The 60th Rifles-Harry Hastings and the Wreck of the RIMS Warren Hastings

Born on 13th January 1876 at 17 Ordnance Road, Isleworth, Great - grandfather , Harry Percival Hastings lived his early years in Hounslow, where his father Henry Hastings was in service at nearby Osterley House. Early in 1891, he had managed to enlist as an underage soldier in the British Army. Under the Army Enlistment Act 1870, Harry was initially engaged to serve 12 years in the infantry; however with the first six years spent with the colours and the remainder in the first class Army Reserve. After enlistment, the Army sent Harry to join the King’s Royal Rifle Corps at the Rifle Depot in Winchester, Hampshire. When Harry arrived at Winchester, the Commandant of the Rifle Depot was a long-experienced rifle officer Colonel George Hatchell.

Following his basic training at the Rifle Depot, Harry was sent to join 2nd battalion KRRC at the Richmond Barracks in Dublin until 1 December 1991 when he set sail for Gibraltar arriving on 8 December 1891. On 13 January 1895, the Battalion sailed for Malta[1]. The 2nd Battalion KRRC arrived in Malta on 17 January 1895 from Gibraltar on the troopship Victoria and was accommodated at the Notre Dame and Floriana barracks. The battalion stayed uneventfully in Malta for eighteen months and left by way of the Suez Canal for South Africa on 16 July 1896 arriving at Cape Town on 5th August 1896. After six months in South Africa with the 2nd Battalion, Harry was ordered to join the 1st Battalion of the KRRC which was due to sail at the end of December for Mauritius

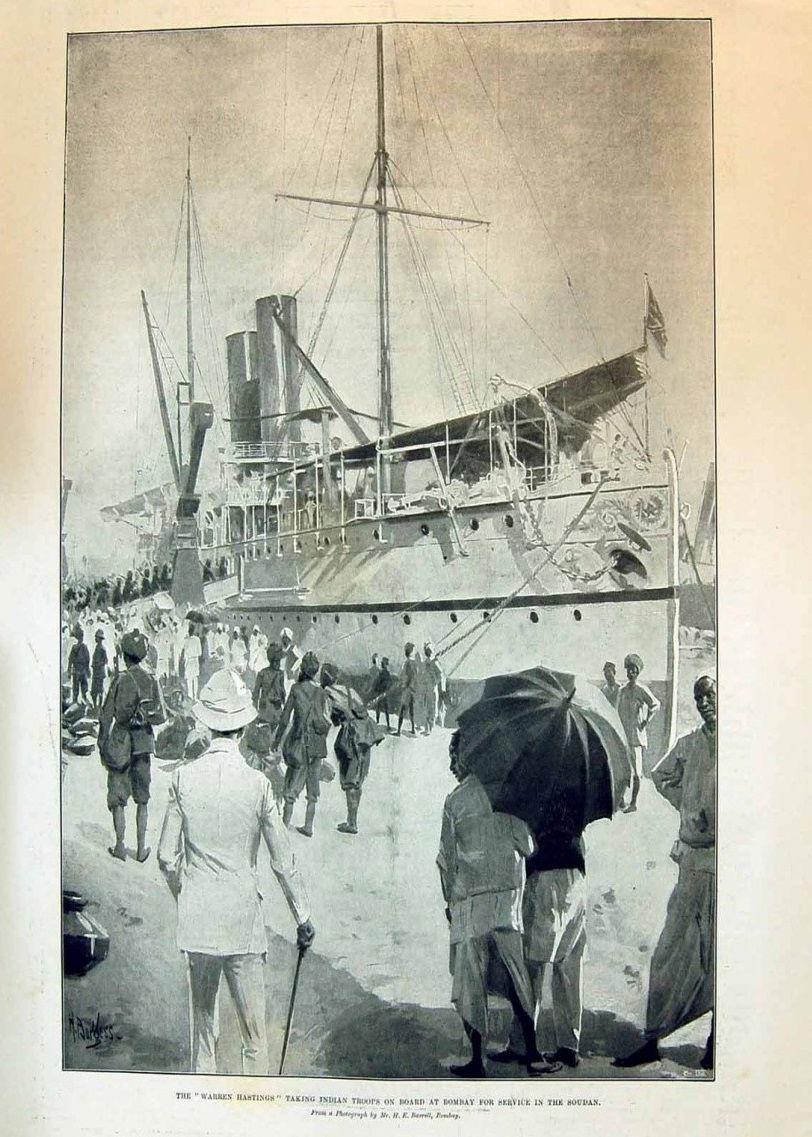

The 1st Battalion which had served for several years in India had set sail bound for the Cape on 10 December 1896. The Battalion, under the command of Lt Col M. C. B. Forestier-Walker had set sail from India on the RIMS “Warren Hastings” (Commander G E Holland DSO, RIM). Arriving at Cape Town on December 28, B, D, E and F Companies commanded by Major R H Gunning disembarked and the ship was to continue its journey for Mauritius on 6 January 1897 with the Headquarters and A, C, G and F Companies of the 1st Battalion KRRC, a half Battalion of the 2nd York and Lancaster Regiment and 25 men of the Middlesex Regiment. Seventeen wives and 10 children were also on board. The total number of troops on board was 22 Officers, four Warrant Officers, 940 noncommissioned officers and men, four ladies, 13 women, and 10 children. The route to Mauritius took the Warren Hastings from Cape Town across the Indian Ocean and then past the tip of Madagascar and Reunion. In an inauspicious start on the 6 January , the Warren Hastings was unable to get out of the docks because of strong winds, but the next day it finally managed, although the weather continued to be bad.

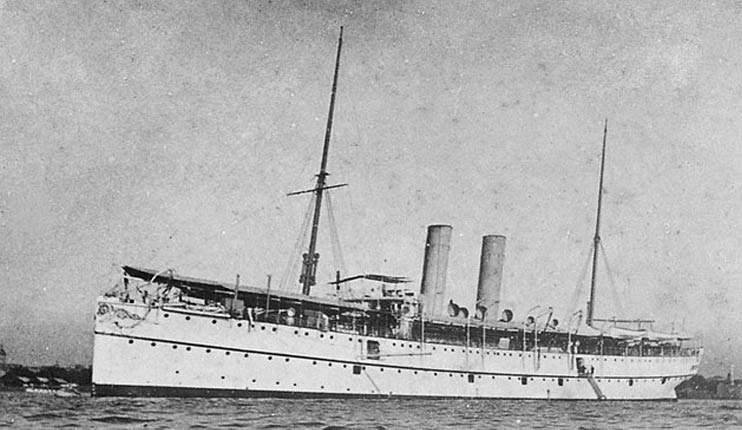

The RIMS Warren Hastings

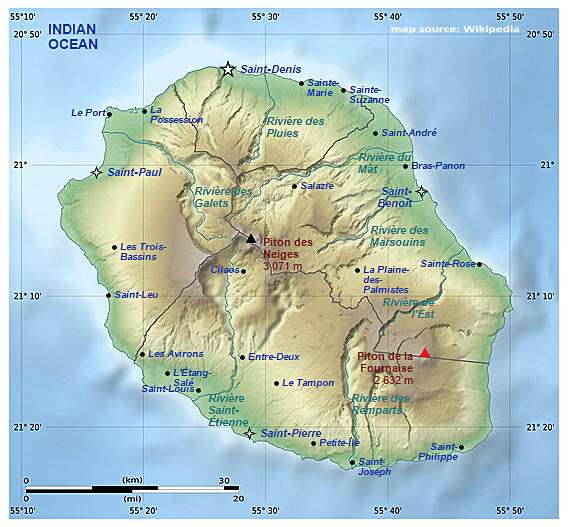

When they set off from Cape Town , the authorities and the crew on the Warren Hastings were unaware that on Reunion, the Piton La Fournaise volcano had began to erupt on the eastern side of the island. Piton La Fournaise , known locally as Le Volcano , was and still is one of the most active volcanoes in the world, with more than 150 recorded eruptions since the 17th century. Most eruptions of Piton de la Fournaise are of the Hawaiian style: with fluid basaltic lava flowing out with fire fountaining at the vent rather than large eruptions ., being on the eastern side of the island, the volcano was far removed from the route of the Warren Hastings, although an eruption had the potential to disrupt the readings on the ship’s compasses.

