The end of the war in Italy - 80 years on ( Part 2) Crossing the Po - 21st April to 30th April 1945

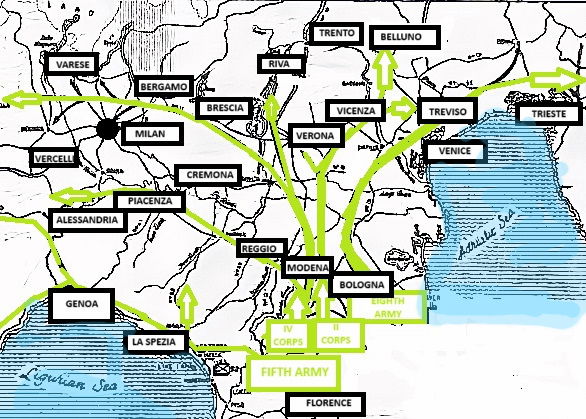

On 21st April, the Fifth Army launched its advance to the Po with II Corps on the right and IV Corps on the left . The plan was for all troops drive to the Po on the Borgoforteto -Sermide line, with Ostiglia as dividing point between corps. General Truscott's emphasised speed. For the first time in the Italian campaign the Germans were falling back in terrain suitable for swift pursuit. They were short of vehicles and fuel and were retreating across an open valley with a superb network of roads for the American mechanized forces. The river stood between the Germans and their retreat.

