The Prince of Wales on the Italian Front -1917-1918

The Prince

There have been a huge number of accounts written of the Prince of Wales, Wallis Simpson and the Abdication Crisis. Not so much has been written about the Prince’s service during the First World War. In ‘King Edward VIII, The Official Biography’ Phillip Ziegler covers the war in two chapters. In his own memoir “A King’s Story”, the Duke of Windsor (as he was by then known) covers the whole First World War in one chapter of twenty pages titled “The Grim School of War”. Although he spent roughly a year of his four years of war service with the British Army in Italy, the Italian Campaign gets a mere two paragraphs of mention in his memoir. We do come across mentions of the Prince of Wales in Italy in other sources, the most useful of which are the almost daily letters he wrote from March 1918 through to November 1918, to his mistress, Mrs Freda Dudley Ward.. These were published as ‘Letters to a Prince’ edited by Rupert Godfrey. The memoirs, written at a distance of 30 years have the benefit of hindsight and the experience of all that had happened in the intervening period, whereas the letters are the unguarded and controversial views of a not particularly well educated and naïve young man. In the contemporary letters, he comes across as an entirely spoilt, whinging and self-indulgent . Particularly striking is his constant and insensitive lambasting of Britain’s Italian Allies, whom after all the British Government and General Staff had chosen to help in order to relieve the pressure on the Western Front.

Figure 1 Capt. H.R.H. Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, Prince of Wales and Duke of Cornwall, K.G., G. Gds

The Prince celebrated his 20th Birthday on 23 June 1914 just a few weeks before the outbreak of war. On 6th August 1914, he was commissioned in Grenadier Guards, being posted to the 1st Battalion at Warley Barracks in Brentwood, Essex. According to his memoirs, he was extremely pleased to be detailed to the “King’s Company” this despite the fact that at 5ft 7 inches, he was way below the minimum height requirement of 6ft. He describes himself as being “a pygmy among giants”. The Prince joined the 1st Battalion for training, with day long marches and field exercises, which were designed to toughen up reservists who had been recalled to the Colours on mobilisation in August 1914. He does not seem to have received any particularly special treatment, being subject to squad drill by a Sergeant-Major in the same way as all the other Ensigns. After 10 days, the 1st Battalion was moved from Warley to the rather more salubrious quarters of Wellington Barracks, near to Buckingham Place. While the 1st Battalion prepared itself to be transferred to France, the Prince was quietly transferred to the 3rd Battalion which was destined to stay in London. Apparently, this was on the specific orders of Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War[i]. Prince Edward asked Kitchener for a meeting to clarify the situation. As he recounts it, Kitchener was not particularly concerned about him being killed (after all he had three younger brothers), instead he was paranoid about the Prince being captured alive by the Germans (and presumably being used as hostage to bargain with the British). According to the Prince:

“Lord Kitchener’s steely blue eyes met mine. He answered: ‘If I were sure you would be killed , I do not know if I should be right to restrain you, But I cannot take the chance, which always exists until we have a settled line, of the enemy taking you prisoner’ ”[ii]

Kitchener refused to budge, there was absolutely no chance of the heir to the throne being sent to the frontline; however, he does seem to have tried to pacify the Prince by holding up the carrot of a staff job in France sometime in the future. So, when the 1st Battalion sailed for France, the Prince remained with the 3rd Battalion on ceremonial duties in London.

France

In November 1914, Kitchener kept his word and allowed the Prince to go to France as an Aide-de Camp to the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, Field Marshal Sir John French[iii]. French had set up the GHQ of the BEF at St. Omer in the Pas-de-Calais about 30 miles behind the frontline and out of earshot of all but the heaviest artillery barrages. Throughout his time at St Omer, the Prince asked his father to be allowed to go on more active service nearer to the front. One of the Prince’s first roles in St Omer was to turn out for the funeral of the legendary figure Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts VC, 1st Earl Roberts. The 82 year old Roberts, known to most of the British Army and the wider public by the sobriquet “Bobs” had been on a nostalgic visit to Indian Divisions in France ( he had started his military career in India) . While at St Omer he had caught pneumonia and died. Given the rather dire military situation, there were few British troops available to give the Field Marshal the appropriate military send off, so it fell to the GHQ Staff and some available Gordon Highlanders to do so. The Prince of Wales watched while the legendary figure who served in most of Queen Victoria’s “small wars” from the Indian mutiny through to the Boer War was taken by gun carriage through St Omer, while the Gordon Highlanders played the “Flowers of the Forest” and a very big war raged 30 miles away. The Field Marshal wad then taken, somewhat unceremoniously, by ambulance back to the UK for burial.

This seems to have been the high spot of the Prince’s time in St Omer. According to his account, he describes Field Marshal, Sir John French as surrounding himself with older officers and friends, who still thought of tactics in terms of the Boer War. “They liked their food and their comforts and in the opinion of the men in the trenches were quite out of touch with what was happening in the front line.” While burdened with paperwork and the day to day administration of the BEF, the Prince continued to lobby his father for a posting to Bethune which was then only five miles from the front line. In the end he got his way but did not stay long, the British were preparing an offensive at nearby Neuve Chapelle, and Sir John French evidently lost his nerve about the Prince being so near the front and had him transferred back to the rear.

At the beginning the Prince was under the charge of a middle-aged Colonel Barry, who was responsible for his day to day will being. In January 1915, Barry was joined by Lord Claud Hamilton referred to in the Prince’s letters as Lord Claud. Lord Claud was the youngest son of James Hamilton, 2nd Duke of Abercorn and a Captain in the Grenadier Guards in 1909. He was the Machine-Gun Officer of the 1st Battalion, and in October 1914 his team of gunners worked for 7 days and nights without relief whilst under fire from enemy artillery and machine-guns. They fired 57,000 rounds of ammunition and inflicted 'considerable loss' to the enemy. For this Lord Claud he was mentioned in despatches in 1914 for having "commanded a machine-gun for five days and nights without relief" and made a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order. By November the battalion was so decimated that they were formed into just one company, Lord Claud was one of the few remaining officers left alive, so it was probably fortunate for that he was ordered to act as the Prince’s personal Aide de Camp , and away from the front-line. The Prince already knew Lord Claud from his time at Warley barracks, so it was a good choice.

Although, the Price seems to have rather uncomplimentary regarding Sir John French, French gives him some low key praise in a despatch dated 5 April 1915, writing :

“His Royal Highness continues to make most satisfactory progress. During the Battle of Neuve Chapelle he acted on my General Staff as a Liaison Officer. Reports from the General Officers commanding Corps & Divisions to which he has been attached agree in commending his thoroughness in which he performs any work entrusted to him. I have myself been favourably impressed by the quickness with which His Royal Highness has acquired knowledge of the various branches of the service, and the derp interest he has always displayed in the comfort and welfare of the men. His visits to the troops, both in the field and in hospitals, have been greatly appreciated by all ranks. His Royal Highness did duty for a time in trenches with the battalion to which he belongs.”

In spring 1915, the Prince finally managed to get free of Sir John French and was a attached to the staff of 1st Army Corps under Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Monro based at a chateau in the environs of Bethune. It gave the Prince the opportunity to visit friends in the front line trenches.

In September 1915, he joined the staff of the newly constituted Guards Division as ADC to Major General Lord Cavan. Cavan had served with Grenadier Guards during the Second Boer War, retiring from the British Army on 8th November 1913 as a Colonel. Recalled to service at the start of World War 1, Cavan was appointed commanding officer of the 4th (Guards) Brigade on 11 August and led the Brigade at the first Battle of Ypres in October 1914 and the Battle of Festubert in May 1915. Apart from a couple of breaks, the Prince ended up serving with Cavan for most of the rest of the war.. The Prince describes Cavan as follows;

“Frederick Rudolph Lambart, Earl of Cavan – ‘Fatty’ to his brother officers and friends – was of my father’s generation , a Grenadier and a keen sportsman who was deeply proud of having fulfilled the two ambitions of his life; to command the 1st Battalion of his regiment and to be Master of the Herefordshire Hounds.”[iv]

The Prince liked serving in the Guards Division, where he knew most of the officers from “childhood dancing classes, from Oxford, from country-house shooting parties, from hunting and from the West End. The Guards Division was a great club; and, if tinged with snobbishness of tradition, discipline, perfection , and sacrifice. The Prince served with the Guards Division through the winter of 1915/16 , on 11 December, 1915 he wrote to his father from the HQ at La Gorgue.