The RIMS Warren Hastings was designed by Sir Edward Reed and constructed at the Naval Construction and Armaments Company in Barrow-in- Furness. The vessel was 350 feet long, with a breadth of 49 feet and displacement of 5008 tons. She was fitted with twin screws and triple expansion engines capable of reaching 17 knots over a measured mile. Steam was provided by 8 boilers of the latest type and the bunkers held 674 tons of coal. At an average speed of 10 knots per hour, the Warren Hastings could go for 30 days without recoaling. Her interior fittings were very up to date, and she was specifically designed to carry troops in hot climates, with numerous innovations to keep cool air circulating. The accommodation for 1,100 troops was located over three decks. The spar deck contained the deckhouse and the usual necessities for running the ship and included a splendid stretch of deck over three hundred feet in depth on which the troops could exercise. On the second deck (the orlop or waste deck) there was accommodation for military officers, ship’s officers, ladies quarters, a roomy saloon which seated 48 people and extra space for troops. The lower deck was for accommodating troops. The ship was entirely lit by electric light and in short was roomy, well aired and well appointed. For safety the hull was divided into seven watertight compartments and there were 10 lifeboats plus 6 collapsible boats.

In 1894 HW Brent, Director of the Transport at the Admiralty had raised doubts about the carrying capacity of the Warren Hastings. He considered it should not carry so many as 1,072 on the voyage between England and India. Brent was not favourably impressed with the orlop deck accommodation and would have preferred the use of the lower troop deck for accommodation only, limiting capacity to 755 men. If it was necessary to use the orlop deck, no more than 100 men should be accommodated there. However, on 22nd August 1895, Major General O R Newmarsh, the Military Secretary wrote to Brent saying that the Warren Hastings “ compares favourably with the Indian Troopships in the matter of light and ventilation “ and its capacity was therefore set at :

- Main deck in hammocks 560

- Main deck in guard beds 225

- Lower Deck in hammocks 206

- Lower Deck in guard beds 81

- Total 1,072

The 1st Battalion KRRC had embarked for India in HMS Crocodile on 25th November 1890. On the outbound voyage HMS Crocodile had broken down and after a period drifting in the Indian Ocean had been picked up and towed to Bombay by her sister ship HMS Serapis. The Battalion disembarked in Bombay on 27th December 1890 and after a few days acclimatization at Deolali, they had moved up country by train. The train journey was undertaken largely at night and days were spent at rest camps at Kandwah, Hoshangabad, Jhansi , Tundli and Umballa ( where the battalion was reviewed by General Sir Frederick Roberts, the Commander- in- Chief India. Finally, they arrived at Rawalpindi. In 1891 the Battalion participated in the Hazara Expedition, as part of the Reserve Brigade under Brigadier-General Sir William Lockhart and had marched out of Rawalpindi on 27th March 1891. The march had been a hard one and still in their early days in India, many men had collapsed from heat-stroke. At the time both the officers and men lacked experience, those few officers with past experience had mainly served in the different circumstances of Southern Africa. By the time they reached Durband, the threat from the Bunerwal tribesmen had subside and the battalion were left idle for a few days. It was not long, however, before further trouble broke out among the Orakazi tribesmen in the same area. The Reserve Brigade was ordered to march from Durband to Kohat , which they reached on the 12th and then on to Chilibagh and Hangu where they joined the rest of the Brigade. By this time the soldiers were in better condition, and few suffered from heatstroke on the way. On the 17th the Battalion formed part of the column which climbed up from Hangu to the ridge at Lakka, this was a particularly strenuous day- climbing steep gradients in the fierce sun and with minimal water supplies. As they marched along the ridge they came under fire from a rebel stronghold at Tsalai and Colonel Cramer and three men were slightly injured. The rebels pulled out of Tsalai and the battalion went on to join up with the rest of the column at Sangar. They lost one man to an enemy sniper on the way. By 24th April the Orazaki tribesmen approached the British to seek terms and the accepted the conditions the British imposed. The Battalion had suffered minimal casualties and was now proving to be an effective force on the frontier.

In January 1892, Lt Colonel Benjamin McCall assumed command of the Battalion following Colonel Cramer’s retirement. Later in 1892, the Rifles were sent to suppress a further outbreak of tribal unrest when a banished tribal leader Hashim Ali from the Isazai Clan returned to foment revolt. Again the British launched a punitive expedition , the Isazai Expedition and a half Battalion of the Rifles from Rawalpindi participated. This expedition amounted to little as the tribesmen put up little resistance and evacuated the disputed territory. There was then a period of quiet which the battalion spent at Rawalpindi and Peshawar until in 1895, they took part in their last expedition on the NW Frontier, the Chitral Relief Force.

The officer commanding the RIMS Warren Hastings, Commander Holland, was born in Dublin in 1860, and educated at Ratcliffe College, in Leicestershire, he had joined the Royal Indian Marine Service in 1880 and was promoted to Lieutenant in 1882. He had served with Burma Expeditionary Force, 1887-89 (medal, 2 clasps); in the Chin Lushai Expedition, 1889-90 where he had been mentioned in dispatches and awarded in the Distinguished Service Order. Ever since, the annexation of Upper Burma in 1885, the British had been struggling with the Chin Hill tribes on the border between Bengal and Burma, the only options were to try and bring the area under British rule- Key to success was the transport and supply for the expeditionary force. Supplies could be bought a certain distance up the Kalemyo River but another uncharted river, the Myitta went still further into the disputed area. Commander Holland was directed to explore the Myitta River and determine whether it was navigable or not. When he reported that it was, he was directed to set up a boat service to bring supplies upriver, contributing to the success of the British mission. The other officers serving with Holland on the “Warren Hastings” were Lieutenant Walker, Lieutenant Ernest Huddleston and sub-Lieutenant Walter Windham.

The troops were under the charge of Colonel Montague Charles Brudenell Forestier-Walker was born in 1853, the son of a General. He had been commissioned as a Lieutenant in the 60th Rifles on 6th March 1872, he had served in the Bechuanaland Expedition in 1884-5 as Aide – de-Camp and Acting Military Secretary to Sir Charles Warren ( where he had been mentioned in dispatches). He had then served with Burmese Expedition in 1891-92, in the Chin Hills as an Intelligence Officer and in the Lushai Column. Most recently he commanded the 1st Battalion KRRC in the Chitral Relief Column. Of the other Army officers on the “Warren Hastings”, Major Gore-Browne had served with both the Miranzai and Isazai expeditions and with Forestier-Walker in the Chitral Relief Force. Both Captain Pechell and Captain Dwane, the battalion Quartermaster had served in all of the NW Frontier engagements, Hazara , Miranzai and Isazai and with the Chitral Relief Force. Captain RM Stuart-Worley had arrived later on the scene and had served with the Relief Column. Captain Prendergast has transferred from the 3rd Battalion where he had served in the 1884 Sudan Expedition and the engagement at Temai. Lieutenant Cumberland served in Isazai and with the Relief Force, while the two more junior Lieutenants John Taylor and Bernard Majendie had been commissioned in March 1895 and January 1896 respectively and so had missed out on the earlier engagements. The men from the 2nd Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment were commanded by Major Kirkpatrick,

Many of the men on board the ship had served with Colonel Forestier-Walker in the Chitral Relief column of 1895 and after their period on the North-West frontier of India, must have been looking forward to a posting to the tranquil island of Mauritius.