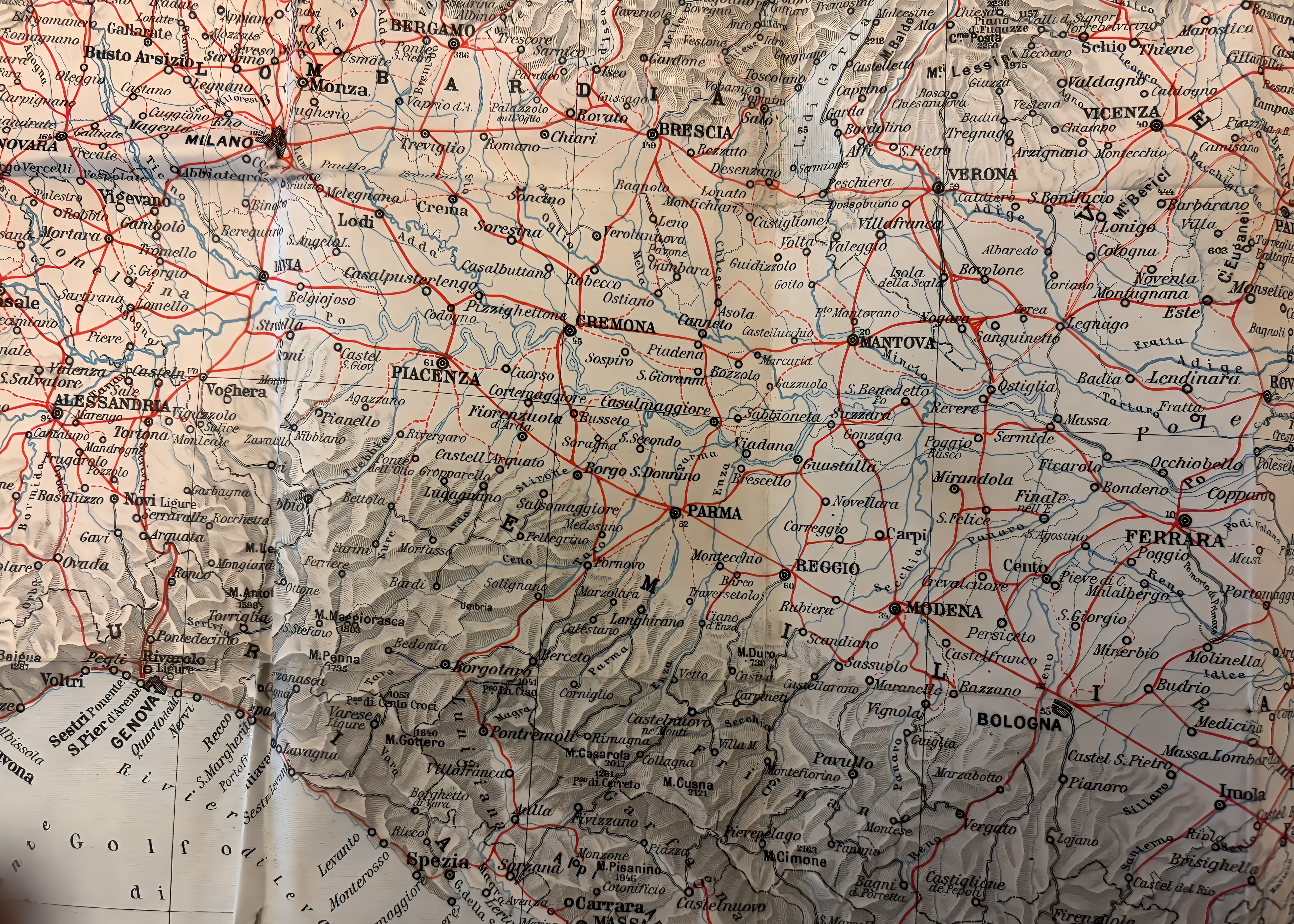

Reading the official history of the multiple river crossings by different units , became rather confusing, so here is an attempt to simplify . First it is necessary to understand the geography. In the satellite photo below, you can see the Po running through the centre of the photo. At the foot of the photo you can see the Apennines,, the mountain chain running up the centre of Italy , until finally, along the line of Bologna to Modena, the mountains finish and the Po Valley starts. The Allies had been fighting their way up the mountainous spine of Italy, in inhospitable terrain and bad weather until by Spring of 1945, they were finally within sight of the Po valley and its easier terrain. In the top of the photo, you can see Lake Garda and beyond that the Alps and the Brenner Pass. The Brenner Pass was the only way out for the large German armies trapped in Italy, so you can see why the Allied plans involved a swift crossing of the Po and a dash towards th Alps to cut of German egress from Italy. In the following account, numerous rivers are mentioned. It was not as easy as heading north from Bologna to the Po. The route involved first crossing the river Panaro , the final right-hand tributary to the Po, which runs right across Emilia-Romagna in a north-easterly direction: from its source close to the Apennine watershed, The Panaro runs through Vignola, Finale Emilia and Bondeno entering the Po at Ficarola to the West of Ferrara. If you see these rivers in summer, they are often dry ,but in Spring following snow melts and rain in the mountains, both the Panaro and the Po, would have been at their widest extent and most difficult to cross.

Next we need a bit of simplification on all the units involved. The Allied forces were divided between the Fifth Army in The Centre and the East and the British Eighth Amy on the East. The Fifth Army was split into two corps , IV Corps to the west of Bologna and II Corps in the Centre . It helps to understand that is going on to understand the Order of battle of each Army. Without going into granular detail , the main units were.

| FIFTH ARMY | EIGHTH ARMY | |

| IV CORPS | II CORPS | |

| 10th Mountain Division: 85th Mountain Infantry Regt, 86th Mountain Infantry Regt 87th Mountain Infantry Regt | 34th Division: 133rd Infantry Regiment 135th Infantry Regiment 168th Infantry Regiment | 56th Division: 169th (London) Infantry Brigade 24th (Guards) Infantry Brigade |

| 1st Brazilian Division | 88th Division: 349th Infantry Regiment 350th Infantry Regiment 351st Infantry Regiment | 2nd Commando Brigade: |

| 1st US Armored Division: | 91st Division: 361st Infantry Regiment 62nd Infantry Regiment 363rd Infantry Regiment | 2nd New Zealand Infantry Division: 8th Indian Division: |

| 92nd Division 365th Infantry Regiment 370th Infantry Regiment 371st Infantry Regiment | 6th South African Armored Division: 11th South African Armored Brigade: |

In the advance to the Po, Allied units pushing forward in the centre ran into comparatively light resistance; on either flank they found the Germans willing and able to put up stiff opposition. On the left flank the German Fourteenth Army had collapsed west of the Reno and the remnants of XIV Panzer Corps fled north of Bologna, LI Gebirgs Armeekorps, still relatively intact and west of the American attack, instituted an orderly withdrawal from its mountain positions north across Highway 9. Consequently, the thrusts northwest along that highway by the 1st Armored Division and then by the 34th Division met a series of well-organized delaying forces in the vicinity of Modena and Parma . On the right flank the German 1 Fallschirmjager and 4 Fallschirmjager (Parachute)Divisions fought fiercely to cover the exposed right flank of Tenth Army as it fell back across the Po before the British Eighth Army. in the centre due north of Bologna, there was a complete gap in the German's line. With the exception of the Panaro River line, where the Germans made a futile effort to hold open the bridges at Bomporto and Camposanto, the resistance encountered was disorganized and ineffective, consisting chiefly of small knots of soldiers dug in around houses or along canal banks. The Panaro River defence line was makeshift and proved no major obstacle; both the Bomporto and Camposanto bridges, ready for demolition though they were, were taken intact by troops of IV Corps on 21-22 April and so speeded up the race to the Po.

IV Corps

In the West, General Crittenberger utilized the 1st Armored Division on the left, the 10th Mountain Division (reinforced) in the centre, and the 85th Division on the right. The Brazilian 1st Division was immediately west of the 1st Armored Division and was to reconnoitre aggressively and follow enemy withdrawals; the 365th and 371st Infantry on the lightly held extreme left were also to continue following the enemy.