“My dearest Papa,

……..Except for the wet all goes on the same as ever, both in the trenches & in the rear; its dull and monotonous life for us all, but far worse for the regimental officers !! Poor old people they do have a most miserable time. You know well enough the type of man who officers the Brigade of Guards; well his life may be summed up as follows for 18 days

2 days in a ditch 2 days in a dirty French cottage

2 days “ “ “ 2 days “ “ “ “ “

2 days “ “ “ 2 days “ “ “ “ “

6 days in a dirty French dwelling in a filthy little town!!

What a life indeed & what must be the effect on their brains? It’s a terrible thing, this alone & I almost wonder why some of them don’t go mad!! Yet they always seem wonderfully cheery and seldom grouse…. “[v]

In early 1916, he ordered to visit Imperial Forces in the Middle East. In his memoirs the Prince says that he was “glad of an opportunity to see a new theatre of operations and I also welcomed the chance to get to know the magnificent Australian and New Zealand troops- the ANZACS- who had recently been evacuated from Gallipoli”[vi] . On his first day at GHQ, the Prince went to see General Birdwood[vii] address the ANZACs and he received a rising reception from the men, Birdwood maintained that that the men took him to their hearts.

At the time of his visit, the Suez area was particularly quiet, so the Prince was able to make some diversions elsewhere. He made a trip to the Sudan, where the Governor Reginald Wingate[viii] laid out the red carpet for him. Whilst in Khartoum the Prince rode over the battlefield at Omdurman, with “officers who still talked of General ‘Chinese’ Gordon[ix] and some who had fought the dervishes on this very field.” Apparently, the Prince did not relish the cultural side of Egypt, especially trips to the pyramids and the Temple of Karnak. In his diary he wrote; “I am utterly fed up with visiting temples and never want to see another one again.” He was somewhat more taken with the more dubious fleshpots of Cairo and longed for another visit there. At the end of his visit, the Prince submitted a report on the Transport and Supply Arrangements in the Canal Zone. This was a rather short summary of the existing position in 1200 words. However, Lord Kitchener thought it did the Prince great credit. Kitchener , like Sir John French in his despatches, presumably had to be careful at giving his princely feedback at just the right level, While the practical output from the Prince’s Middle Eastern trip might have been negligible, he certainly made a worthwhile impression on the Australian and New Zealand troops. It was here in Britain’s semi-colony of Egypt mixing with the Dominion and Colonial troops that Edward’s devotion to the concept of the British Empire was renewed.

It was while returning from his trip to the Middle East, that Prince Edward paid his first visit to Italy. He went to visit King Vittorio Emmanuele III at his wartime HQ, the “Villa Italia” near Udine. During the visit the Prince had gone with the King to inspect Italian defences along the Isonzo River, in Friuli Venezia Giulia. At 5ft exactly in height, the 47 –year old Italian King was even shorter than the Prince. Both the King, who was reputedly bilingual (the Savoys were connected with France) and the Prince could speak French, so at least they could converse about the state of the war, although also present was the head with of the British Military mission, Lt. Col. Sir Charles Delmé-Radcliffe. Delmé-Radcliffe had been military attaché to Rome from 1902-1911, where he became friends with King Vittorio Emmanuele III and many of the leading Italian politicians and soldiers of the day. He had been a natural candidate to lead the British military mission. Presumably Radcliffe obliged with the translations if necessary. Other than the war, there probably was not a lot to talk about, apart from his family the King’s abiding passion was numismatics which was unlikely to have been of great interest to the Prince.

Back from his trip, in May 1916, Prince Edward was promoted to Captain and awarded the Military Cross, much to his discomfort[x] To his credit, he did not actually believe that he deserved either of them and that both resulted from his father’s string pulling which they probably did. On his return to France he re-joined the HQ staff of Lord Cavan’s, who was by then promoted and commanding the XIV Army Corps. The Prince spent the winter of 1916- 17 on the Somme. by then the Prince was observing;

“By then the war had become an indescribable mass carnage, and the slaughter was terrible. As things turned out, I was to spend nine months in these unattractive surroundings, living in a camp of canvas huts through the coldest bleakest winter of the war. Most of our energies were absorbed in the struggle to provide as much comfort for the troops as the primitive and rugged conditions would allow.”[xi]

In 1917, Piers ( Joey) Legh was appointed as a further companion to the Prince, He too was a well-connected officer in the Grenadier Guards , whose father the 2nd Baron Newton ( Thomas Legh) was the Paymaster General in Herbert Asquith’s Government and from 1916, the controller of the Prisoner of War Department.

In May 1917, XIV Corps moved back to the Ypres sector, where it was to participate in the Battle of Passchendaele. The Prince had another lucky escape, when a shell hit the rooftop observation point at Langermarck church -fortunately he had dived our of the way to escape two previous near misses. After the offensive fizzled out into nothing other than sheer loss of life and exhaustion, Prince Edward became more weary, cynical and disillusioned with the whole war. Back at HQ He wrote to his father;

“But how thankful I am to think I am not living forward tonight & am sitting back here in comfort; one does appreciate this comfort when one has been forward & seen what it’s like in the line now !!The nearest thing possible to hell whatever that is !!”[xii]

Figure 2 Lord Cavan, in relaxed mode.

Italy

Meanwhile on the Italian Front, the Austrians had launched a major offensive, which had resulted in the rout of the Italian Army at Caporetto. The Italians were now in full retreat as the Austrians occupied most of Friuli Venezia Giulia. On 24 October, the Italian Government appealed for British and French help. The British and French resolved to send an Expeditionary Force to Italy to support the Italians who were falling back to a defensive line at the River Piave. Instructed to select a Corps Commander two infantry divisions to send to Italy, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig [xiii]chose Cavan as Corps Commander, with the 23rd and 41st Divisions placed under his overall command. Cavan pleaded that the Prince accompany them, mainly for public relations purposes.

While the British divisions awaited order to entrain in France, Cavan and his staff (including the Prince) set out for Italy. They arrived at Pavia ahead of the main body of the XIV Corps on 5 November 1917, from where they drove to Padua, here they met up with Delmé-Radcliffe whose British Military mission had been forced to retreat to safer area after Caporetto [xiv] .Cavan’s party also visited King Vittorio Emmanuele III and conferred with various Italian generals. The Italian GHQ and British Military Mission been forced to relocate to Padua many miles behind the new Italian defence line at the Piave. Next day Cavan’s party drove to Treviso to meet General Cadorna at his HQ in the Palazzo Revedin near to the Italian front line. While at Treviso, Cavan also met with his French Counterpart, General Denis Auguste Duchêne whom the Prince described as “an able man tho’ a notoriously rude one”. Meanwhile, the Italians fired General Cadorna as Supreme Commander replacing him with General Armando Diaz[xv], Cadorna was given the role as Italian representative on the Allied Supreme War Council. Cavan and his staff moved to Mantua, where it had been agreed that British troops arriving from France would be concentrated, on 11 November the British 23rd Division began detraining in Mantua, On 13 November, General Sir Henry Plumer arrived in Mantua to take over what had now become the 4th British Army in Italy, Cavan reverted to commanding the XIV Corps. British units then began their long march from Mantua to what had been designated as the British sector, the area around Montello on the River Piave.