The Warren Hastings set off from Cape Town , with the ship and it’s troops under the command of these two distinguished officers. The first seven days of sailing were uneventful. After the difficulties with the SE gale blowing when they tried to leave Cape Town , the weather was fine, although on the morning of the 13th the Barometer began to drop, the weather became unsettled, and the wind rose to a Southerly Force 4 to 6. By the morning of the 13th the sun had become obscured and observations of longitude could no longer be made. By midday the sun had come out again and at 3pm , the ships position was fixed at Latitude 22, 39 22S and Longitude 53° 33’ 50 E- which was the mean of the observations of Holland and the Navigating Lieutenant. A course was set for N64°E, and then adjusted to N63°E, the vessel was proceeding at a rate of 12.5 knots, with a southerly wind of force 3 to 5. Conditions were generally overcast and at about 2 am, torrential rain started.

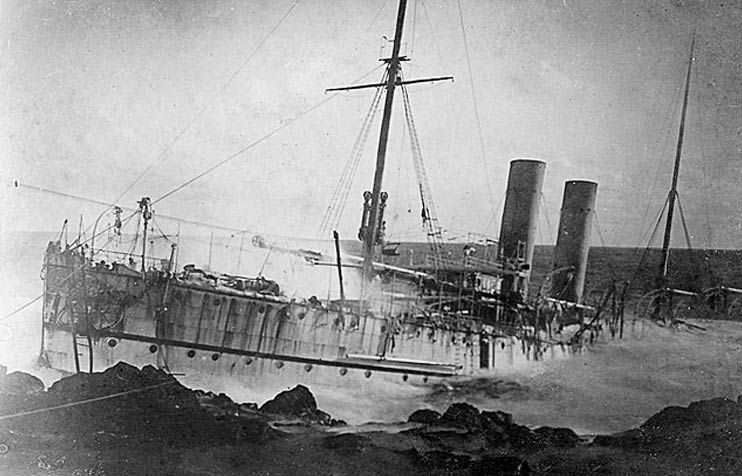

On the bridge at 2 am were Commander Holland, Lieutenant Walker the navigation officer and Lieutenant Windham, the Officer of the watch. According to the dead reckoning, their position at this time, should have been latitude 21° 29’ 12 S and Longitude 55° 46’ 12 E which was about 8.1 miles S 4 ½ ° W of where it actually was. The darkness was intense and to the men on the bridge, land appeared to be about 1 ½ miles away. Commander Holland was absolutely sure of the correctness of his position, from the soundings taken at 3pm and by the fact that the high mountains of Reunion were in the distance. He, therefore, did not consider it necessary to proceed at a slower speed, for apart from the intense darkness and heavy rain there was nothing to concern him about the ship’s position. At 2.20 am, without any warning the ship struck the rocks at 12.5 knots. The engines were immediately stopped and reversed, but as he did this Holland realized that the vessel must be on the South Coast of Reunion with very deep water astern and therefore, it was safer to keep the engines going and try and force the ship as high as possible up onto the rocks.

During the night of the 13th and 14th January, the soldiers sleeping on the lower deck felt a sudden jolt and some were thrown from their hammocks, some made their way to the portholes, there was torrential rain falling and it was impossible to see much, but it was pretty clear that the ship had run aground. The sea at the time was calm, though there was a moderate swell. The engines were still working at full speed ahead, and were kept so until stopped by the water. Some of the men being awakened by the shock, were about to make a confusion by running up on the top deck, when they were ordered to bed. Lance-Sergeant Alfred Addyman and another Lance Corporal told them that it was alright, the ship had landed, and that it was only the anchor that had been dropped, this satisfied the men for a while, but when they saw the ships carpenters taking soundings of the wells, and screwing up air tight compartments they knew we the ship was on the rocks, but all kept calm, and waited for orders, and in the meantime steadily dressed, the best way they could, in total darkness. As the ship was being bumped up and down on the rocks, in the increasingly high seas, the men were ordered to advance on to the next deck, called the waste deck, Here the men fell in and were packed like herrings, waiting in some anxiety for further orders. Captain Stuart-Wortley roused from his sleep encountered Lieutenant St John who said he thought that the propeller must have broken, but after several more bumps realized that they must have run aground. Writing later from the safety of Mauritis, Sergeant Addyman described the events (Thomas Alfred Addyman was a 19 year old cloth worker from Leeds when he enlisted in the KRRC at Pontefract in February 1990. He served for six years in India and later served in South Africa at Talana, Ladysmith and Laing’s Nek)

“We got out of the docks and put to sea, weather rather bad, but everybody in good spirits, and in hopes to finish the voyage, everything goes well, until the night of the 13th inst, when we were passing the Isle of Re-union, the weather becomes bad, the night is as dark as pitch, and rain falling in torrents, impossible to see anything. I retired to my hammock, after getting wet through above, and feeling cold and just then miserable. I could not sleep. I was thinking of everything, first that we should land alright at Mauritius at 2 pm tomorrow, then we would be able to get comfortably settled down once more. At 2-20 am, the ship gave a terrific shock from stern to stern, which threw me out of my hammock, as I was only lying on the side of it, to the deck. I got up and looked through the port hole, and could see, we were stopped, and a great rock a few yards in front, the water beating violently against the side of the ship he men being awakened by the shock, were about to make a confusion by running up on the top deck, when they were ordered to bed. I and another L/Cpl, who had our hammocks together, told them that it was alright, as we had landed, and that it was only the anchor that had been dropped, this satisfied the men, but when they saw the ships carpenters taking soundings of the wells, and screwing up air tight compartments they knew we were on the rocks, but we all kept calm, and waited for orders, and in the meantime steadily dressed, the best way we could, as we were then in total darkness, afterwards the ship was being bumped up and down on the rocks, by the high sea running, then came the order to advance on to the next deck, called the waste deck, this is also covered in, we fell in on this deck, and were packed like Herrings, we waited about one and half hour, and the anxiety was tremendous, but we calmly waited for orders.”

Commander Holland ordered all of the ship’s watertight doors to be closed and the life boats to be cast loose and made ready for lowering. Soundings were taken from all around the boat, which confirmed that the seas around were between 4 to 8 fathoms in depth. At 2.45 am, Holland sent Lieutenants Walker and Windham forward to review the situation and they reported that the rock against which the ship’s bows were resting appeared to afford landing space, Commander Holland, at 3.15 a.m., sent Lieutenants Dobbin and Windham, R.I.M., down over the bows, with blue lights, to investigate whether the rocks were suitable for men to land- they reported that it was.

Meanwhile, Commander Holland had summoned Lt Colonel Forestier Walker onto the bridge. He arrived together with Captain Richard Montagu Stuart-Wortley, the Adjutant. Orders were then sent for all troops to leave the upper deck, to leave room for the crew. to land there and he gave orders that the men should be formed up by regiments, the King’s Royal Rifles on the port side and the York and Lancaster and details on the starboard side of the ship, so that the two forward companions could be used simultaneously. Up to this time, though the vessel was bumping heavily, she was lying on a fairly even keel, and Commander Holland therefore considered that the disembarkation of the ladies, women, and children could with safety be deferred till daylight, as it could then be carried out with so much more safety and convenience to them.

Orders were issued for the disembarkation of the men to commence 1/2 hour before day break, the men were ordered to go down and get properly dressed, and save what they could, however, in the darkness and with the lower decks rapidly filling with water it was impossible to get anything, and they went back to the waste ( orlop) deck to await final orders. At 4 a.m. disembarkation commenced using rope ladders on either side of the bow. However, on the waste deck, the situation was deteriorating, and the ship was now in danger of capsizing. The men on the starboard side, which was quickly filled with water were first to be moved on to the top deck, and landed by the best of means, the port side was now at an angle of 50 degrees, the companion ladder being right over, made it very difficult to climb, one man nearly fell off, and if he had he would have gone rolling to the starboard side, and certainly gone into the water, and would have been washed away through the iron gangway broken open by the water, but he managed to hang on to Lance-Sergeant Addyman nearly pulling him down.