The 10th Mountain Division was commanded by Brig. Gen. George P Hays. Ever since Finland’s “Winter War” with the Soviet Union, American planners had been considering the need for a specialist Mountain Warfare unit. The utility of such a unit was confirmed when they received reports that Greek mountain troops had held back superior numbers of unprepared Italian troops in the Albanian mountains during the Greco-Italian War. The Italians had lost 25,000 men in the campaign because of their lack of preparedness to fight in the mountains. On 22 October 1941, General Marshall decided to form the first battalion of mountain warfare troops for a new mountain division. On 8 December 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent, the army activated its first mountain unit, the 87th Mountain Infantry Battalion (which was later expanded to the 87th Infantry Regiment) at Fort Lewis, Washington. It was the first mountain warfare unit in U.S. military history. The National Ski Patrol took on the unique role of recruiting for the 87th Infantry Regiment and later the division. Army planners favoured recruiting experienced skiers for the unit instead of trying to train standing troops in mountain warfare, so they recruited from schools, universities, and ski clubs for the unit.[ The 87th trained in harsh conditions, including Mount Rainier's 14,411-foot peak, throughout 1942 as more recruits were brought in to form the division.

Early on the 21st April the 10th Mountain Division sent ahead Task Force Duff, consisting of tanks, tank destroyers, engineers, a battalion of infantry, and the 91st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron under Brig. Gen. Robinson E. Duff, towards Bomporto on the river Panaro. A rapid advance along the narrow roads, bypassing all towns continued throughout the day opposed only by snipers and occasional machine guns. The task force was out of communication with the remainder of the division much of the time, but the entire division advanced as fast as possible in the wake of the spearhead. A steady stream of German prisoners from a great variety of units marched south unguarded alongside the northbound Allied columns. By 1600 the Bomporto bridge over the Panaro was securely held by Task Force Duff, and the engineers began to remove the unexploded demolition charges under the bridge. On the next day the task force again sped ahead, this time 24 miles to the town of San Benedetto Po; by 2300 the division was assembling on the south bank of the Po, using its own trucks and captured enemy vehicles to shuttle troops forward.

On the morning of the 23rd , General Hays prepared for a scratch crossing of the Po. During the morning fifty M2 assault boats with paddles were brought forward from the corps dump and dispersed along the south bank, A battalion of self-propelled 105mm howitzers and a battery of 5.5 -inch guns were ready to give supporting fire for the crossing, H-hour was set finally at noon, and preparations for the initial crossing by the 1st Battalion, 87th Mountain Infantry, were completed hastily. Though a murderous barrage from enemy antiaircraft guns was received in the assembly area a few minutes before the jump-off, the 1st Battalion paddled the 300 yards across the river on schedule and was followed immediately by the remainder of the 87th Mountain Infantry. The Germans resisted with artillery, machine-gun, mortar, and sniper fire at the and by 1745 the 87th Mountain Infantry established a bridgehead 2000 yards square on the north bank of the Po River. The 85th Mountain Infantry was over by 1800, and the 86th Mountain Infantry crossed during the night.

Due to the limited preparation time, the bridgehead was difficult to support or to supply but on 24 April engineer bridge crews began the construction of a pontoon bridge and a treadway bridge. A battalion of DUKWs reached the river early in the evening of the 23d and assisted with the later parts of the crossing. By the afternoon of the 24th a cable ferry was also operating , and light tanks and guns began to cross to the north bank. By dark the 10th Mountain Division also held a damaged bridge over the Mincio at Governolo and had expanded its bridgehead well beyond the latter river. American troops had broken the Po defence line; the situation was ripe for further exploitation as soon as the 85th Division had crossed.

The 85th Division had secured the line of the Samoggia on the morning of the 21st and started for the bridge over the Panaro at Camposanto in the afternoon. Shortly after dawn on the 22nd the 338th Infantry in the lead on tanks and trucks reached the Panaro; then the 337th Infantry passed through and battled against enemy antiaircraft and other troops in Camposanto. Although the vital bridge was secured before it could be demolished, clearing the town proved an all-day battle, even with the aid of the 6th South African Armoured Division on the right, the bulk of the regiment was not able to cross the Panaro until nightfall. All night the 337th Infantry pushed on, and by 1045, 23rd April, the 3rd Battalion reached the Po at Quingentole.

A line was established along the river to head off any escaping Germans, and the 85th Reconnaissance Troop moved on to Revere on the south bank of the Po and partially cleared the town, although the bridge was found to have been wrecked several days before. Not knowing that they had been beaten to the river, German forces were still streaming north . During the night one group tried to force a crossing but was driven away, and the next day the 88th Division also had some trouble at Revere with Germans who had infiltrated back into the town after 85th Division units moved out to assemble for the crossing at Quingentole. Further to the west, along the Po, on 23rd April Combat Command A arrived at Guastalla and Luzzaro to the west of the 10th Mountain Division , IV Corps now held all its stretch of the Po and even had one division over. The left flank of this penetration was protected until the 23d by Combat Command B, battling up Highway 9 and blocking the roads from the mountains. The Germans fought over the Panaro crossings east of Modena on the 22nd and the next day at the river Secchia to the west, where Combat Command B, driving nearly due west south of the Highway, was stopped. Modena itself was largely bypassed and left to the partisans to clear. On the 24t the 34th Division came up from Bologna and relieved the armour on Highway 9 . Farther to the left the Brazilian 1st Division emerged into the plain late on the 23d at Marano and Vignola and moved northwest along the foothills south of Highway 9.