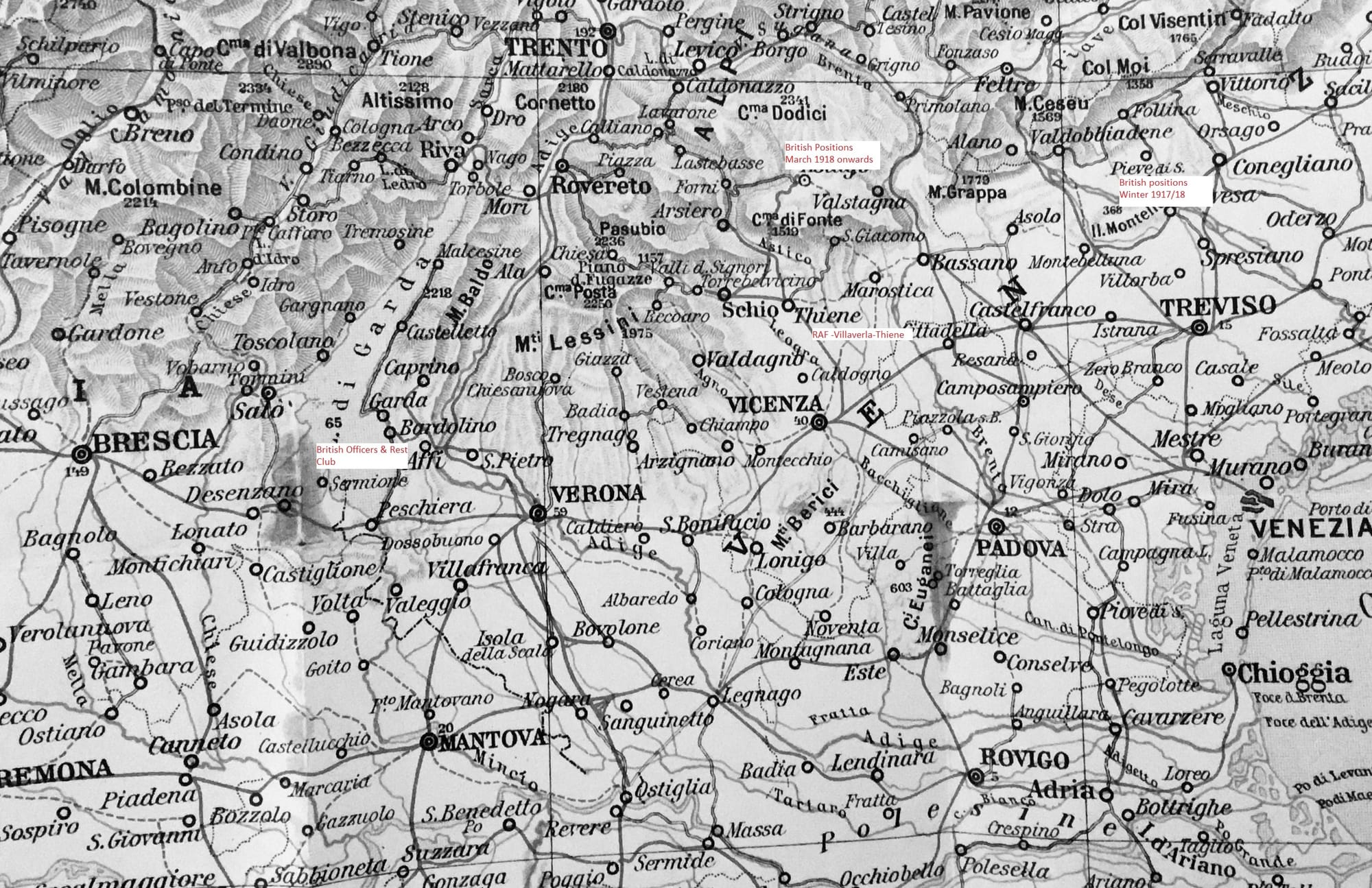

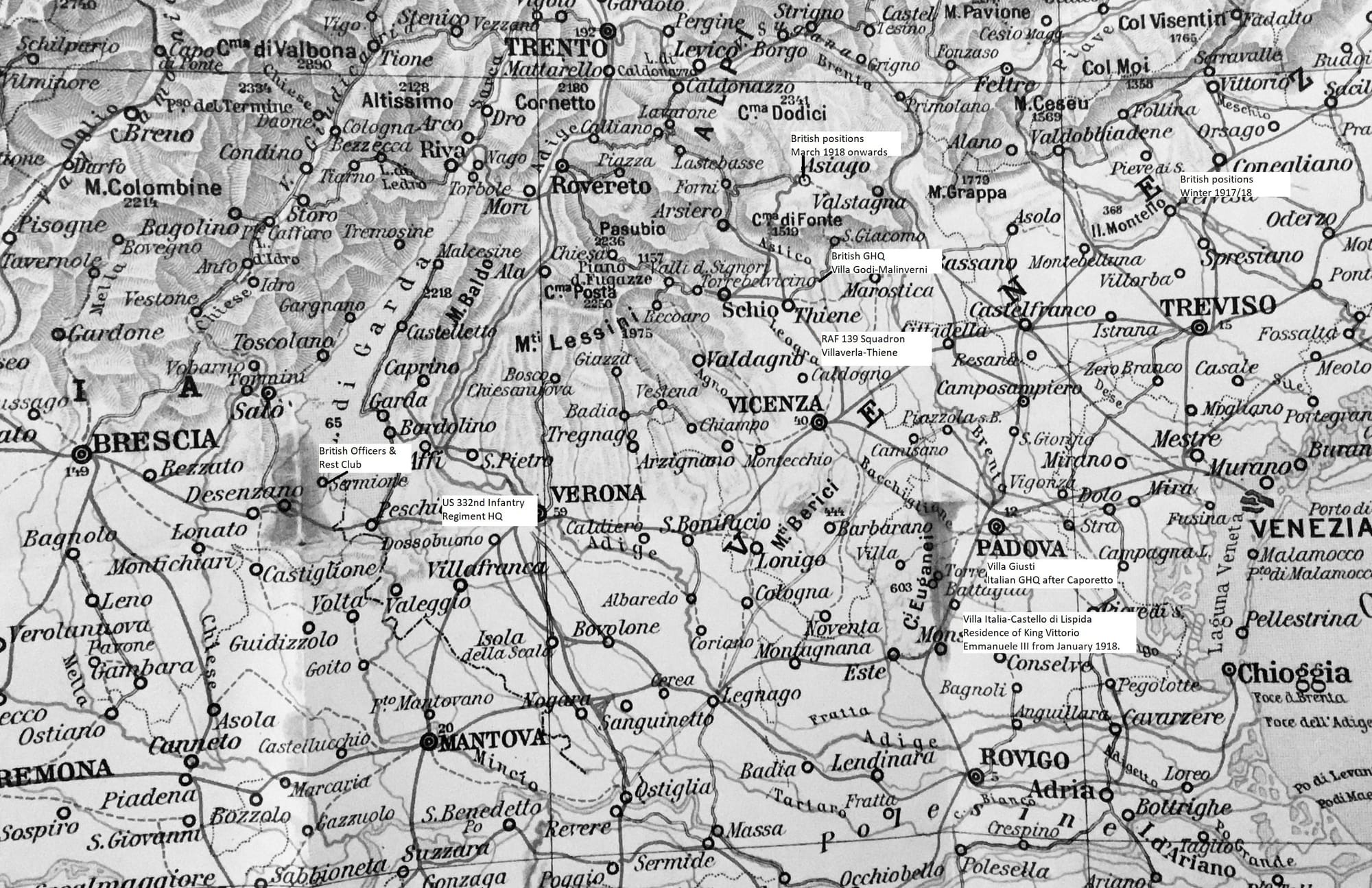

Map showing locations mentioned in this article

XIV Corps established its HQ at the Villa Emo, a Palladian villa at Fanzolo about 20 miles outside Treviso and a similar distance from the front at Montello. Just as British Headquarters Units in France, were habitually based in Chateaux, the Headquarters in Italy tended to base themselves in a selection of splendid Palladian Villas (Villa Emo, Villa Godi) . Fortunately Palladio had built most of his villas in the Veneto , so there was a good choice available.

Figure 3 The Villa Emo in Fanzolo. The HQ of the British XIV Corps for the Montello Sector

In his memoirs, the Duke of Windsor dismisses the whole Italian campaign in a couple of paragraphs, neatly summarised as. “For a whole year we froze in winter and sweltered in summer at our Headquarters on the Venetian Plains, without any signs of significant advances or retreats”. From a purely military perspective that is a quite accurate summary, but there were a few other points of interest on the way.