Addyman held on like grim death to the ladder and managed to get on the top deck, which being very slippery he went sliding with speed from the Port to the Starboard side. He managed to save himself by grasping the hydraulic lift from going into the sea, as the starboard side was all in the water and it was above the rails. About 4.55 a.m., Holland gave permission to men who were good swimmers to drop off and swim ashore on the port side, a distance of some 30 yards, and the first man who did so, Private McNamara, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, was successful in carrying a line to the land, by aid of which some three or four ropes were carried and made fast, and were the means of assisting a considerable number of men to the shore. The men went down them hand over hand all the way to the shore. Laboriously, they pulled themselves hand over hand along the rope hanging on for dear life as the waves crashed over them. As they reached the shore and they were pulled ashore by willing hands, who said, “that‘s another one safe and sound”. The Adjutant was handing round a jar of spirits around the men which at least bought some warmth and life back to them. Addyman caught a pair of boots thrown off the ship, which but they were too small, he improvised by cutting a whole in the front to enable him to get his feet into them, although better than nothing he still cut his toes, which protruded over the soles.

All around , were deeds of heroism from men of the 1st Battalion KRRC .Private Miles Arrowsmith was already on the rocks near the bow of the ship, when a child of one of the York and Lancaster Regiment, who was being brought down the ladder, slipped and fell into the sea, Arrowsmith, although unable to swim, jumped in with a rope and was pulled out again with the child in his arms. (Arrowsmith was a moderately unlikely hero. Born in Preston in 1873 he had enlisted in the KRRC in January 1891, within three months he had been imprisoned for assaulting a fellow soldier. Imprisoned twice in India for drunkenness , he served in the Chitral Campaign of 1895. For his heroic actions during the wreck of the Warren Hastings, he received the Royal Humane Society Silver medal. He later served in South Africa at Ladysmith, Laing’s Neck and Tugela Heights.)

Private Carr swam out some distance to the assistance of Mr. Gadsden, R.I.M., chief engineer of the ship, and brought him ashore. Private G. Howes, at the time a patient in hospital, dived in and attempted to save a native cook, who was drowned. He had afterwards to be himself helped out of the water. “Though the swell at the time was only moderate, the waves were breaking on the rocks with considerable force and the backwash was sufficient to prevent anyone landing without assistance, and groups of men were all along the shore helping others as they came near. on to the rocks. “ Lance Corporal Richard Newby of the 1st Battalion KRRC dived from the ship and assisted a man from the Ypork and Lancaster Regiment to a rope by which he was got ashore.( Lance Corporal Newby ( 7291) a printer by trade from Everton, Liverpool attested for the Kings Royal Rifles in Liverpool on 17th March 1892, aged 18 years 3 months. He served in India from 8th December 1893 , until he set sail on the Warren Hastings, then in Mauritius until March 1899, when he was transferred with the 1st Battalion to South Africa- He served during the Boer War in Natal and Transvaal and was discharged from the Army on the 16th March 1904. Newby was awarded the Royal Humane Society Medal for his gallantry on the Warren Hastings )

Private William Grisley swam out with a buoy to the assistance of Private J Brown also of the 1st Battalion by which Brown was saved. Private Levi Augustus Wootton swam out to assist Private G Taylor and after bringing him ashore , went in again and swam out with a buoy to Private Danner who was becoming exhausted . Private Danner missed the buoy and Private Wootton supported him to the rocks. (Private William John Grisley ( 5680) , a Carpenter from Clerkenwell in London attested for the King’s Royal Rifles at London on 29th May 1890. He served in India during the Hazara and Miranzai Campaigns. He gained his 3rd Class School Certificate in November 1893 and took a course of Gymnastics at Umballa in April 1895. Grisley was mentioned for Gallantry on the Warren Hastings . He was discharged in 1897 but rejoined the Colours and served with the 3rd Battalion in South Africa. Levi Augustus Wootton was a groom from Old Bradwell, Stonet Straford Bucks who attested for the King’s Royal Rifles on 23rd June 1891 at Northampton.)

Mr. Tyler, Bandmaster, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, was in the water, on the starboard side, and unable to make any headway against the backwash of the waves, or to get near the shore; Lieutenant Gosling, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, endeavoured to reach him, but after going some 20 yards was washed back, thrown on the rock and injured. 2nd Lieutenant Forman, Royal Artillery, at once went in with a rope and a life-buoy, and swimming out to Mr. Tyler, gave him the buoy. When, however, the men on the shore began to haul on the rope, it parted. 2nd Lieutenant Forman stayed with Mr. Tyler, and Lieutenant Gosling then made a second attempt to reach him, but failed and was brought ashore. 2nd Lieutenant Bayley, York and Lancaster Regiment, then swam out with a rope, and the whole three were then brought close in to the shore, when 2nd Lieutenants Forman and Bayley were hauled up on the rocks, over which the sea was then washing. In endeavouring to pull Mr. Tyler in the buoy slipped, and the backwash carried him out at once. Just at the time one of the boats belonging to the ship, which had washed loose, was drifted sufficiently near the rocks to be got hold of, but was all the time being dashed against them, and actually, being broken up. It was caught and manned by Colour. Serjeant Jones, who was at the time a hospital patient, on board were also Serjeants H. Howarth and R. Down, Corporals R. Hodgson and C. Young, and Privates, W. Parkinson,. G. Kaley, , T. Jones, , J. Connell, , T. Steele, P. Pickersgill, all King’s Royal Rifles. They attempted to be row out to the exhausted Mr. Tyler. Not being able to get the boat out, Sergeant Down dived from the stem and swam to him, supporting him till he could be got on board; but the sea afterwards swept him out of the boat and he was pulled in again by Corporal C. Young and No. 6231, Private C. B. Jones, and was eventually landed in safety, though insensible, together with the crew of the boat. Meanwhile 2nd Lieutenant Selous of the York and Lancaster Regiment jumped overboard on the starboard side and assisted a man to shore who at the time was sinking and who almost certainly would have drowned had he not been helped. Selous then saved another man on the port side, by jumping into the sea and holding him until a rope was thrown to them and they were both pulled on shore. One of the rescued men was Drummer John Higgins of the York and Lancaster, Selous was unable to identify the other. While these dramatic events occurred at sea, two men of the York and Lancaster Regiment bravely remained at their posts.

Private John Norton Roe ( 3879) from A Company was on guard at the time of the wreck as a sentry on the lower deck and staid at his post until the water was over his knees and he was ordered to leave by Lieutenant Bayley. Similarly , his comrade Private Thomas Flannery ( 3631) also from A Company who was on guard over the fresh water tanks remained at his post until the water was over his knees, ieutenant Windham and Sub-Lieutenant Huddleston, were instrumental in saving several lives, including Lance-Corporal Robinson, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifle Corps, who was saved by them both; and Private Diamond, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, whom Sub-Lieutenant Huddleston saved, being afterwards himself dashed insensible against the rocks, and picked out of the surf by Sergeant J. Allen and No. 7030, Private C. Croft, both 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, at great risk to themselves. In his report on the shipwreck, Forestier Walker recognised actons by the following men

1.) No, 7679, Private N. McNamara, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, was the first man to attempt to swim to the shore on the port side, as has already been mentioned carrying a light line, by means of which ropes were carried over and made fast, thus enabling many men to escape.

(2.) No. 6168, Private E. Carr, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, swam out some distance to the assistance of Mr. Gadsden, R.I.M.,chief engineer of the ship, and brought him ashore.

