canadians brought dentists with them, the first time they operated in a theatre of war. Dentists accompanied Canadian Troops in operations in the Transvaal, the Orange River Colony and the Cape Colony. The great number of soldiers who presented with dental emergencies confirmed that dental services in the field were indispensable. At the Canadian Dental Association (CDA) meeting at McGill University in 1902, Doctor Ira Bower of Ottawa presented a paper entitled Dentists in the Army. After the paper the CDA passed a resolution favouring the creation of a regular army dental staff. Subsequently the CDA pressed the government of Canada to form a Regular Army Dental Staff as a distinct branch of the service. This effort met with success when by General Order No 98, dated 2 July 1904, an establishment of 18 Dental Surgeons in the Canadian Army was authorized.

General Order No 63 was issued on 13 May 1915, authorizing the Canadian Army Dental Corps (CADC) as a separate corps. In anticipation of this general order, on 29 March 1915 authorization was published to appoint "one officer in charge of all dental surgeons, to be attached to divisional headquarters …, to be designated 'Chief Dental Surgeon' as well as an establishment of dental officers for brigades, divisions, base hospitals and field ambulances. This provided a war-time establishment for the new CADC, with a Lieutenant-Colonel Chief Dental Surgeon for each division. A few days later Colonel John Alexander Armstrong was promoted, named the Director of Dental Services, and assigned to Canadian Corps Headquarters in London. In 1915 the first Canadian Military Dental Clinic was established in a stable at the Exhibition Grounds in Toronto. This was the first Military Dental Clinic in the British Empire. Dental officers were then attached to the existing medical formations, including Field Ambulance at the Front and became integral parts of the unit; a laboratory was established at corps headquarters as the principal dental depot, where all the necessary appliances were made with incredible speed by dental mechanics. A British Army consultant, Sir Cuthbert Wallace, would later state in 1918 that, “the Canadians had a very perfect dental organization” and suggested that the British service copy the Canadian model which enabled them to provide advanced treatment in the forward areas.

In his history of the Canadian Medical Services, Andrew MacPhail says:

“Good teeth to a soldier in these days of luxurious rations are not so important as they were in times when the only test of food was its hardness. As early as November, 1914, instructions were issued in the English service that no man was to be discharged on account of loss of teeth if by treatment he could be made fit to remain in the service. In January, 1915, men with defective teeth might be attested if they were willing to receive dental treatment; in February a recruit might be passed “ subject to dental treatment.”

It is a very serious point, with may rations consisting of rock hard biscuits going to the front with broken or damaged teeth was likely to lead to serious problems. Likewise, suddenly suffering from severe dental problems in the trenches was likely to prove dangerous.

The Canadians were lucky to have a high proportion of dentists. The United States had one dentist to 2,365 of the population; Canada, one to 3,300; Ontario, one to 2,238; Quebec, one to 6,126; England was far behind with one to 7,014. In England there were many unregistered dentists, but they confined themselves narrowly to the specialty of pulling teeth, with the result “that men had their teeth extracted unnecessarily and were held back from drafts until their mouths were ready for dentures.”

The British sent 12 dentists to France with the BEF in November, 1914; the number was increased to 20 in December; to 463 in December, 1916; to 849 at the time of the armistice. In March, 1918, an inspecting dental officer was appointed to the staff of the Director-General, and he reported that 70 per cent of the recruits required treatment, the number each month being 136,150. For their much smaller Expeditionary Force ,when it began operations overseas in July 1915 the CADC had 30 Dental Officers and 74 other ranks - a ratio of 1 dentist for every 1400 personnel.

In France, the personnel of the CADC carried on their work mainly at field ambulances, casualty clearing stations, general and stationary hospitals, in the forestry units, in the various units of railway troops, and at base camps. These widely dispersed duties were performed under the supervision of the deputy-director of medical services at Canadian corps headquarters, who forwarded reports on all dental work to the director of medical services in London.

In England, clinics were established at the various Canadian training centres, command and discharge depots, special hospitals, and segregation camps; in London for the personnel employed at the different Canadian administrative offices, and for officers and men on leave from France requiring emergency treatment. Every Canadian soldier on arrival in England, while passing the prescribed time at a segregation camp, received dental inspection and, if time permitted, his needs were attended to. If the work could not then be completed, indications for further treatment followed the soldier to whatever camp he might be sent, and there the work was continued. Finally, he was again examined before being placed on draft for France, and either was passed as fit or made so before leaving.