II Corps

On 21 April, as Bologna was being cleared, II Corps struck north for the Po. Units in the centre ran into less difficulty than those moving up the right. The Panaro River was more strongly defended around Finale on the eastern boundary than it was in the direction of Camposanto. The 1 Fallschirmjager and 4 Fallschirmjager Divisions suffered heavy losses but successfully covered Tenth Army's flank as it retreated across the Po; the junction of Fifth and the British Eighth Army near Bondeno was effected too late for maximum success. Initially the 6th South African Armoured Division was to be in the lead, first to hold crossings over the Reno northwest of Bologna until relieved by infantry, then to take and hold the important road centre of San Giovanni, and thereafter to cover the entire corps front, followed by the 88th Division on the left and the 91st Division on the right. On the 21st the armour cleared the right bank of the Reno north of Bologna; after it had halted for the night the 88th Division passed through to take San Giovanni.

The following day the 11th South African Armoured Brigade on the east flank set out for Finale on the Panaro, and the 12 South African Motorised Brigade started for Camposanto on the west. Both units were held up by the Germans and the division did not get across the Panaro until the morning of the 23rd. Contact was made with the 6th Armoured Division of Eighth Army two miles east of Finale. II Corps now moved the South Africans to a zone of their own on the right flank running up to Felonica on the Po, which advanced elements reached on the afternoon of the 24th. In the last two days bridging the Panaro caused the South Africans as much delay as enemy opposition; part of the division crossed at Camposanto on the 23rd and other elements used the 91st Division bridge halfway between Finale and Camposanto. A division bridge was opened at Finale on the morning of the 24th, and the rest of the 6th South African Armoured Division then moved up to Felonica preparatory to crossing the Po.

To the left the 88th and 91st Divisions had already reached the river Po and were putting their leading elements over. The 88th Division cleared San Giovanni on the night of 21-22 April and reached the Panaro east of Camposanto in the middle of the afternoon on the 22nd. The South Africans had arrived at the river a little to the west some three hours previously; over in the IV Corps zone the 10th Mountain Division had already crossed, and the 85th Division was clearing Camposanto preparatory to crossing. Elements on the right, however, had not yet come up to the Panaro. In the zone of the 88th Division the 913th Field Artillery Battalion laid down a heavy curtain of fire to smother a small band of Germans north of the river; the 2nd Battalion, 351st Infantry, then moved over on a semi -demolished bridge, and a short distance to the east the 1st Battalion crossed on improvised rafts of timbers and doors.

On the 23rd the 350th Infantry passed through the 351st Infantry and with the 349th Infantry on the right dashed towards the Po. The 349th Infantry reached the Po north of Carbonara at 2000 and fanned out along the river bank to gather in the thousands of German stragglers in the vicinity. The 350th Infantry, shifting over to the left astride Highway 12, arrived at the river a little later. The 88th Division had closed in on the Po where the Germans were assembling their shattered forces for the escape across the river. The prisoner haul reached its peak in the 88th Division zone. From noon on 23 April to noon on 25 April, approximately 11,000 prisoners were taken, the bulk of them from the 65th Grenadier, 305th Grenadier, and 8th Mountain Divisions. These included the first German division commander taken during the whole Italian campaign, Major General Von Schellwitz, commander of the 305th Grenadier Division. By midnight of the 22nd April advanced elements of the 363rd Infantry, riding tanks and tank destroyers, reached the Panaro. There the infantry dismounted from the vehicles and crossed the river by foot bridges halfway between Finale and Camposanto while the armour and trucks went around to the Camposanto bridge. Movement beyond the Panaro was unopposed until a few miles southwest of Sermide, where the American forces lost two tanks to a self-propelled gun in a sharp fire fight. The Germans disengaged thereafter and apparently got away across the Po, for no more resistance was encountered as the 363d Infantry moved north to reach the river banks near Carbonara west of Sermide at 0800, 24 April.

On the division right the 62nd Infantry was held up by the battle of Germans and South Africans below Finale and also by orders to gain contact with Eighth Army; when the 6th South African Armoured Division took over the right flank of II Corps, two battalions of the 362nd Infantry were entrucked and across the Camposanto bridge to continue the attack north, closing in at Sermide about noon on the 24th. By the end of 24 April ,the Fifth Army, large parts of which had already crossed the Po, held the south bank of the river on a line extending for about 60 miles from the Taro River to the Eighth Army boundary at Felonica, with the 1st Armored, 10th Mountain, 85th, 88th, 91st, and 6th South African Armoured Divisions along the banks from west to east. Since the 21st April these troops had covered 40 miles from the mountain to the river through the smashed centre of the German armies. Driven to desperation, the Germans had taken to the roads in daylight and had thus laid themselves open to Allied air attacks. Increasing numbers of abandoned vehicles and equipment attested to the disorganization in the German retreat Clear weather on the 23rd once more gave Allied planes free rein, German columns converging on the river crossings were blasted into shambles of wrecked and burning junk. In the period 21-25 April, the Fifth Army took approximately 30,000 prisoners at a cost of 1,397 casualties. Captured rear echelon personnel were commonplace — hospitals, bakeries in which the bread was still warm, a paymaster with his payroll, and personnel units. Though the bulk of the German forces managed to get across the Po, the loss in equipment augured ill for any extended stand on their part thereafter.