(3.) No. 4421, Private G. Howes, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, at the time a patient in hospital, dived in and attempted to save a native cook, who was drowned. He had afterwards to be himself helped out of the water.

(4.) No. 7291, Lance-Corporal R. Newby, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, dived from the ship and assisted a man of the York and Lancaster Regiment (name unknown) to a rope, by which he wasgot ashore.

(5.) No. 5680, Private W. J. Grisley, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles,swam out with a buoy to the assistance of Private J. Brown, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, by which he was saved.

(6.) No. 6131, Private M. Arrowsmith, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, was on the rocks near the bow of the ship, when a child of one of the York and Lancaster Regiment, was being brought down the ladder, slipped and fell into the sea, Private Arrowsmith, although unable to swim, jumped in with a rope and was pulled out again with the child in his arms.

(7.) No. 6547, Private L. A. Wootton, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, swam out to the assistance of Private G. Taylor, 1st Bn.King’s Royal Rifles, and, after bringing him ashore, went in again Wootton then supported him to the rocks.

(8.) Lieutenant Windham and Sub-Lieutenant Huddleston, R.I.M., were instrumental in saving several lives, but I have been unable to get particulars, except in the case of Lance-Corporal Robinson, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifle Corps, who could not possibly have got ashore but for assistance, and who was saved by them both; and Private Diamond, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, whom Sub-Lieutenant Huddleston saved, being afterwards himself dashed insensible against the rocks, and picked out of the surf by Sergeant J. Allen and No. 7030, Private C. Croft, both 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, at great risk to themselves.

Two officers, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, were ordered ashore, Major Harold Gore Browne, was to land with the men and take command on shore, the other, Captain Gerald Prendergast, whose excellent knowledge of French was likely to be of good service, to proceed to the nearest village and try and make any arrangement possible for the reception of the ladies, women and children, and men. The disembarkation continued.

At 4.20 a.m., owing to the list increasing, Commander Holland had deemed it necessary that the ladies, women and children, and such sick as required assistance, should be landed at once, and for this purpose suspended the disembarkation of the men till it was satisfactorily completed. By this time the sea was beginning to wash over the upper deck on the starboard side, and the men were all moved over to the port side of the ship, Commander Holland considered that she was now in imminent danger of keeling right over and probably sinking in deep water and, it became necessary to expedite the disembarkation, and orders were therefore given to discard both rifles and boots; this order was the more necessary as it was impossible to move along the deck without using both hands to support oneself.

At around, 4.35 a.m., the electric light which had continued working after the wreck finally gave out, but fortunately it was almost daylight and the evacuation proceeded unhindered. The disembarkation of the troops was completed by 5.30 a.m. At this time Commander Holland requested Lt Colonel Forestier- Walker to leave the bridge, so he could go ashore and command the men. The most perfect discipline had been maintained throughout; everyone fell in quietly when the order was given, and remained awaiting further orders, without noise or any sign whatever that anything more than usual was expected of them. Since the great majority of the men were below decks at the time, and could not see, though they could not but be conscious of the danger in which they were, the order maintained appears the more praiseworthy.

When the disembarkation of the men was stopped to allow the ladies, women and children to get ashore, the former quietly stood on one side to permit them to pass, and then resumed their own disembarkation in perfect order, when, all the time, it appeared to be a question of moments when the vessel would heel over. Addyman described the scene around daybreak ù

“Daybreak. Still on the waste deck, the water more furious, the ship is going over, now comes the most trying ordeal that can ever happen in a man’s life, being closed in, with hundreds, and seeing the water rising and breaking iron doors, as if it were matchwood, the men on the starboard side, which is quickly filled with water are first to be moved on to the top deck, and landed by the best of means, then comes the order for the port side of which I am on, to move above, the deck is now at an angle of 50 degrees, the companion ladder being right over, makes it very difficult to climb, as I was climbing a man nearly fell off, and if he had he would have gone rolling to the starboard side, and certainly gone into the water, and would have been washed away through the iron gangway broken open by the water, but he managed to claim hold of my foot and nearly pulled me down. I held on like grim death to the ladder and then he did the same, but managed by it to pull one of my shoes off, which I lost. I got on the top deck, and being very slippery and at an angle of 50 degrees, I went sliding with speed from the Port to the Starboard side. I just managed to save myself half way by grasping the hydraulic lift from going into the sea, as the starboard side was all in the water and it was above the rails. I then threw my other shoe away, as I could not stand in it, it was too smooth and slippery. I find now, being in my stocking feet I can climb up the deck, and now grasp and cling to the Port side rails and riggings, ropes are now taken ashore, and the men are going down them hand over hand and getting ashore. I get on to the boom and help the men, until I was nearly sent flying off that into the water, and unfortunately I cannot swim a yard, so some men, seeing me, said, “come along Corporal, it is your turn now and probably you will get knocked off the boom”. I said, “you go first and I will follow”. but they would not listen. It is feared now the ship will slip off the rock, and will go immediately down to the bottom, in the water, which is very deep. Orders are now given that any man who can swim ashore can do so, and the others to be calm and get off the ship as best as they can. It is impossible to land them by the boats, as they would be smashed to pieces on the rocks. I now lay hold of the rope with my hands, and went sliding down into the water, it was a terrible drop, my shoulders and head are just out the water. I find it is very hard climbing hand over hand on the rope, you are assisted a little when the wave comes in, but it is terrible hard work to hold on when it returns, it is so strong that you have to hang on to the rope with superhuman efforts, landed and pulled ashore by willing hands, who said, “come along Corporal, that‘s another one safe and sound”. I feel very faint and go up the rocks a little to rest, the rocks are terrible, the worst I have even seen for sharpness, they are cutting my socks and feet to pieces. I now have had a rest and witness many gallant deeds of saving life done. I now return to the ship and assist in the best way I can, the Adjutant who was there with a jar of spirits seeing me, called me, and gave me a keg, which put life and animation into me, then I began assisting to hand about the baggage we were saving, we are now ordered to leave the ship, as it is feared she will totally collapse, a pair of boots are thrown off the ship, which I promptly seize, they are too small being 5’s, but I cut the front to enable me to get my feet into them, it is now better than being wholly on my bare feet, but they are painful, as every step I take I cut my toes, which are protruding over the sole, with the rocks, but wrecked men cannot be choosers, so therefore I must contend with it.”

Meanwhile Captain Prendergast had made his way to the nearest village and arrangements for food and shelter. A little later, as it seemed that the vessel had settled down and showed no immediate signs of any further keeling over, Commander Holland authorized attempts to save the light baggage and anything else possible, and two parties of 60 men were detailed from the King’s Royal Rifles and York and Lancaster Regiment to assist in this task. Harry formed part of human a chain over the rocks from the wreck to the mainland of the island, the baggage was handed down the line for about 100 yards. Work continued until 10 a.m., when Lieutenant St. John, who was in charge at the time, considering the wreck to be unsafe, directed the remaining men to leave the stricken vessel. It was impossible to safe everything but Lt St John knew how the things had been stowed in the hold and was able to save the elephant’s tusk which was the centerpiece of the 1st Battalion’s mess silverware.

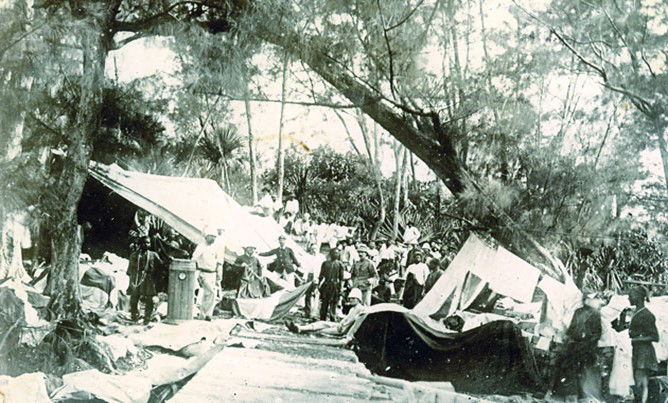

By the morning, the men found themselves on a narrow spit of rocks at the top of which was a grove of palm trees. Captain Prendergast reported back that they were in fact shipwrecked on the southern coast of Reunion not far from the fishing village of St Phillippe. This was a small poverty-stricken village whose population of 1,600 were mainly fishermen or labourers, there was no hotel or inn and the few visitors the village normally received were put up in the priest’s house or at the gendarmerie. The village could not sustain or provide sufficient provisions for the number of men now stranded there.