On 19 December, the Prince visited front line positions at Montello, visiting the Northumberland Fusiliers. In his book “Across the Piave”, Norman Gladden describes the visit:

“We had heard that he had already been in our vicinity during the march from Mantua, but it was not easy to identify personalities among the brasshats who had appeared from time to time as we moved across the country- not that the Prince was difficult to distinguish. Now he certainly did arrive outside the billet, showing particular interest in our new brick-built cookhouse and other changes wrought during our short stay. Possibly this had been one of the main intentions. From afar he appeared to be keenly interested , but almost overwhelmed by the crowd of bigwigs who hovered about his slight form, seeming from a distance to be steered by the sheer weight of their presence.”[xvi]

One British officer told a " I had the Prince of Wales in the back of my cab Story " Major EH Hody of the RASC was driving back fron 23rd Division HQ at Montebelluna towards the camp at San Floriano when two staff officers hailed him for a lift , one was tall the other "a slighter build fair amd good-looking and noticeable for two rows oof coloured ribbons on his breast - an unusual display for one so young. The officers asked if he coud give them a lift to Corps HQ at Fanzola. Hody recognised the Prince and seizeed the opportunity to sit next to him in the back of the car, engaging him in conversation. He was greatly impressed by the Prince who had a " charm and fredom of manner that made one feel instinctively at ease. " From their brief encounter, Hody concluded that the Prince was well-informed about the situation in Italy and that from his questions he knew what he was talking about. "

The Prince had only been in Italy a couple of months, when he was called back returned to the UK in January 1918 to tour defence factories. His tour included visits to shipyards and aircraft factories on Clydeside where he tried his hand at riveting, a descent into a Welsh Coalmine at Ebbw Vale and visits to the munition factories at Woolwich Arsenal. By March 1918, von Ludendorff’s Spring Offensive was ripping through the British lines and looked as though the British might be pushed back to the sea. The Prince recalls that ;

“ One evening at Buckingham Palace my father suddenly looked up from his war maps and said: “Good God! Are you still here? Why aren’t you back with your Corps? When I explained the reason, he told me I must be off by morning, adding that he could not have me seen around London, with the British line broken and the Army with its back to the wall. I left immediately”[xvii]

Rather than sending the Prince to France it was judged prudent to send him back to the altogether quieter and safer confines of the Italian Front. While in the UK, the Prince struck up a relationship with Mrs Freda Dudley Ward[xviii]. On his return to Italy, he pursued an almost daily correspondence with Freda, which at least gives a flavour of his service in Italy.

Figure 4 Mrs Freda Dudley Ward

Making his way back to Italy via Boulogne and his favoured Paris stopping off point, the Hotel Meurice, the Prince arrived back at Cavan’s HQ in Vicenza on 1 April 1918. While, the Prince had been away from the Italian front, the British Divisions had been relieved from the front at Montello and sent instead to face the Austrians on the Asiago Plateau. XIV Corps HQ had moved from Villa Emo to Villa Godi another Palladian Villa in the foothills below Asiago at Lugo Vicenza, which was near enough to allow a day trips to the front by car to the front returning safely by the evening.

Figure 5.Villa Godi, XIV HQ after the XIV Corps moved to the Asiago Mountains

Figure 5.Villa Godi, XIV HQ after the XIV Corps moved to the Asiago Mountains

Almost as soon as he unpacked, the Prince was writing to Freda. He sent his letters, using the King’s Messengers, who was more properly engaged in delivering correspondence between the British HQ in Vicenza and the War Office in London. For the Prince of Wales, it seems to have been a handy private postal service. On 4th April 1918, he wrote;

“ Our GHQ is not such a bad spot considering, being a comfortable “villa” in the foothills of the Asiago mountains; we have 4 divisions out here , 2 of which are in the line up in the mountains, from opposite Asiago to a few kilometres to the West, an interesting luckily quiet sector !. I was up there yesterday and visited two OPs and got wonderful views which is a pleasant change from sitting in muddy trenches in Flanders. “[xix]

The Prince soon starts moaning about the problems of getting leave from Italy (he had only been back there a few days for goodness sake) and the boredom he was suffering. In his next few letters, he continues to moan about the boredom and monotony of life at GHQ, although at least having the good grace to concede that he is sitting in comfort in northern Italy and not in the middle of Northern France. In April, he is sent off to liaise with the Italian Supreme Commander, General Diaz, who he reports as being a bit of a bore. On 8th April he complains about getting up at 6.00 am the next day to visit British positions in the mountains. “I hate having to shove off before 9.00, I hate getting up before 8.00 am at the earliest “. The statement seems rather lacking in empathy for the average British soldier in France who was waking up before 6.00 am for another dawn attack and who was most probably dead by the time the heir to the throne was having breakfast. It is quite interesting to contrast the Prince’s views on Sir John French and the staff officers living the soft life behind the lines in France (written in his memoirs some 30 years later) with his contemporary writings to Mrs Dudley Ward, where he appears guilty of much the same thing.

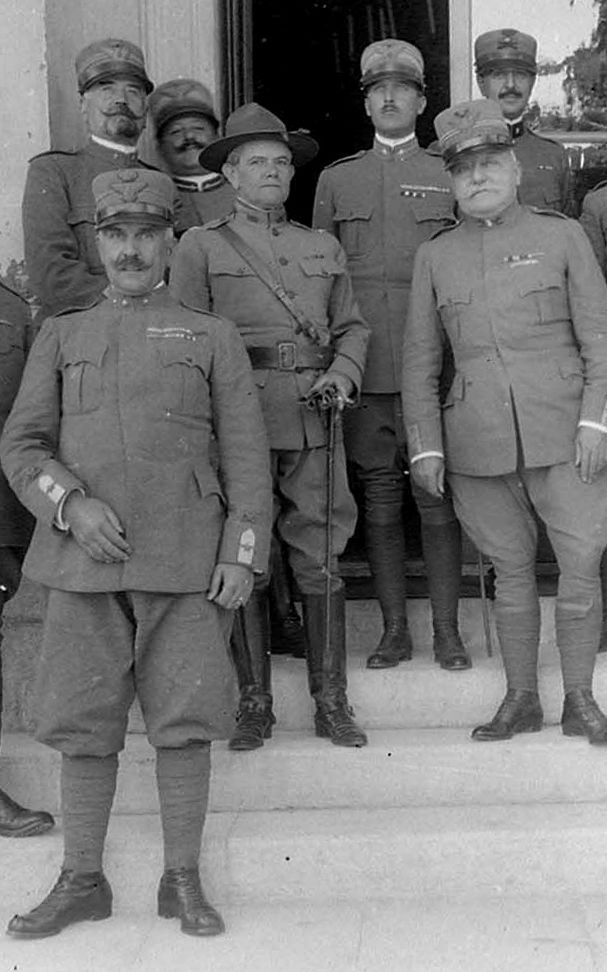

Figure 6 Lord Cavan with the Italian General Diaz and French General Graziani.

The Prince’s days seem to have consisted of motoring from GHQ to various British positions on the Asiago Plateau and then returning to Vicenza to eat and sleep. The Italians had kindly lent a 35 hp Lancia staff car for the purpose. There was a good road up to the Asiago plateau running up from Lugo di Vicenza, up through Caltrano and Tresche di Conca (now the SP349) but it was full of hairpin bends. In winter it became covered with ice, snow and slippery mud, making conditions even more treacherous. Vehicles needed to be driven with the greatest care, since there were nothing but a sheer drop down the slopes of the mountain. British made cars, suffered from steering problems on the roads and from radiator problems in the summer and the Italian vehicles were found to be much more reliable. The Prince was fortunate to have the Lancia at his disposal for his frequent tries up into the mountains. On 11th April, he writes;

“I went up into the mountains early on Tuesday and had a long walk in “no man’s land” in front of our front line trenches though behind our outpost line which I a long way out!! But we have a very quiet and cushy sector and I wasn’t so very frightened though of course I was a bit!”[xx]

Figure 7 A 1914 35 hp Lancia Theta

Letters on the 18 and 19 April show the Prince in unsympathetic form, blaming the King’s Messenger for delivering one of Mrs Dudley Ward’s letters late. The poor messenger, travelling down through war torn France for the main purpose of delivering important military correspondence had missed a train connection in Turin. By 19 April, the Prince is moaning about being on duty in “the beastly office”. I would imagine that several hundreds of Imperial officers and men who died on 19 April 1918 on the various fronts of the war rather wishing they were in a “beastly office” instead.

Characteristic of Edward’s correspondence is a general disdain for most of Britain’s allies apart from the French. He routinely refers to the Italians (who he is supposed to be supporting) as “ice-creams” or “dagoes”. This seems in marked contrast with many of the other memoirs written about the Italian Army, by other members of the British Italian Expeditionary Force, which are usually highly complementary. He is also for some reason particularly unkind about the 60,000 man Portuguese Expeditionary force, which for some reason the Portuguese Government had despatched to the Western Front. For sure, the Portuguese Army might not have been the most effective force, and by early 1918 was being dogged by mutinies left, right and centre. Nevertheless, it took a severe mauling from the German Army at the Battle of Lys in April 1918, which effectively destroyed it as an effective fighting force. Perhaps fortunately, the Portuguese did not have access to Edward’s letters to Freda when they gave him safe haven in July 1940, following the Fall of France.

Between visits to the front, Prince Edward was to be found visiting members of the Italian Royal Family, including a royal relative the Duchess of Aosta who was living near Vicenza[xxi]. As Princess Helene of Orleans, the Duchess had wanted to marry the Prince’s Uncle, the Duke of Clarence; however she was a Roman Catholic and permission was refused. The Duke even considered giving up his right of succession to marry her, but in the end the whole thing fell through. With the benefit of hindsight maybe the Prince could have picked up a few points from the Duchess on the problems of Royal marriages.