As they fled back across the Po, the shattered German armies in Italy were a shadow of their former selves. There now followed eight days of frantic efforts to escape a relentless pursuer, eight days of disintegration of leadership, organization, and the will to resist in the face of inevitable defeat. North of Bologna their centre was completely smashed, and the forces on either flank, though still in fair condition, were no longer attempting to give battle south of the river; they were concerned rather with efforts to prevent the spread of the penetration to the east or west while they made good their escape. The Fifth Army at the Po was nearer the Alpine exits than the enemy forces on either side. With the disintegration of German forces apparent. General Truscott ordered the attacking divisions to cross the Po as soon as possible and to drive as far as they could.

IV Corps

On the IV Corps front Infantry crossings were begun by the 10th Mountain Division on the 23rd in the face of determined though insufficient opposition, and by the 24th the operation was in full swing. The 85th Division put its first forces across the Po without firing a shot, established ferries, and placed assault barges in operation. Bridging the river thereafter was a mad scramble in which little went according to plan. The elaborate preparations made by the engineers before our attack began had been based on the assumption that II Corps would probably make the crossing with the 85th Division in the lead. Instead, three divisions of IV Corps arrived on the river bank ahead of any units of II Corps, and the 10th Mountain Division actually made the first crossing. On the morning of the 23d all readily available II Corps bridging equipment— assault craft for one regimental combat team and one M1 treadway bridge — was directed to IV Corps, but arrived piecemeal; the M1 bridge convoy started for Quingentole, too far to the east, but finally reached San Benedetto on the next morning. Work on this bridge was begun after noon on the 24th but was delayed until missing cables and ropes arrived. At 1930 the same day a heavy pontoon bridge was started three miles upstream at the site of a former floating bridge. Work proceeded rapidly during the night, and early in the morning, as the men began to slow up because of fatigue, two fresh companies were put on the pontoon bridge and a whole battalion on the treadway bridge. By 1230, 25th April, the treadway bridge was opened for traffic, and four hours later the pontoon bridge was open.

Both bridges, each over 900 feet long, were ready approximately twenty- four hours after beginning of construction despite handicaps such as inexperienced labour on the pontoon and the necessity of putting in double anchors and an overhead cable to hold the treadway in the swift, soft-bottomed river. Within forty-eight hours an armoured division, an infantry division reinforced with armour, and part of a II Corps division had passed over without incident. The burden of bridging first the Po, then the Adige and the Brenta, all three major rivers, placed a heavy load on the engineers of II Corps.

While the bridges were under construction the Fifth Army was already far north of the river. By Army orders on the 24th April, IV Corps on the left, employing initially three divisions north of the river, was to drive north on the axis San Benedetto-Mantua- Verona with the important Villafranca Airfield and the city of Verona as the main objectives. They would also dispatch strong, fast detachments north to the Alpine foothills where they would turn west to drive along the northern edge of the Po Valley through the cities of Brescia and Bergamo and block the routes of egress from Italy between Lake Garda and Lake Como. II Corps on the right was to move north along the axis of Highway 12, which enters Verona from the south, to seize the west bank of the Adige River from Legnano north to Verona. Full attainment of the objectives would block escape routes to the north between Verona and Lake Como and would place Fifth Army in position to assault in strength from Legnano to Lake Garda the last major defensive system left to the Ger-mans in Italy, the Adige River line. Everywhere in the Po Valley there were action and movement , the Germans were struggling to get out of the plain but disorganized in command and smashed by American planes; while seemingly moving here and there confusion, the Fifth Army was actually carrying out a masterful plan to hem the enemy into ever narrowing pockets. Although the constant shifting of units and the enormous extension of supply lines taxed Army supply facilities to a degree never before experienced in Italy, the advance did not suffer a major delay because of shortages. According to captured German officers., their plans of retirement had been based on the assumption that even in the event of a breakthrough the Fifth Army would have to stop at the Po to await supplies before resuming the offensive.

By 24 April IV Corps had Combat Command A, the 10th Mountain Division, and the 85th Division in line along and across the Po and the 34th Division, the Brazilian 1st Division, and two detached regiments of the 92nd Division protecting its left flank from Highway 9 south. The 10th Mountain Division had put all three of its regiments, including artillery, across the Po on the 23d and 24th, On April 23, 1945, Brigadier General Robinson E. Duff, Assistant Division Commander of the 10th Mountain Division, was wounded. Colonel William O. Darby took over and “task force Duff” became "Task Force Darby". Darby had been with the first United States combat troops sent to Europe the 34th Infantry Division, a National Guard unit known as the Red Bull. During its stay in Northern Ireland Darby became interested in the British Commandos. On June 19, 1942, the 1st Ranger Battalion was sanctioned, and Darby was put in charge of their recruitment and training under the Commandos in Achnacarry. Many of these original Rangers were volunteers from the 34th.[7][3] In November 1942, the 1st Ranger Battalion made its first assault at Arzew, Algeria, Darby took part in the Allied invasion of the Italian mainland in September 1943, and was promoted to full colonel on December 11. The three existing Ranger battalions were effectively wiped out - killed or captured - in the disastrous Battle of Cisterna during the Anzio campaign in early February 1944, after which they were disbanded.In March 1945, Darby returned to Italy for an observation tour with five-star General of the Army Henry H. Arnold.