The troops, with the exception of a small guard placed over the baggage piled on the beach and some sentries close to the ship to prevent any looting, were then collected at Saint Philippe and a roll call was taken. Surprisingly everybody was safe and sound with the exception of two Lascar seamen presumed drowned. The salvaged baggage was brought up to the village, and the exhausted British sentries were relieved by the local French police. Commander Holland managed to telegraph the British Consul, CW Bennett at Saint Denis in the north of the island to advise him of the situation. He also made arrangements for the supply of rations to the troops to be brought from the larger town of Saint Joseph, about 10 miles further along the coast, Fortunately, some preserved beef and biscuits had been saved from the wreck and were available for immediate issue, so the men were able to breakfast and recoup some of the energy they had spent in off-loading the baggage.

Mr. Bennett, the British Consul at St Denis received Forestier’s telegram at 10.30 in the morning , advising that the British transport Warren Hastings had been wrecked near St Phillippe, that all on board were saved and asking whether there was a steamer which could be hired to take the soldiers on board and the crew to Mauritius. There was initially some confusion about the scale of the disaster, for a few minutes later Bennet received from the Governor a copy of a similar telegram which added that the “Warren Hastings” was a little boat of 82 tons belonging to the Mercantile List of Greenock. Without realizing the gravity of the situation Bennet telegraphed the Master of the “Lalpoora” a ship of the British India Company which happened to be in port asking for his aid. It was only after a couple of hours that Bennett learned the true magnitude of the problem down in St Phillippe and that there were some 1,300 shipwreck survivors stranded down there without food, drink or accommodation. Bennett then telegraphed Commander Holland that the Lalpoora would go down to St Phillipe or St Pierre to pick the survivors up. Iin view of the rough seas , it was decided that the men would be sent to the port by the railway from St Pierre.

Bennett , sent his Secretary, Mr. Piat to take the first train down to St Pierre and make contact with Commander Holland and Colonel Walker and offer them every assistance. Piat duly arrived at St Pierre at 8pm in the evening and telegraphed Commander Holland at St Phillippe to ask he could best be of assistance. Holland replied that Piat should wait for him at St Pierre, since he and Colonel Walker were on the way there to prepare for the dispatch of the troops to the port. While waiting, Piat set about trying to find some shelter for the men, he contacted the Mayor of St Pierre and Monsieur Gaillot , Directeur des Marines de Saint Pierre-The latter made available some large warehouses where all the troops could easily be accommodated.

At 2 am in the morning on the 15th Commander Holland and Colonel Forestier reached St Pierre and began preparations for the arrival of the men. The inhabitants of Saint Philippe from the Mayor downwards offered practical help and gave coffee, food, and clothing to individual men. Monsieur Coulon, placed his house and everything he possessed at the disposal of the ladies, and had food available all day for any of them, or the officers who required it, and it was only when practically eaten out of house and home, he was prevailed upon to accept any recompense. Monsieur Alfred Chaton, sous-officier of the Gendarmerie and his gendarmes took on nearly all the guard duty necessary at Saint Philippe. Major Kirkpatrick reported that he had received very material assistance from the Mayors of Saint Joseph, and Saint Pierre who made available a collection of extra carts, without which it would have been impossible to get the bootless men up from Saint Philippe as quickly as was done. The men were now located in huts on a plantation lent by the owner. They also rigged shelters from tarpaulins and other materials salvaged from the wreck. The remaining salvaged rations were collected and distributed. The officers and men shared the same rations , nothing could be bought in St Joseph, as they were not expecting a sudden influx of a thousand shipwrecked British soldiers and therefore had laid in no stock. The authorities now arrived and arrangements were made for provisions.

At 4pm the meal arrived and was issued to the troops. All the huts were packed full and shelter difficult to find. Addyman managed to find an old half covered phaeton to catch forty winks and as darkness and rain set in, he retired for a nights repose.. At midnight on the 14th, supplies of bread arrived and Addyman was called to assist the issue to the troops. The bugler sounded a call and they also sent for men to come and draw bread for their Companies, but mostly the men being were so fatigued and far away, that they did not come for it. Addyman and the 2 QMS sat on the cold steps of the telegraph office waiting for the men to come for them to arrive. By 3.30 am, most of the men had passed by and the last of the bread was issued, Addyman retired to rest, but before saving a few loaves for the officers. At 5-30 am. The troops were roused and ordered to make preparations to move up the coast to the more substantial settlement of St. Joseph.

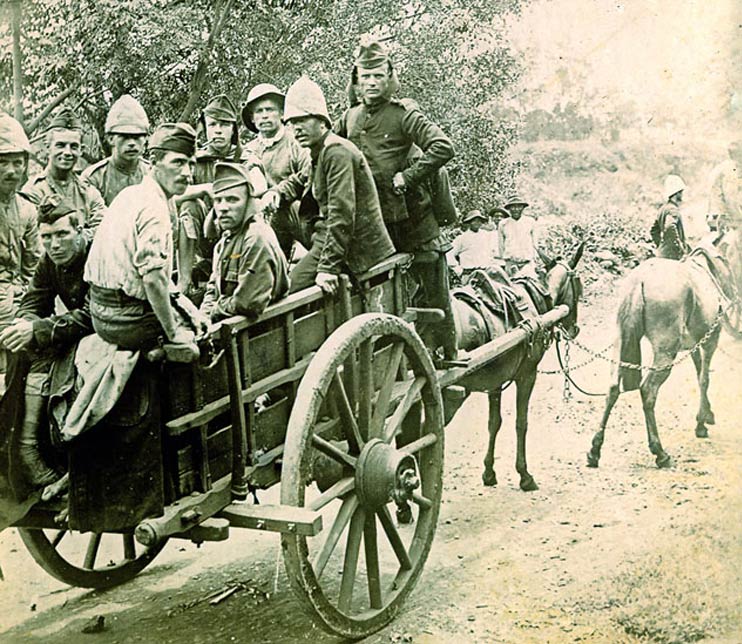

The 1st Battalion KRRC ( 60th Rifles) in temporay shelter on Reunion

At 7 am on the 15th Major Kirkpatrick set off with all the fit men who still had boots , 424 men of the KRRC and 193 of the York and Lancaster Regiment to march the 22 miles along the coast road to St Pierre. They struggled along the road to St Joseph in fairly pitiable state, but they tried to keep a cheerful demeanour while the locals were surprised at they seemed so cheerful and indifferent to their circumstances. Many od the men had no coats, and some even lacked trousers. Stuart Wortley noted one rather stout rifleman clad only in a shirt and a short pair of pants. About 11 o’clock Major Kirkpatrick telegraphed Forestier saying he intended to halt at Saint Joseph for the night They arrived at St Joseph tired out, and drew further rations. Everybody shared alike, officers included and they had dinner in the open, in front of the Church, since it was raining nearly all the time, accommodation was needed and the local authorities here, kindly lent their public school for shelter. The place was already overcrowded so many of the men had to take a few hours rest on the damp ground. Again the local people led by the Mayor of St Joseph and Doctor Courdain provided invaluable assistance and kindness.