To start with the Canadian Red Cross Special Hospital did not have dental facilities. On 19 December 1916, Captain Herbert Ross was appointed as a dental officer. First he had to acquire some dental equipment from the DDS. On 28th December he arrived in Buxton, shortly followed by Sergeant Oswald Brewer of the CADC. Their dental equipment arrived from London on the 30th. Brewer was born in Louth, Lincolnshire in1891 and emigrated to Canada. He attested for the Canadian Army in Winnipeg on 30 May 1915.arriving in England on 3 July1915, on the SS Missonabie. After a stint at the Canadian hospital at Bramshott, Brewer was sent to France, where he served on the Dental Staff of the 2nd Pioneer Battalion before moving to the dental Laboratory at the Canadian Base Depot in Le Havre. After serving at the front, Brewer stayed as a dental technician in Buxton until 13 September 1918, after moving to London and Witley, he returned to Buxton in September 1919, to the CDD for demobilisation return to Canada.

Captain Ross stayed in Buxton until 15 March 1917, when he was transferred to the HQ of the CADC in London. He was replaced by Captain Alfred James Thomas, a dentist from British Colombia. Captain Thomas remained as dentist at the CRCSH until March 1918.He was replaced by Captain Tait.

In addition to the general clinics which cared for most of the work there were special clinics resembling the one at the International Co-operative Institution at Queen’s Hospital, Frognal, where patients who had received injuries to the nose or chin received the best treatment that medicine and dentistry could provide. By a combination of facial surgery and mechanical appliances injured parts were restored and lost parts replaced, so that the patient was able to chew his food, and his personal appearance was improved. The problem presented by numerous cases of fractures of the jaw became a serious one, and it was necessary to institute a special clinic at the Ontario Military Hospital, Orpington, to deal with this type of casualty, and excellent work was done in restoring to patients the lost function. Previous to the war, many officers and men had been fitted by their private dentists with gold bridges and other dental appliances; in numerous cases these had to be re¬ placed or repaired. To meet this situation, the necessary arrangements were made whereby, at no extra cost to the public, this special work could be done; the patient signed a form which authorized the paymaster-general to deduct from his pay the bare cost of the material used.

From its initial 30 officers. 34 non-commissioned officers, and 40 other ranks in 1914, by the time of the armistice the strength had increased to 223 officers. 221 non-commissioned officers, and 238 other ranks. Of this number 76 officers, 76 non-com¬ missioned officers, and 64 other ranks were in France; with 147 officers, 145 non-commissioned officers, and 174 other ranks in England.

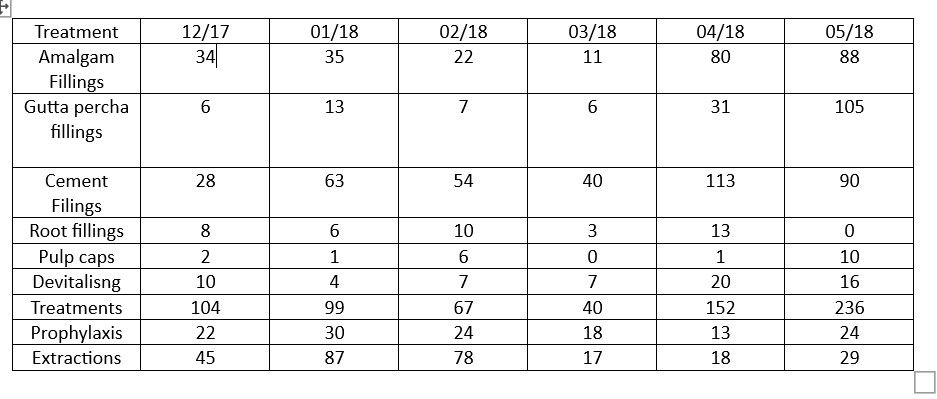

When the Granville Special Hospital arrived in Buxton from Ramsgate, it too opened its own dental surgery. The dental officer Norman Samuel Bailey from Portage La Prairie in Manitoba arrived on 31 October 1917, staying until March 1918, when he returned to the CADC staff. The Granville War diary records the number of dental procedures undertaken on a monthly basis . Bailey was certainly kept busy. Bailey was later assigned to the CADC laboratory in France . where he took part in the campaign of the last 100 days . He went into Germany with the Army of Occupation before returning to Canada, and was attached for a time to the Tuxedo Military Hospital at Winnipeg. He died on 22 December 1961. Bailey was replaced at the Granville, by the young (21 year old ) dentist, Captain Roy Wellington Blackwell, who remained the Dental Officer until June 1919, when he was demobilised and returned to Canada. Below is a list of the treatments carried out by Bailey and Blackwell at the Granville in the six months from November 1917 ( sourced from the Granville Hospital War diary)