Verona

While “Task Force Darby” waited on the completion of the corps bridges, patrols and partisans reported enemy withdrawals to the front during the night of 24-25 April. Shortly after midnight the 85th Mountain Infantry moved north to Villafranca Airfield, which it reached by the middle of the morning on the 25th. With no assurance of immediate support to the rear, the men of this regiment had marched almost 20 miles, most of it in darkness, through strange country, and without adequate maps. At dusk Task Force Darby caught up with the 85th Mountain Infantry and moved on cautiously toward Verona, to find upon arrival at 0600, 26 April, that the 88th Division had entered the city some eight hours before.

Verona had passed a number of tense hours before the Americans arrived. The German supreme command promised the bishop, Monsignor Girolamo Cardinale that the central area of Verona would be free from fighting and destruction, provided that the population abstained from any act of hostility towards the Germans, At the same time , the Germans placed explosive charges on all the bridges of the city, including two monumental ones (Ponte Pietra and Castelvecchio). With it strategic location on the road to the Brenner Pass, Verona had been a substantial military centre for the Germans, They had substantial magazines of explosives in the outskirts of Verona and the population feared that the retreating Nazis would detonate them . In Avesa above the city, the quarries of Mount Arzàn held the largest deposit of explosives in northern Italy. Hearing the rumours, a local priest Don Giuseppe Graziani rushed to the headquarters of the Platz Kommandantur and implored the German commander to cancel the order to blow up the powder magazine of the Arzàn or at least to allow a reduction in the amount of explosive in the magazine.

In the city of Verona a car with a German officer and some soldiers left the railway bridge, and the occupants began detonating the explosive charges. The railway bridge was severely damaged so as to make it impassable, the car then proceeded along the left bank of Lungadige, with the occupant systematically blowing up all the other bridges within a few minutes of each other Some of the modern bridges remained damaged but standing the two ancient ones crumbled, almost pulverized. After the bridges of Verona were destroyed, without warning the German soldiers blew up the ammunition depot of Corrubbio, in an old limestone quarries on the hill overlooking the town. A massive explosion hit the entire surrounding area. About 30 people were kilòref and msy house , destroyed, Meanwhile, up at Avasa, a human chain made up of eight hundred men and women, worked through the night to remove as many crates of TNT as possible from the Arzàn, transporting them to the meadow below the mountain. A spark and it would have meant death for everyone. At 6.15 a.m. on 26 April, the Germans blew up the Arzàn anyway , but after the heroic efforts of the population the night before , there were 35 thousand fewer crates of explosives and the tragedy was thus reduced by a collective action.

By the end of the 26th, Task Force Darby was driving along the east side of Lake Garda; with the 85th Mountain Infantry at Villafranca and the 86th Mountain Infantry resting at Verona, During the early afternoon Darby returned to Verona and then followed the route of his task force northwest from the city, arriving at Bussolengo about1600 hours. A wooden bridge crossing the Adige had been found intact in the vicinity of Bussolengo, so that infantry patrols of Task Force Darby had crossed the river and were patrolling the northern bank. A few German vehicles were intercepted trying to flee north ward on Highway 12. Darby recalled these patrols to the southern bank of the Adige and, in line with the division’s new objective, ordered one battalion of the 86th with supporting tanks to continue the drive west ward and by nightfall to seize Lazise on the southeastern shores of Lake Garda, thus sealing off a possible German escape route along the the eastern shores of Lake Garda. Task Force DARBY had not only spearheaded the second longest, 24-hour divisional advance of the campaign (22.5 miles), but also had successfully cleared all enemy personnel from the area of its advance and had physically occupied a thirteen-mile front along the southern bank of the Adige from Verona to Bussolengo [and overland] to Lazise.

The 85th Division had by this time crossed the Po at Quingentole by rafts, DUKWs, and assault boats on 24-25 April, and held the hills above Verona. On the left the 91st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron screened the left flank of the 10th Mountain Division.