Obtaining leave from the Italian Front back to the UK was difficult, life in Italy was not without its benefits. May of 1918 found Edward in Venice for a trip, in the next few days he was off to inspect a French Gunnery School on Lake Garda, so not a wholly bad life. By 13 May he was back to his normal moaning ways, basically complaining to Freda, that his less than onerous military duties are interfering with his correspondence with her!

“I am being interrupted the whole time by that----------- telephone. We are rather short-handed in this---- office now”[xxii]

Apart from the bad spelling and poor grammar, another hallmark of the Prince’s correspondence was the expletive deleted! Never mind the ringing telephone was probably some unfortunate British unit, requesting some fire support up on the plateau.

At the end of May 1918, the Prince went to Rome to participate in the Italian celebrations of the Third Anniversary of their declaration of war. Quite why the Italians were ‘celebrating’ the start of war that had seen several hundred thousand of their compatriots killed, a huge military defeat and the loss of a substantial part of the Northeast of their country, is a good question. However, he went down to Rome anyway. Arriving by train from the north of Italy he was was greeted as a State visitor. In Rome stayed at the British Embassy as a guest of the British Ambassador, Sir James Rennell Rodd. Rodd was hugely experienced on the Italian scene, having been the Ambassador to Rome since 1908, and indeed instrumental to persuading the Italians to join the Allies. A career diplomat, he had entered the British Diplomatic Service in 1883, and served at embassies in Berlin, Rome, Athens and Paris. In typical Foreign Office fashion he had. then been sent to Sweden for a few years before returning to Italy. Rodd describes the official ceremony as follows

“The ceremony in the Augusteum [xxiii], at which we sat in the box of the Regent, the Duke of Genoa, was a very moving one. A glance round the crowded arena revealed how representative a gathering had met there. Senators, deputies, generals, officials and simple men and women of the people, fathers and mothers of soldiers who had given their lives for their country, or were holding the bulwark of the Piave, were commingled in the stalls. One box was filled with officers who had lost their sight in action. In another might be seen the staff of the Czecho-Slovak division, formed chiefly from prisoners of war, which was being trained and equipped in Italy. In the gallery were the red shirts of Garibaldi's veterans.

After the orchestra had played the national anthems of the Allies, and there were now a goodly number of these, the Syndic of Rome, Don Prospero Colonna, addressed warm words of welcome from the city to the Prince of Wales. He reminded those who were present of the vow taken on the Capitol that same day in the year 1915 to maintain concord and sacrifice everything for the country. The Prince then rose, and in a clear voice which carried well, with just a little touch of boyish shyness that went straight to the hearts of his audience, said that he had come to bring a message of encouraging sympathy from the King his father and his subjects in Great Britain and in the Dominions overseas. When he concluded with these words:

‘In the city of Rome, the ancient capital of the world, the source of social order and justice, I proudly proclaim my conviction that the great object for which our two nations are fighting against the forces of reaction is inevitably destined to triumph, thanks to the union of which our meeting to-night is symbolic’”[xxiv]

Prince Edward and Sir James were hosted by the Duca di Genova, the King’s Uncle who was effectively acting as Regent in Rome, while the King led the Italian forces at the front. The Prince describes him as being ‘old & gaga’. The Prince also visited the Queen and younger members of the Italian Royal Family at the Villa Savoia in Rome, where they were living while the Quirinale Place was being used as a hospital for the war wounded. The Prince describes the Queen of Italy as looking like’ a big unattractive housemaid’. On Sunday, he was taken for a picnic with the Queen and her children “out to their chateau & woods on the sea I hour in a car from the town “. At the time the Royal Family had a couple of houses on an estate known as the “tenuta di San Rossore”, set in pine woods and facing the sea just outside Pisa, so this may be the pace to which hr refers. .[xxv]

Figure 8 Villa Savoia in Rome, home of the Italian Royal Family

Figure 9 the Italian Royal Viila at San Rossore

While in Rome, the Prince visited Pope Benedict XV[xxvi] at the Vatican. King George V, apparently objected to the visit, but the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Balfour insisted it was an essential diplomatic visit. The Pope had been engaged in various peace moves, in August 1917 he had presented a ‘peace note’ to the warring parties. The note proposed a peace linked to justice rather than military conquest, a demand for a cessation of hostilities, a reduction of armaments, a guaranteed freedom of the seas, international arbitration, and Belgium restored to independence and guaranteed "against any power whatsoever." All sides should forgo claims of compensation (which were to prove so disastrous a part of the Versailles Treaty later), since most of the damage, in like Belgium and France, had been caused by Germany, the Allies saw this idea as effectively favouring their principle enemy. Only Britain was willing to explore the possibilities of the note. Perhaps Balfour was more interested in gaining support from the Papacy for the idea of a British mandate in Palestine and support for the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Speaking through his mouthpiece, The Daily Express Lord Beaverbrook condemned the visit as the: “Visit which should not have been made”. The Express blamed the King for not having vetoed it. Since Beaverbrook was in the government at the time, this did not really go down well with George V. Clearly, the Prince as being sent into a diplomatic minefield; however, he did not seem that bothered one way or another. He described the visit as follows;

“Monday morning I had an audience with the POPE at the Vatican, an interesting experience in its way, though he is an unprepossessing little man, a dirty little priest with spectacles who hadn’t shaved for several days, though he did talk French!! The whole place was stiff- with cardinals & I was glad to get out of it!!!!”[xxvii]

Figure 10 Pope Benedict “an unprepossessing little man”

As with his previous tour of the Middle East, the Prince does not seem to have had much interest in the historical cultural sights of Rome. The extremely cultivated Rodd, seems to have done his best to show Prince Edward, the key sites in Rome, but his efforts seem to have been unappreciated, since Prince Edward comments:

“We went to St. Peter’s & the ruins of ancient ROME and saw the real Colleisium( sic) though I’m afraid I was terribly bored & have flatly refused to do anymore sightseeing as its too ‘ereintant? (exhausting) in top of all these official stunts”[xxviii]

The Prince’s attitude seems to have been in stark contrast to the hundreds of British officers and men, who took the opportunity to take their leave in Italy, soaking up the rich history and culture of its cities. Instead, the Prince seems to have preferred to stop by the Excelsior Hotel in via Veneto to partake of cocktails in the company of Lord Claud, which they apparently did twice a day. In the end the Prince left Rome, without any of his insulting comments about the Italian Royal Family becoming common knowledge, so his visit can actually be considered a success for Allied relationships.

As mentioned, previously life in Italy was not without its small pleasures. The British had taken over two hotels at Sirmione del Garda (previously used by German tourists) as a rest centre for officers and men. Following his return from Rome, the Prince was at Sirmione with Lord Claud and Joey Legh for a visit to the rest camps, in his letter to Mrs Dudley Ward, he reports that possibly because of taking a dip in the lake, he has now gone down with influenza and is running a temperature of 101F . Unlikely that the Lake was the cause, since at that time influenza or mountain flu was ripping through the British forces on the Asiago plateau. It seems likely that this was actually the Spanish Influenza, whose first and less lethal wave was spreading through Europe throughout April and May 1918.

In 15 June 1918, the Prince was at GHQ when the Austrians launched their Solstice Offensive all along the Italian front. In a last of the dice, they attacked across the Asiago Plateau and along the River Piave to the sea. On the Asiago plateau, they had some initial success breaking through the British lines at San Sisto Ridge before being repulsed in the late afternoon. During that particular engagement, Captain Edward Brittain MC of the 11th Battalion Sherwood Foresters , the author Vera Brittain’s brother was killed. On the Piave, the Austro_ Hungarians had more success, crossing the river and getting up onto the Montello before being halted by a dogged Italian defence in the middle of the hill. On 17 June, the Prince wrote to Mrs Dudley Ward;

“I meant to write by Saturday’s KM but the Austrians had the cheek to attack us early that morning, though we were expecting it. 48 hours before there was a fearful wind- on Friday and I never got a moment to write. ……The attack was a general one from here to the sea & I’m afraid the ice creams haven’t done as we and the French have, repulsed the attacks. They have lost a good deal of ground in places, particularly on the PIAVE and we are very fed up with them, though I think we have good reason to be don’t you? They are the most hopeless people & not really worth fighting for, though their men are all right, it’s their -----------generals & staffs.”[xxix]

Next day the Prince went to the British frontline at Asiago, visiting the points where the Austrians had broken through the British lines and been repulsed. He stopped and talked to the British units and reported:

“I saw a few corpses but not as many as most of them have been buried by now; but ail our men are in the best of spirits& have their tails right up. All say they had a good shoot on Saturday, though they got properly shelled in the morning. ……“But this battle does make us proud of ourselves and pleased with the French, though more sick than ever of & with these old dagoes!!!”[xxx]

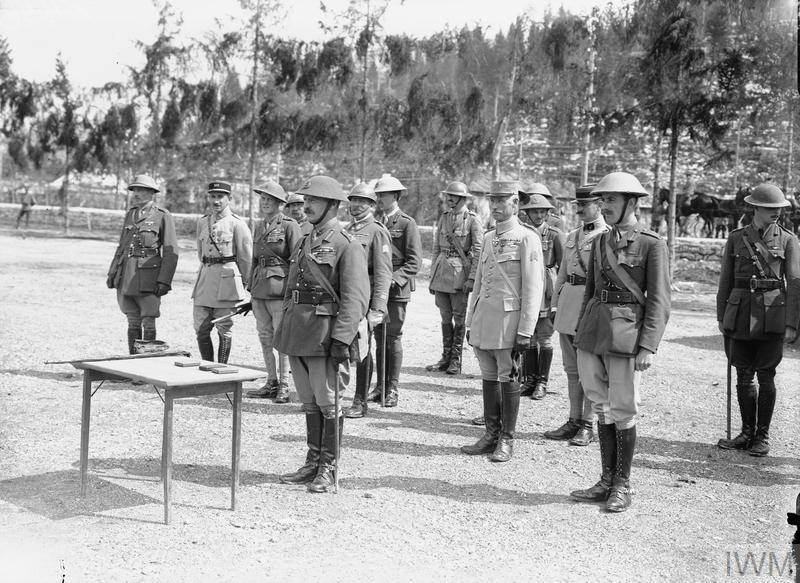

The King and Queen’ Silver wedding was to take place in in June and Edward discussed with the Earl of Cavan, whether to return home for it, given the events of the past few days and the possibility that the Austrians would regroup for another attack, they decided it was not the right time to leave the front. On 12 July, he accompanied Cavan up to the British field HQ at Granezza to take part in medal ceremonies.

Figure 11 Lord Cavan, The Prince of Wales, the French commander General Graziani and assorted officers handing out medals at Granezza , July 1918

Figure 11 Lord Cavan, The Prince of Wales, the French commander General Graziani and assorted officers handing out medals at Granezza , July 1918

Meanwhile, the Italians rallied and managed to evict the Austrians from the Montello and back across the Piave and things settled back to all quiet on the Italian Front. After the battle, Prince Edward again visited Venice to look at the Italian defences along the mouth of the Piave and found time to again visit the rest station at Sirmione, for a swim and a short relax. On 25 July, he was back to his official duties at Istrana near Treviso, presenting the military medal to four Italian soldiers who had rescued a British pilot downed in the River Piave. . Writing about the event on the same day, he also mentions his horror on learning of the murder of his relative the Czar of Russia and his family. He describes the Czar as being “a charming man, but hopelessly weak.”

On 7 August, the Prince returned to Venice. In his letter for that day he complains about having to return early to Villa Godi to meet the Maharaja of Pattiala for dinner. Bhupinder Singh was educated at Aitchison Chief's College in Lahore and was a talented polo and cricket player. In 1911, he captained the India XI that toured England. He was also extremely loyal to the British empire. Patiala State sent more than 28,000 men to fight in the war and their involvement encouraged other Sikhs in the Punjab to volunteer; nearly 89,000 in total They also contributed a lot of cash was The Maharaja had attended an Imperial War Cabinet in London in June and being attached the General Staff, was making a tour of Imperial Units in Europe- he held the honourary rank of Major- General in the British Army. [xxxi] The Prince was keener on golf, than cricket, so maybe the conversation turned to polo which the Prince occasionally played with British Cavalry units in the area. After the war, the Maharaja would play host to the Prince, when he toured India in 1922. It turned out that they did have something in common, in the 1930s both the Prince and the Maharaja met with Adolf Hitler and got on rather well, Hitler gave the Maharaja, a Maybach limousine as a present.[xxxii] While undoubtedly being diplomatic to his face the future Emperor of India was rather dismissive and disrespectful to the Anglophile Maharaja in his next letter to Mrs. Dudley Ward.

“Thank goodness Pattiala & suite left this afternoon; it’s such a bore having to entertain these sorts of parties & worse still trying to find sleeping accommodations for them!! And Indians aren’t very attractive guests to say the least of it. Very dark men with beards!!”[xxxiii]

Figure 12 The Maharaja of Patiala on Tour of Indian forces in France

The Royal Public Relations role continued, On 9 August 1918, he was over at the Italian HQ i to have dinner with the King of Italy. Apparently, he did not appreciate either the quality of the dinner or the two-hour drive back to the Villa Godi. After Capporeto , the Austro/Hungarians had overrun the former Italian HQ near Udine and since February 1918, the King had used a new Villa Italia, the Castello di Lipsida near Monselice. South of Padua. The Italian Commando Supremo was nearby at Villa Giusti in the suburbs of Padua. Considering the wartime conditions and the 35hp Lancia at his disposal, 2 hours seems like quite an optimistic time for the drive back to Vicenza. On the 8 and 9 August, the British and French had been in action on the Asiago Plateau. The Prince notes :

“We had some successful little operations last night, several raids which brought in about 400 prisoners of war & put the wind up the Austrians & the French are doing the same tonight & evidently hotting them up properly too, as they are making a lot of noise now as I write & I can see the gun flashes from my window”[xxxiv]

In early August 1918, intelligence reports suggested that the Austrians were planning to withdraw their frontline to higher ground, the other side of Asiago to the lower slopes of Monte Interotto and Mont Catz, where they had been constructing a Winterstellung (Winter Line) . This would have left the Austro-Hungarians in a much stronger defensive position, since like the allies they would have had the advantage of the pine forests behind them providing cover from observation and allowing them to resupply in daylight. Although it meant abandoning Asiago, the town had now been so thoroughly destroyed that apart from its propaganda value it was of no significant benefit for them. Furthermore, as the snow fell the Austrian would have been in a horribly exposed position down on the Plateau, with any movement in and around the town leaving highly visible tracks to allied observers. Further intelligence from a deserter suggested that the Austrians might withdraw be as early as 10th August. Rather than let the Austrians retire quietly to the North – the Allies determined to attack. At a staff meeting on 5th August General Luca Montouri of the Italian 6th Army , in the company of French General Graziani and the Italian General Pietro Badoglio suggested to General Cavan a British-.French attack to anticipate the Austrian withdrawal. It seems Cavan agreed reluctantly to an attack, but realising the British could not held on to any ground taken, he agreed instead to two large-scale raids. The British attacked on 8/9th August and the French on 9/10th August. One of the few casualties of the raids was Captain William Edward DSO, MC of the RAMC. Lister was killed instantaneously by the concussion of a Trench mortar bomb, which fell near him. He was 31 years old.

On 11 August 1918, Prince Edward took a two-hour drive in the Lancia from Villa Godi to Sommacompagna, to the west of Verona on the road from Peschiera del Garda. Here he had lunch with Colonel Wallace commanding the newly arrived American 332nd Infantry Regiment who had established their headquarters there. In February 1918, the Americans had agreed to send a token presence to Italy to show their support, consisting of an American Field Hospital[xxxv], American aviators and the 332nd Infantry Regiment. On their way from France towards the front, the Americans paraded through Turin, Milan, and various other Italian cities getting rapturous welcomes everywhere they went. The King of Italy had already visited the 332nd Regiment, so they were getting used to royal visitors. At that time the Regimental HQ was in the charmingly named Villa Mille e Una Rosi, ( the Villa of a 1001 roses) Wallace was from Indianapolis, a former engineer and West Point graduate, he had been in the US Army since 1891 and had seen service in the 1898, Spanish- American War in both Cuba and the Philippines. It is interesting to speculate on how the lunch conversation between the veteran 54-year-old Hoosier and the naïve 23 year- old heir to the British throne might have gone. Strangely, the Prince does not say anything rude about the Americans, in later years he developed a great affection for all things American, including obviously American women.