The Armistice in 1918 reversed the aim of the CADC. Instead of making men dentally fit for war the corps devoted its activities to making men dentally fit for peace, and every soldier returning to Canada was accompanied by a document giving his exact dental condition at the date of his last inspection before embarkation. The Canadian Discharge Depot Souvenir, contained a description of the dental services provided:

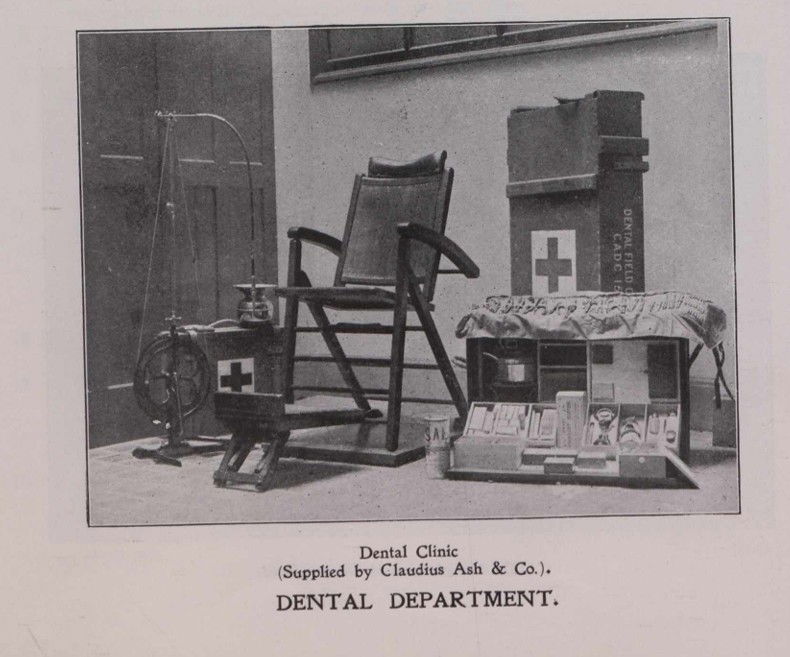

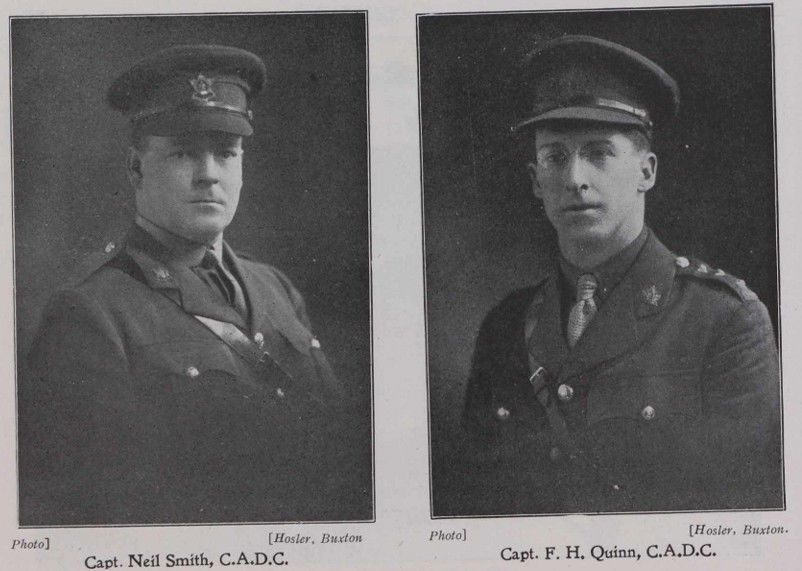

“Always apt with nicknames, the troops passing through the Canadian Dis- charge Depot refer to the Dental Department as -The Chamber of Horrors.»’ One morning recently a neatly written sign was found hanging on the door of the Clinic : " Abandon hope all ye who enter here.” After treatment, and the benefit makes itself felt, a doubt is always expressed as to the correctness of these references, but these impressions remain and always will, so long as soldiers are. The Dental Clinic was opened in June, 1917, by Lieut.-Col. N. Smith. Owing to the large number of men passing through, it was found necessary to enlarge the scope of the Clinic. A second chair was installed, and the services of another officer, Captain F. H. Quinn, obtained. The equipment of the Clinic is the regular Field Service Outfit, consisting of portable chair, engine, and sundries—kit containing all the necessary instruments to deal with a case presented for treatment. Chief among the functions of Dental Clinics is the relief of pain, strange as that may appear, but the man who has suffered agonies with toothache is not slow in expressing in true soldier terms the relief he feels once the dreaded operation is over. An ounce of operation, to quote the Dental Officer, is worth pounds of cure, and the man who has not suffered sleepless nights owing to dental trouble, invariably owes his good fortune to timely visits paid to the Clinic. In the training camps in Canada and England, the Canadian Army Dental Corps is mainly concerned in fitting men for the trenches, getting their mouths in condition to properly masticate their rations, also preventing the possibility of subsequent dental trouble. The Dental Clinic at the Discharge Depot, apart from its emergency and operative work, examines the teeth of every N.C.O. and man prior to his return to Canada for disposal or discharge. This examination is very thorough, and also entails the filling out of a number of regulation documents, replete with the details of any other work required. All the work on a man’s mouth is done without cost to himself, gold work being supplied in cases of wounds or injuries directly war. Whenever possible the patient has the whole of his dental troubles completed before leaving for Canada, but it will be readily understood that owing to the short period of stay it is impossible to complete all the work presenting itself. In any case the man's mouth is put thoroughly at ease, and to ensure completion, a document accompanies the man showing the work necessary to be done. Thus it will be seen that a man can leave the army with his dental condition in as good or if better shape than when he left his civilian occupation. Many men have expressed their sais faction in no uncertain terms. Every war produces its own particular horrors and among those produced by this war is the disease commonly known as trench mouth. A technical description