South of the Po

Although Fifth Army was primarily occupied in driving north as swiftly as possible, it could not overlook the sizable block of Germans left in the mountains west and south of Modena. The main drive up Highway 9 to cut off these forces was made by the 34th Division, The 133rd Infantry took Reggio late on the 24th; then the 168th Infantry and the 755th Tank Battalion smashed a small garrison at Parma late on the 25th; the 135th Infantry raced for Piacenza, 45 miles away, and reached its outskirts by the afternoon of the 26th. Here an enemy garrison of Italian SS and German troops held out until the 28th. In less than three days the 34th Division had pushed its forces 80 miles from Modena to the Po crossings at Piacenza and had split the enemy right in two. To the south of the thin divisional line — "40 miles long and 40 feet wide" — were the German 148th Grenadier and the Italia Bersaglieri Divisions, trapped at the edge of the Apennines south of Highway 9; to the north was the 232nd Grenadier Division, which had managed to cross the highway west of Parma ahead of the 34th Division and assembled to defend itself in the Po loop south of Cremona . The 34th Division, strung out as it was between three relatively intact divisions, was in no enviable position, yet the very fact that we could get away with such a manoeuvre illustrates clearly the end of the German armies as an organized fighting force. The lack of communication between the three German divisions and their low state of morale at enabled the 34th Division during 26-28 April to block off the Piacenza escape route on the northwest, and at the same time to devote the 133d and 168th Infantry to the systematic destruction of the 232nd Grenadier Division south of Cremona. By the end of the 27th, after two days of attack from all sides which inflicted heavy casualties in men and material, the 232nd Grenadier Division was finished as a fighting force when a regimental commander surrendered with his whole command; only part of the division had gotten across the Po. At this point the 34th Division was moved out of the Highway 9 zone, and the remaining enemy divisions were left to surrender to the Brazilians a few days later. The Brazilian 1st Division, after emerging into the Po Plain south of Modena on the 23rrd, swung to the northwest at the very edge of the Apennines parallel to and south of Highway 9 and the 34th Division. The change in direction pinched out the 371st Infantry, which reverted to Fifth Army control and moved to Modena to guard prisoners on the 26th. Once the plain was reached advances were rapid against slight opposition until the 26th, when the division reconnaissance units and the 200 partisans working with them ran into elements of the German 148th Grenadier and Italia Bersaglieri Divisions at the town of Collechia south of Parma. A serious fire fight developed, but the town was cleared with a bag of 300 prisoners after reinforcements were brought up. This engagement was the beginning of the end of the two German divisions trapped south of Highway 9. After failing in an attempt on the 27 th south of Parma to break through the 34th Division to the Po the 148th Grenadier Division pulled back up the Taro Valley into the hills around Fornovo. Heavy fighting continued there for two more days as the Brazilians mopped up the Germans. At 1800, 29 April, the commanding generals of both the 148th Grenadier and Italia Bersaglieri Divisions formally surrendered to the Brazilians. By the 30th over 13,000 prisoners, 4,000 horses, and 1,000 trucks were taken. Meanwhile the Brazilian 1st Division had assumed the 34th Division zone north of Highway 9 on the 28th; its 1st Infantry advanced to Piacenza, and a battalion of its 11th Infantry moved up to finish off the pocket south of Cremona.

II Corps

As IV Corps was gathering at the Po on 23 April, II Corps units were moving across the Panaro, still some 20 miles south of the Po. The following day II Corps arrived at the Po three divisions abreast and immediately prepared to cross. On the left the 88th Division moved over the river at Revere, using the wrecked railroad bridge in addition to assault craft, DUKWs, LCVs, and Alligators. The Germans made ineffectual efforts in the night to hinder the consolidation by scattered bombing and strafing. The next morning the 88th Division started the 20-mile march for Verona by foot, jeeps, captured vehicles, and bicycles. At 2210, after a march of 40 miles in 16 hours, the 2d Battalion, 351st Infantry, and light armour reached the south outskirts of the city; by daylight on the 26th the city was cleared. Late on the 24th the 91st Division crossed the Po at Sermide and pushed toward Cerea and Legnago on the river Adige. At Cerea the 361st Infantry fought a night-long engagement with a large German column of trucks and artillery trying to force a passage north through the town. Fortunately the Germans were more confused than the 361st Infantry, and by morning they had been cut to pieces with appalling losses in equipment and personnel. Movement from Cerea to the Adige was without further incident. The 2nd Battalion, 363d Infantry, cleared Legnago by noon on the 26th and began crossing the Adige immediately.

Farther to the right the 6th South African Armoured Division established a bridgehead over the Po at Felonica on the 25th. By 26 th April Fifth Army had split in two the German forces in Italy. In IV Corps the 10th Mountain Division blocked off routes to the Brenner between Lake Garda and Verona; the 85th Division on the corps right was moving through Verona to at- tack the Adige Line defenses in the hills north of the city; and on the left Combat Command A was racing north past Mantua toward Brescia with the intention of swinging northwest toward Como. South of the Po River, as Combat Command B continued mopping up north of Parma, the 34th Division and the Brazilian 1st Division had cut across the path of retreat for two enemy divisions on the line Piacenza-Parma.