At 5.00am on the 16th, the men were all ready to march again toward St Pierre. They had to procure carts for the sick, on the march, after a mile march they had a splendid view of the volcano, which was erupting in the distance with the lava running down like a river. They reached St Pierre and rested until night time to get the train to St. Denis for embarkation. The day was very hot, and the men, with the hard march, arrived there completely done up. Lance-Sergeant was in charge of the rations, and over the boiling stew pans, issuing rations of stew to the men, the officers giving me a hand occasionally, Major Kirkpatrick’s straggling band arrived at St Pierre at 8 am on the 16th .Afterwards they marched to the Railway Station and waited for the train on the road outside the station. The train arrived, and was waved off by cheering locals.

At 2 00 pm they reached the quay side and embark on the BIMS “Lalpoora”, which had been hired to convey them Mauritius. After breakfast some canvas slippers arrived for the bootless, these were purchased, as it was agony for the men without boots tramping over the sharp stone. Addyman observed:

“... We had to procure carts for the sick, and my boots which were nearly falling off my feet. I found that I would be unable to do the march, not having had any rest from I do not know when.The 2nd QMS seeing me done up hired a cart for himself and I, but by the time I reached the end of the journey, my inside was nearly outof me, with the terrible jerks. It was not quite day break, we are now on the march, after a mile march we now have a splendid view of thevolcano, which is a burning one, and at present it is in full play and at its height, the lava is running down like a river. We reach the place(St Pierre) and here rest until night time to get the train to St. Denis, where we embark. This day is very hot indeed, and the men, with the hard march,come in completely done up. I am in charge of the rations, and here I have to serve each man fairly as they come in. I am over the boiling stew pans, issuing to the men, the officers giving me a hand occasionally, with the heat and the steam from the pans I am soaking wet through. I look for all the world as if I was dragged out of a river and just escaped drowning, the work is now over, we march to the Railway Station and now wait for the train on the road outside the station, we look a queer lot all sitting and lying in the road, there are a lot of people waiting to see us off. The train now arrives, and we are all seated, as w are leaving the people cheer us for about a mile down the line, which we heartily reciprocate, until we are quite unable to speak.”

With everybody safe arrangements were set in motion to get the men off Reunion. The Steamship “Lalpoora” was at Pointe des Galets in the north of Reunion and had been chartered for this purpose. Saint Pierre, the nearest place with a harbour where there would be any chance of embarking the men, was about 21 miles from Saint Philippe and it was absolutely necessary that everyone should be got there as soon as possible, as the smaller towns and villages would be unable to find the requisite provisions for so large a force. Carriage for the ladies, women and children, and sick, was essential, and, in addition, there were some 350 men without boots, who could not possibly march the distance; Commander Holland had, therefore, asked the aid of the local authorities at Saint Pierre and Saint Joseph to secure as many carriages and carts as could be got, and, having arranged that the men capable of walking should march the following day, the 15th instant, to Saint Joseph, and that the ladies, women, children, and sick, and as many men as the carts procurable could carry should also start the following morning and go right through to Saint Pierre, he left for the latter place at 8 p.m., with a view to making all further arrangements necessary. The people of the village had been most kind in providing the best accommodation at their disposal, the sick being put up in the Mairie and the women and children in the convent. The men were quartered in two empty enclosures, the best sleeping accommodation which was available being given them, and they were made as comfortable as could be expected under the circumstances.

Commander Holland and Colonel Forestier reached Saint Pierre about 2.15 a.m. on the 15th January. It had been his intention to have the B.I. SS. “Lalpoora” brought round to St Pierre, but she could not have entered the harbour, and the sea was too high to admit of any boats passing in or out, so she was ordered to remain at Pointe des Galets. Fortunately, in the 1870s the French authorities had constructed a railway which ran along the Northern coast of Reunion from St Pierre to St Denis, via Point des Galets. So arrangements were made for a special train to convey everyone from St. Pierre to Pointe des Galets to embark. The old barracks at St. Pierre were placed at the disposal of the British and afforded sufficient and excellent accommodation, especially as it was not intended that anyone should stop there more than a few hours. The women, children, and sick arrived at St Pierre during the course of the 15th in carts and carriages, and at 8 p.m. the train set off for Point des Galets, in which Commander Holland left, together with nearly all the crew of the R.I.M.S. “Warren Hastings,” and as many of the men without boots as had arrived up to then, together with two Officers, in all about 400.

With the assistance of the Mayor of Saint Pierre more carts had been obtained to bring up the remaining men from Saint Philippe, and instructions were sent by Commander Holland to Lieutenant St. John, who with Captain Prendergast, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, had remained in charge, telling him to to arrange to arrive at Saint Pierre by 3 p.m., on the 16th . Commander Holland, went up to inspect the “Lalpoora” at Pointe des Galets, and returned to Saint Pierre by the forenoon train. Forestier left with about 400 men on a special train at 12.50 p.m. and embarked with them on the“Lalpoora,” where they found the women and children, and the men who had gone on the preceding night, lready settled down. Major Gore-Browne, 1st Bn. King’s Royal Rifles, stayed behind to command the men remaining at Saint Pierre, and his party was joined by those with Lieutenant St. John and Captain Prendergast who had marched up from Saint Philippe. They left by train that night with Commander Holland, and reached Pointe des Galets about 4 a.m. on the 17th, when the all of those from the R.I.M.S. “Warren Hastings”” (with the exception of Lieutenants St. John and Windham, R.I.M., and 10 lascars remaining behind for salvage purposes) were embarked on the “Lalpoora,” which sailed at 3 p.m. in the afternoon,

Two French mail boats were in the port and lots of people congregated to see us the shipwrecked British soldiers leave, so led by Bandmaster Tyler ( who had so recently escaped drowning ) and with the instruments the band managed to save, they play the Marsellais, and the locals cheered and saluted them as they left. They reached Port Louis, Mauritius at 6 a.m., on the18th. Addyman described the scene:

“ 2 o’clock. We reach the quay side and embark on the BIMS “Lalpoora”, a cargo steamer, running between here and India, this steamer has been hired to convey us to Mauritius, here I fall on the ship and go to sleep, being completely exhausted and done up, the next morning I was wanted very early, the 2nd QMS of the York and Lancaster Regiment, and a ship warrant officer of the “Warren Hastings”, wanted me to perform some work, but I strongly refused to do it. I told them that they had been on the ship about a day before me and having had nothing to do they had time to have a good rest, as this was not my case. I was not going to do anything until I did have a rest, so went down below for a few more hours rest an d left them with their own work. After breakfast some canvas slippers arrived for the bootless, these were purchased, as it was agony for the men without boots tramping over the sharp stone. I now part with my dear foot breaking boots and procure a pair of the slippers, and thought I was in Heaven, for the comfort my aching feet felt. Well I then tucked in and fitted men without, until being done up by the sun, the officers sent me away, as having no helmet they said I would get sun stroke, and that I had done quite enough. In the afternoon I borrowed a helmet and then assisted to count out the tobacco which was also got for the men, and then issued it to parties concerned. I retire early for rest, thank the Lord, I never slept so like it in all my life,hard boards and no covering is nothing now. Morning 14th arrives, we are now to sail, the moorings are unfastened, and away we sail out of the harbour. Two French mail boats are here and lots of people congregated to see us go, so with the instruments the band managed to save, we play the Marsellais, and the people cheer and salute us fanatically which we also return, it is now more than I can stand. I have to go below crying like a big spoilt child, but I cannot help it I am choked, please excuse me now to again ease my sorrowfulness, I shall never forget this in all my life, and I cannot help tears coming into my eyes at the very mention or thought of it. We get out of the Harbour and put to sea, and all goes well, we reach Mauritius alright about 6 am, the French mail boat arrived before us, and to reciprocate the feelings they all climb the rigging and cheer us heartily in, we now signal to come into harbour, but instead we are put into quarantine, which causes great indignation on board, as we have no provisions, or sanitary arrangements, two latrines for 1300 ship wrecks, besides the ships crew, if we have to stay on the boat much longer. I dread the awful results, shipwreck I think would not be in it, we should soon have cholera amongst us, as the native sailor lascars (Indians) are a filthy and dirty smelling lot, thanks heavens a board of health assembles, and after inspecting everything and everybody we are permitted to disembark. I go ashore in the Generals lot, which is the advance and along with the 2nd QMS and a small fatigue party, we set off to Line Barracks to take them over. I had plenty to do this day getting rations, blankets, bed boards. Having got the men settled down we commence to work to clothe and arm the men, which is the hardest job of all, as there is nothing on the Island, but we are clothed in a way, the police authorities have given us all the clothing they could, a nice lot we look in garbs of various hues.”