of this disease cannot be given here, but in a few words it is a rapid ulceration and sloughing of the gums, lining membrane of the cheeks, throat and tonsils, and if allowed to run its course will cause great destruction of tissue, and the teeth become so loose that extraction is the only remedy. The acute stage causes such severe pain that the Patient is unable to cleanse the teeth or even masticate food, the result being loss of sleep and the consequent debility. Fortunately, as a result of insistent research by the Canadian Army Dental Corps, it is now possible to give immediate relief and by a series of daily treatments a cure is effected. If the disease is discovered in its early stages, the condition is quickly controlled. Owing to a predisposition to recurrence it is essential that the patient keeps his mouth and teeth in a thoroughly clean condition”

Neil Smith, a dental surgeon from Chatham, Ontario had enlisted in August 1915, and held rank of Major in 70th Battalion. In January, 1916, he was promoted Lieut.-Col. and recruited and organised 186th Battalion, in Kent County, and Chatham, Ontario, recruiting a strength of 18 officers and 469 other ranks. The battalion embarked from Halifax on 28 March, 1917, on the troop ship Lapland, and disembarked in the UK on 10 April. Although he had not signed up for the dental service, he was assigned to the CADC , having served in France in Fall 1917, he transferred to the CDD in February 1918, by then with the rank of Captain in the CADC.

Smith’s colleague , Captain Francis Hawksworth Quinn was born in 1882 in Formby, Lancashire and emigrated to Canada. He attested in Vancouver on 20 March 1916 and was taken on the strength of the CADC in January 1917, passing through Canadian facilities in Brighton , Seaford and Crowborough before being sent to the CDD on 7 September 1917. He stayed until 2 August 1918, when he went to the Front in France with the 4th Canadian Casualty Clearing station, where he served at the Front during Canada-s 100 days , After his service at the front, Quinn returned to Buxton to the CDD to be discharged, returning to Canada in December 1919.

Quinn’s successor Captain Harold Cowan, was from Regina, Saskatchewan where he was appointed May 7th, 1917. Officer i/c Dental Services to returned soldiers for Saskatchewan. Resigned to proceed overseas, and was attached to the 15th Reserve Battalion for duty arriving in England in march 1918 Later transferred to the 12th Canadian Military Hospital at Bramshott and was detailed from there to C.D.D. staff.

The book on Canadians in Buxton

Maple Leaves in Buxton, by David Roberts

Service records of Dental Staff who served in Buxton- links to the Canada Archives records

Captain Herbert Ross

ROSS, HERBERT (3 digital object(s)) Genealogy / Military / First World War Personnel Records

Captain ( Lt Colonel ) Neil Smith

SMITH, NEIL (2 digital object(s)) Genealogy / Military / First World War Personnel Records

Captain Francis Hawksworth Quinn

Captain Norman Samuel Bailey

BAILEY, NORMAN SAMUEL (2 digital object(s)) Genealogy / Military / First World War Personnel Records

Captain Roy Wellington Blackwell

Captain Harold Cowan

COWAN, CANADA HAROLD (2 digital object(s)) Genealogy / Military / First World War Personnel Records

Sergeant Oswald Brewer

BREWER, OSWALD (3 digital object(s)) Genealogy / Military / First World War Personnel Records