Figure 13 US Colonel William Wallace with various Italian generals in Milan, July 1918

The quiet period up on the Asiago Plateau gave the Prince the opportunity to try something that was later to become one of his passions, flying aeroplanes. He drove the Lancia to nearby Villaverla to meet up with an RAF Squadron. Cavan was on leave at the time, so maybe the Prince seized the opportunity to do something that the would otherwise have been unable to do. On 16 September, he writes:

“I’ve had a marvellous ‘fly’ this evening in a Bristol fighter with a wonderful Canadian pilot called Baker, who has downed about 40 Huns & Austrians. I went to tea with his squad& he took me up afterwards & it was too thrilling for words darling & we went up to 10,000 ft and over the mountains and got a marvellous view of the lines & saw miles into Switzerland and Austria”[xxxvi]

The Prince gets the pilot’s name wrong it was Barker. The number of Austrian and German planes downed is substantially correct, as is the type of aeroplane. When the 4th British Army had been sent to Italy in 1917, it was accompanied by two squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps, 28th Squadron with Sopwith Camel fighters and 34th Squadron with two seat RE 8 aircraft (used for observation and air support). These were subsequently joined by 42nd Squadron (RE8’s) and the 45th and 66th Squadrons (Sopwith Camels). Among the pilots who went south to Italy with 28th Squadron, was Canadian William George Barker

[xxxvii]. Flying out of Grossa, on 29 November, Barker had shot down an Austrian Albatross D.III fighter to be followed shortly after by another Austrian plane and a balloon. Barker had joined 66 Squadron where he racked up another 16 kills by July 1917. Following the formation of the Royal Air Force, Barker finally became squadron commander of the newly formed 139 Squadron in Italy. Although Barker continued to prefer his single seater Sopwith Camel, 139 Squadron also had a flight of two seat Bristol F2B fighters, which is the type that the Prince refers to. It was while serving with this squadron at Villaverla- Thiene near Vicenza, that Barker took the Prince of Wales for flights over the Italian Front.

Figure 14 A Bristol F2B aeroplane, of the type in which William Barker took the Prince for a spin.

By October 1918, Austrian resistance in Italy was collapsing. Just under a year after he had first arrived in Italy, the Prince returned to France to visit Imperial forces and was with the Canadian Corps in France at the time, the Armistice was signed.

All told, the Prince spent nearly a year of his four years at war on the Italian Front. Perhaps, it is unfair to criticise him too much, his letters and diaries suggest that he deeply wanted to be in action at the front. Left to his own devices, he might well have fought and died there. However, Lord Kitchener and especially Field Marshal Sir John French seem to made strenuous efforts to keep him as far from the front as possible. By all accounts, he seems to have performed the tasks he was given well enough, he probably was not given enough of them. Maybe, in the end just being there may have been enough. The Prince’s letters from Italy especially exhibit boredom with his pointless staff jobs. To be fair to him, he did his job; he wrote reports, pinned on medals, visited newly built cooking facilities, visited the sick and wounded and glad-handed various senior British, French, Italian and American officers, and the odd Maharaja. There really was not much else for him to do. For the British having the heir to the throne in the Italian Theatre of War, was something of a public relations victory, it is just fortunate that none of Prince Edward’s unguarded comments about Britain’s Italian Allies found their way into the public domain. Perhaps the Price himself provides a suitable conclusion in his memoirs;

“While my military duties were circumscribed and my role certainly an usual one, yet my education was widened in war, not through book or theory, but through the experience of living under all kinds of conditions with all manner of men.[xxxviii] “

[i] In 1914, at the start of the First World War, Kitchener became Secretary of State for War. One of the few to foresee a long war, lasting for at least three years, and with the authority to act effectively on that perception, he organised the largest volunteer army that Britain had seen, and oversaw a significant expansion of materials production to fight on the Western Front. On 5 June 1916, Kitchener was making his way to Russia on HMS Hampshire to attend negotiations with Tsar Nicholas II when the ship struck a German mine 1.5 miles west of Orkney, Scotland, and sank. Kitchener was among 737 who died.

[ii] HRH Duke of Windsor, ‘A King’s Story’ , Cassell and Company Ltd, London 1951 page 109

[iii] Sir John French was Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) for the first year and a half of the First World War. He had an immediate personality clash with the French General Charles Lanrezac. After the British suffered heavy casualties at the battles of Mons and Le Cateau, French wanted to withdraw the BEF from the Allied line to refit and only agreed to take part in the First Battle of the Marne after a private meeting with Lord Kitchener, against whom he bore a grudge thereafter. In May 1915 he leaked information about shell shortages to the press in the hope of engineering Kitchener's removal. By summer 1915 French's command was being increasingly criticised in London by Kitchener and other members of the government, and by Haig, Robertson and other senior generals in France. After the Battle of Loos, at which French's slow release of XI Corps from reserve was blamed for the failure to achieve a decisive breakthrough on the first day, H. H. Asquith, the British Prime Minister, demanded his resignation

[iv] HRH Duke of Windsor, ‘A King’s Story’ , Cassell and Company Ltd, London 1951, page 120

[v] HRH Duke of Windsor, ‘A King’s Story’ , Cassell and Company Ltd, London 1951 page120

[vi] HRH Duke of Windsor, ‘A King’s Story’ , Cassell and Company Ltd, London 1951 page121

[vii] General William Riddell Birdwood, was Commander of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps during the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915, leading the landings on the peninsula and then the evacuation later in the year. In February 1916 the Australian and New Zealand contingents, back in Egypt, underwent reorganisation to incorporate the new units and reinforcements that had accumulated during 1915: the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was replaced by two corps, I ANZAC Corps and II ANZAC Corps, and Birdwood reverted to the command of II ANZAC Corps.[viii] Sir Reginald Wingate had spent most of his career in the Sudan , And yes hed had been at the battle of Omdurman

[ix] Major-General Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, In early 1884 Gordon had been sent to Khartoum with instructions to secure the evacuation of loyal soldiers and civilians and to depart with them. In defiance of those instructions, after evacuating about 2,500 civilians he retained a smaller group of soldiers and non-military men. Besieged by the Mahdi's forces, Gordon organised a citywide defence lasting almost a year that gained him the admiration of the British public, but not of the government, which had wished him not to become entrenched. Only when public pressure to act had become irresistible did the government, with reluctance, send a relief force. It arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed.

[x] Supplementary Gazette of 3 June 1916 ( page 5570) lists the Military Cross as awarded to Capt. H.R.H. Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, Prince of Wales and Duke of Cornwall, K.G., G. Gds. The award was part of the Birthday honours List

[xi] HRH Duke of Windsor, ‘A King’s Story’ , Cassell and Company Ltd, London 1951 page122[xii] HRH Duke of Windsor, ‘A King’s Story’ , Cassell and Company Ltd, London 1951 page122

[xiii] Haig commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until the end of the war. He was commander during the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Arras, the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), the German Spring Offensive, and the final Hundred Days Offensive.

[xiv] Delmé-Radcliffe was born in 1864 into the British landed aristocracy. Educated at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, he was commissioned in 1884 and saw little active service; but was an excellent linguist, while in Italy he was a witness to the Vesuvius eruption of 1906 and the relief operations for the Messina earthquake in 1908..

[xv] General Diaz, born in 1861 came from a family of Spanish origin. He was an Artilleryman and Staff college graduate, who had commanded an infantry regiment in thec1912 Libyan Campaign, he had served Cadorna as Secretary and then became Head of the Operations

[xvi] Norman Gladden, “Across the Piave”, HMSO London 1971.

[xvii] HRH Duke of Windsor, ‘A King’s Story’ , Cassell and Company Ltd, London 1951- page 123

[xviii] Born Winifred May Birkin, Freda was the second child and eldest of three daughters of British Colonel Charles Wilfred Birkin (fourth son of a lace embroidery and tableware magnate of Nottingham,), and his American wife, Claire Lloyd Birkin (née Howe). Her first marriage was on 9 July 1913 to William Dudley Ward, Liberal MP for Southampton. They had two daughters. Her first husband's family surname was Ward, but 'Dudley Ward' became their official surname through common usage. Their divorce took place on the ground of adultery in 1931. The relationship between the Prince of Wales and the married Ward was common knowledge in aristocratic circles.