The French mail boat arrived before them, and to reciprocate the feelings the crew all climbed the rigging and cheered the British heartily into Port. However, a final problem then arose the ship was put into quarantine, which caused great indignation on board, as they had no provisions, or sanitary arrangements and only two latrines for the 1300 shipwreck survivors and the ship’s crew. Conditions risked becoming intolerable if they were required to stay on the ship for lomg. In the end a boarf of health assembled, and after inspecting everything and everybody they were permitted to disembark.

Addyman went ashore in advance and along with the 2nd QMS and a small fatigue party, set off to Line Barracks to take them over. Since the Warren Hastings had been intended to take the York and Lancaster on to India, there were now two half battalions where there was space for only one and the rifles were put up in the old barracks at Port Louis. Quartermaster Dwane ably assisted by Sergeant Addyman had plenty to do getting rations, blankets, bed boards etc. Having got the men settled down they then commenced to work to clothe and arm the men, which was the hardest job of all, as there was nothing on the Island, but we are clothed in a way, the police authorities have given us all the clothing they could, a nice lot we look in garbs of various hues. The officers were received by the acting Governor of Mauritius, Mr King- Harman at Reduit his country house. There they held a dinner party with the unkempt and unwashed officers of the Rifles making the best of the circumstances. One officer was loaned a suit of the Governor’s evening clothes , the problem was he was 5 ft 8 and the Governor a strapping 6ft 4in. From the 18 January to 3 July Addyman had his work cut out dealing with the problems arising from the loss of nearly all the battalion’s equipment. He worked, night and day continuously, sometimes falling asleep in the chair, with a pen in his hands. The battalion moved from Port Louis to the Hills (Curepipe Camp), and began to get more settled.

Due to the unscheduled presence of the men of the York and Lancaster Regiment accommodation was scarce, however after a few weeks the York and Lancaster Details were embarked for India so there was more room, and the number of patients in Hospital decreased, and the battalion took over the building they had had to misappropriate, and conditions became more comfortable. For at least a few months the Riflemen were not clad in their traditional green with black belts buttons, but a mixture of khali with buff belts, old police uniforms and anything that came to hand. Apart from the elephant’s tusks there were no things for the officer’s & sergeants’ messes, no furniture, no regimental documents or forms to complete. Thanks to the perseverance of Captain Dwane and the local Ordnance department, clothing and arms gradually arrived from England and life slowly settled back to normal after the adventure of shipwreck and rescue.

Commander Edward Holland DSO was subsequently charged with ‘negligently and by default losing a vessel of the Indian Marine Service and was found guilty and reprimanded on 5th April 1897, Lieutenants Walker and Windham were acquitted of all charges. However, none of the Rifles blamed the Captain for the loss of the ship and instead praised him for his coolness and presence of mind and for his care and ability in making arrangements after the wreck. Stuart Wortley attributed the wreck to three principal causes:

- The erupting volcano spewing out minute particles of metal might have effected the compasses

- Similarly the volcano might have caused currents to change

- The bad weather of previous days may have led to anomalous longtitude readings

Notwithstanding his conviction, Commander Holland was made a life member of the KRRC mess. After a bit of a struggle and some questions in Parliament, Officers and men were compensated by the War Office for their loses of private property. 908 rank and file received £1 10 shillings each and officers £30. New uniforms and kit were issued at no charge. Responsibility for the loss of the ship was held to rest with its owner, the Government of India, and compensation for the loss of 2,000 blankets and 1,000 hammocks was sought. The War Office and the India Office wrangled over the costs for most of the year until a letter from the Director of Transports, Admiralty to the Under Secretary of State India Office stated that ‘ in the case of Hired Transports the sea risk of the ship is borne by the ship-owner but sea risk of the Government Stores by the Charterer ( War Office) i.e. by the Government except where negligent navigation is proved ,.

All in all the wreck of the Warren Hastings was a fairly closely run thing. The soldiers and crew were lucky that the ship had struck land in that particular point a small inlet, much further to either side and it would have risked sinking quickly in deep water. Also the Captain’s presence of mind in running the engines forward rather than reversing into the deeper water saved the accident from becoming a disaster on a par with the Birkenhead.

Aftermath

Notwithstanding his court martial, Holland continued his distinguished military career. He received an exemplary order from the Governor of India for his fine conduct and saving of life. Later he served on the Naval Transport Staff, Durban, and as Divisional Officer, 1900-1, being thrice mentioned in Despatches and receiving the CIE. For three years he was principal Port Officer at Rangoon and retired from the RIM in 1905. He then held the post of Marine Superintendent (L & N W Railway and L & Y Railway), Fleetwood. From 1907 onwards he held the post of Marine Superintendent, L & N W Rly, Holyhead. In December 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the European War, became Lieutenant Colonel, RE, and Assistant Director of Inland Water Transport in France. It was largely owing to his efforts that this corps was created. He became Director in 1916, and Brigadier General in 1917 For his services he was three times mentioned in Despatches; received the CB and CMG; was decorated by the King of the Belgians with the Order of Leopold of Belgium, and also by the King of Italy with the Order of St Maurice and St Lazarus.

Colonel Forestier Walker left the 60th Rifles to take a staff appointment , unfortunately he was killed in a train accident in Egypt a few years later. Captain Mark Pechell was an early casualty of the Anglo- Boer War killed at Talana on 20th October 1899 while serving with the 3rd Battalion KRRC. Captain Stuart Worley was wounded and Lieutenant Bernard Majendrie was taken prisoner by the Boers in the same battle. Charles Gosling rose to become a Brigadier General. He was killed in action at Arras in April 1917. Captain Richard Montagu Stuart Wortley went on to have a distinguished military career with the KRRC.

The men of the 1st Battalion went on to serve with distinction in the South African War , particularly at the actions surrounding the siege of Ladysmith.

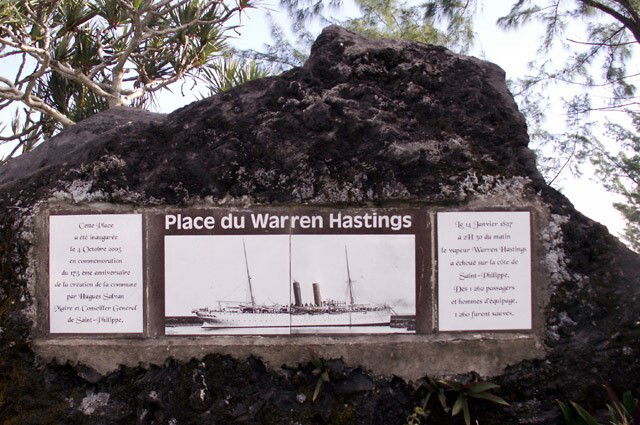

The Warren Hastings itself was sold for scrap for 15,000 Francs to a resident of Reunion but she quickly broke up and the individual was unable to realize much in the way of value from the wreck. A commemorative clock and small memorial tablet were subsequently presented to the villagers of St Phillippe for their assistance with the survivors.