[xix] Letters from a Prince , Edited by Rupert Godfrey , Warner Books , London 1999 page 15

[xx] Letters from a Prince, page 20

[xxi] Princess Helene D’Orleans – later SAR Principessa Elena D’Aosta , was the Inspector General of the Italian Red Cross. Technically, she was not related to the British Royal Family, she was a member of the exiled French Royal Family the Bourbon-Orleans who had been living in London and nearly married into the British Royal Family. She had wanted to marry Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale , the eldest son of the future Edward VII, so Prince Edwards’s uncle. During the spring and summer of 1890. Marriage to a Roman Catholic would have entailed constitutional forfeiture of Eddy's claim to the British throne, pursuant to the Act of Settlement, but Hélène offered to become an Anglican. Clarence offered to renounce his succession rights if necessary, writing to his brother: "You have no idea how I love this sweet girl now, and I feel I could never be happy without her". His mother agreed with the match, as did his father. The prime minister, Lord Salisbury expressed objections to the alliance to the Queen in writing at length on 9 September. Hélène's father refused to countenance the marriage, was adamant she could not convert and informed the Queen of his decision. He granted permission, nonetheless, for Hélène to personally beseech Pope Leo XIII for a dispensation to marry Clarence, but the pope confirmed her father's verdict and the courtship ended. Clarence never got over his feelings for Hélène and their relationship is commemorated at his tomb at Windsor Castle by a bead wreath with the single word "HELENE" written upon it. On 25 June 1895, at the Church of St. Raphael in Kingston upon Thames, Hélène married Prince Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy, 2nd Duke of Aosta (1869–1931).He was at the time second in line to the Italian throne. The wedding was attended by Crown Prince Victor Emmanuel of Italy, the Prince and Princess of Wales and others of the British royal family.

[xxii] Letters from a Prince, page 36

[xxiii] The Augusteum (The Mausoleum of Augustus ) is a large tomb built by the Roman Emperor Augustus in 28 BC on the Campus Martius in Rome, Italy. The mausoleum is located on the Piazza Augusto Imperatore, near the corner with Via di Ripetta as it runs along the Tiber. After the fall of Rome, parts if it wre built over asnd used as a castle, then a garden, and finally as a circus. In the early 20th century, the interior of the Mausoleum was used as a concert hall called the Augusteo, until Mussolini ordered it closed in the 1930s and restored it to the status of an archaeological site, It has now been restored and should shortly reopen to the public.[xxiv] https://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/Social_and_Diplomatic_Memories._Third_Series._1902-1919

[xxv] Pisa definitely seems more than an hour by car from Rome, closer to three or four- so it my not in fact be the place, but from the description of the Pineta and he sea, seemed to be quite a strong candidate, also in the absence of any other likely candidates. The Villa at San Rossore was a favoured Royal residence where they usually spent the period from June to November. As a sad footnote to history, it was here that King Vittorio Emmanele III signed Italy’s Legge Razziale in in 1938, introducing widespread discrimination against Italy’s Jewish population and the expulsion of foreign-born Jews from Italy. The Savoy’s favourite summer residences were blown up by the retreating Germans in 1943 and the site now houses the summer palace of the President of the Republic of Italy.

[xxvi] Elected by the College of Cardinals in 1914, Benedict XV described the First World War as "the suicide of civilized Europe". He immediately declared the neutrality of the Holy See and attempted from that perspective to mediate peace in 1916 and 1917. Both sides rejected his initiatives. German Protestants rejected any "Papal Peace" as insulting. The French politician Georges Clemenceau regarded the Vatican initiative as being anti-French. The Italians believed that many cardinals were in favour of the Catholic Austro-Hungarians and went as far as demanding that German and Austro-Hungarian diplomatic representatives be expelled from the Vatican . With no support for his peace initiatives Benedict XV focused on humanitarian efforts to lessen the impacts of the war, such as attending prisoners of war, the exchange of wounded soldiers and food deliveries to needy populations in Europe. After the war, he repaired the difficult relations with France, which re-established relations with the Vatican in 1921. His last concern was the emerging persecution of the Catholic Church in Soviet Russia and the famine there after the evolution.[xxvii] Letters from a Prince, page 43

[xxviii] Letters from a Prince, page 41[xxix]Letters from a Prince, page 50

[xxx] Letters from a Prince, page 51

[xxxi] The Maharaja had as many names and titles as Prince Edward , at that time he was more fully known as ; Major-General His Highness Farzand-i-Khas-i-Daulat-i-Inglishia, Mansur-i-Zaman, Amir ul-Umara, Maharajadhiraja Raj Rajeshwar, 108 Sri Maharaja-i-Rajgan, Maharaja Sir Bhupinder Singh, Mahendra Bahadur, Yadu Vansha Vatans Bhatti Kul Bushan, Maharaja of Patiala, GCIE, GBE,

[xxxii] After the war , the Maharaja represented India at the League of Nations in 1925, and was chancellor of the Indian Chamber of Princes for 10 years between 1926 and 1938, also being a representative at the Round Table Conference. He also became famous for his rather flaboyant lifestyle In 1927 The Times reported ‘the flamboyant Maharaja arrived at Boucheron (in Paris) accompanied by a retinue of forty servants all wearing pink turbans, his twenty favourite dancing girls and, most important of all, six caskets filled with 7571 diamonds (and) 1432 emeralds, sapphires, rubies and pearls of incomparable beauty’.In 1928 surpassed himself at Cartier when he provided the Parisian jewel house with 2930 diamonds, rare Burmese rubies and the 234-carat De Beers diamond (the seventh largest in the world) and commissioned a platinum chain festoon necklace set with this king’s ransom of gemstones. When the Maharaja of Patiala was in town, tradesmen and hoteliers struck gold. In London he stayed at The Ritz and commissioned Bond Street fancy goods firm Asprey to make monogrammed travelling trunks for his five wives. When staying at the Hotel Bristol in Vienna in 1928, the Maharaja insisted on taking the cook and waiters with him on a privately chartered train to Budapest. He was reputed to have a fleet of 20 Rolls Royce cars. The Maharaja also had in the region of 350 concubines , it was said that he would position naked favourites from his harem around his iced swimming pool so he could steal a caress or a sip of whiskey while he swam.

[xxxiii] “Very dark men with beards!!” appears to be an in-joke between the Prince and Freda Dudley Ward. He uses the same phrase tp refer to the Italian as well. [xxxiv] Letters from a Prince, page 85

[xxxv] There is an obituary notice for Colonel Wallace ad an interesting set of profiles of the men of the 332nd Regiment at the following link.

https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/profiles-of-us-service-in-wwi-italy/332nd-inf-soldier-profiles.html?start=9

Also interesting on the subject are

“ In Italy with the 332nd Infantry”

https://archive.org/details/initalywith332nd00lett/page/n8/mode/2up

“Ohio Doughboys in Italy”

https://archive.org/details/ohiodoughboysini00wall/page/n4/mode/2up

[xxxvi] Letters from a Prince, page 100

[xxxvii] Born on a family farm in Dauphin, Manitoba, "Will" Barker grew up on the frontier of the Great Plains, he fell in love with aviation after watching pioneer aviators flying Curtiss and Wright Flyer aircraft at farm exhibitions between 1910 and 1914. In December 1914, soon after the outbreak of the First World War, Barker enlisted in the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles. The regiment went to England in June 1915 and then to France on 22 September of that year. In March 1916, when he transferred as a probationary observer to 9 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps, flying in Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 aircraft.[8] He was commissioned as a second-lieutenant in April and assigned to 4 Squadron and later transferred to 15 Squadron, still flying in the B.E.2. He was awarded the Military Cross for this action in the concluding stages of the Battle of the Somme.[In January 1917, he commenced pilot training at Netheravon, flying solo after 55 minutes of dual instruction. On 24 February 1917 he returned to serve a second tour on Corps Co-operation machines as a pilot flying B.E.2s and R.E.8s with 15 Squadron. After being awarded a bar to his MC in July, Barker was wounded in the head by anti-aircraft fire in August 1917. After a short spell in the UK as an instructor, he transferred to newly formed 28 Squadron, flying the Sopwith Camel . On 7 November 1917, 28 Squadron was transferred to Italy with Barker temporarily in command, and most of the unit, including aircraft, travelled by train to Milan Barker was transferred back to the UK in September 1918 to command the fighter training school at Hounslow Heath Aerodrome. Barker ended his Italian service with some 33 aircraft claimed destroyed and nine observation balloons downed, individually or with other pilots. Barker returned to Canada in May 1919 as the most decorated Canadian of the war, with the Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Service Order and Bar, the Military Cross and two Bars, two Italian Silver Medals for Military Valour, and the French Croix de guerre. He was also mentioned in despatches three times. He died in 1930 when he lost control of his Fairchild KR-21 biplane trainer during a demonstration flight for the RCAF, at Air Station Rockcliffe, near Ottawa, Ontario. Barker, aged 35, was at the time the President and general manager of Fairchild Aircraft in Montreal.[25]

[xxxviii] HRH, the Duke of Windsor, ‘A King’s Story’ Cassell & Company , London 1951