II Corps now held the line of the Adige from Verona south to Legnago with the 88th and 91st Divisions, and crossings were in progress. The 6th South African Armoured Division on the II Corps right, with two brigades still to cross the Po, was advancing to Adige crossings south of Legnago. Along the Ligurian Sea the troops under the 92nd Division, after reducing the last Gothic Line position on the 25th, were racing toward Genoa. New orders from General Truscott on the 26th directed Fifth Army to cut off and destroy the German forces in northwest Italy and to assist Eighth Army in the capture of Padua. The main attack was to drive across the Adige and through the defences of the Adige Line before they could be manned by the Germans. II Corps was to swing eastward on the axis Verona- Vicenza to assist Eighth Army in the capture of Padua and to block escape routes to the mountains which might be used by enemy forces along the Adriatic. IV Corps was to send one di- vision north along the eastern shores of Lake Garda on the axis Verona-Trent-Bolzano toward the Brenner Pass exit and into the’ ‘Central Redoubt" frequently mentioned in enemy propaganda as the site for the last-ditch stand of the beleaguered German armies; the 1st Armored Division was to continue its drive northwest along the edge of the Alps to Lake Como; and the Brazilian 1st and US. 34th Divisions were to finish the clean-up job south of the Po.

The Fifth Army fanned out to capture as many remaining Germans as possible in the Po valley and to forestall the formation of the Tyrolean army reportedly being organized in the mountains. Neither the Adige River nor the nearly unmanned defences on its eastern bank proved a serious obstacle. Allied units could practically at will drive across country 20 miles a day . The Germans still tried to get as many troops as they could out of the valley to the comparative safety of the Alps, and single units often fought fiercely to cover their retreat; in no case, however, did those actions constitute a real threat to the Allied advance . Not infrequently our rear columns found places taken and cleared by leading elements again in the hands of the enemy. The simple fact was that no front lines existed, and the countryside swarmed with Germans from a wide variety of units, many apathetically awaiting capture and others attempting to pass unobserved through our thin lines and into the mountains. II Corps crossed the Adige between 26-28 April on a broad front of three divisions, each operating in several high-speed motorized and armoured columns. Vicenza was cleared on the 28th after hard fighting by the 350th Infantry. The 88th Division, which had been travelling astride Highway 53, fanned out to the left into the hills and up the Brenta and Piave river valleys north of Bassano and Treviso. The 85th Division, attached to II Corps on 30 April, took over the job of moving up the Piave Valley on 1 May; the 88th Division was thus enabled to concentrate its efforts on the Brenta Valley and the roads leading into it preparatory to continuing the advance on Innsbruck via the Brenner Pass. On the corps right the 91st and 6 South African Armoured Divisions drove east, the 91st Division reaching Treviso on the 30th. The South Africans had made contact with Eighth Army at Padua on the 29th, reaching the end of the Fifth Army zone; the advance was halted, and while the 91st Division continued to mop up enemy resistance in its area the South Africans assembled and started movement to the Milan area.

Eighth Army

The Eighth Army on the right, reached the Po on the 24th. Efforts to trap the enemy south of the Po by a junction with Fifth Army at Bondeno were not entirely successful, for the 1st and 4th Parachute Divisions, the 26th Panzer Division, and the 278th Grenadier Division somehow managed to get across the Po in relatively good condition but with little armour or artillery. German losses in men and equipment before Eighth Army south of the Po were very large. On the 25th the Eighth Army crossed the Po, and on the 27th the Adige. The Germans offered fierce resistance before relinquishing Padua to Indian troops and Venice to the 2 New Zealand Division, both on the 29th. The Eighth Army had now virtually destroyed the German Tenth Army and was driving rapidly toward Austria and Yugoslavia. The 6th Armoured Division seized a bridge over the Piave southwest of Conegliano on the 30th, and the New Zealanders established a bridgehead farther south. At 1500, 1 May, the 2nd New Zealand Division established contact with troops of the Yugoslavian Army at Monfalcone less than 20 miles northwest of Trieste. By 2 May, when hostilities ceased, the armour had fanned out northwest and east of Udine, and the New Zealanders had entered Trieste at 1600, there to mop up the last embers of German resistance.

Endgame

In the centre IV Corps units breached the Adige Line and raced to block off the exits from Lake Garda to Lake Como. On the 26th the 85th Division simply walked through the Adige Line north of Verona The 10th Mountain Division moved up the east shore of Lake Garda toward the exits of the Brenner Pass and in the demolished tunnels of the east lake shore drive ran into the most difficult fighting it had experienced since the breakthrough in the Apennines.

On 28 April, the 86th Regiment passed through the 85th, but the advance that day was limited to five miles because the Germans had successfully blown the first of six tunnels through which the lake side road passed at this point. The attempts of the partisans to prevent possible demolition, had failed. On that side of the lake, the cliffs rose so steeply from the edge of the lake that the advance was continued by means of an amphibious operation . This operation caught the German Paratroops and SS men, who had been fighting us in this region, off balance, so that the remaining tunnels were captured intact on the 28th and 29th. On the morning of the 29th, Colonel Darby went forward by speedboat (to get around the blown-out tunnel) and then by jeep to investigate the progress of the 3rd Battalion of the 86th, which had been held up by German fire into the fifth tunnel by 88mm self-propelled at the head of Lake Garda. Five Americans were killed and approximately fifty wounded by a German shell that exploded ten yards into the tunnel. General Hays joined Darby in a speedboat that to return to the division command post. In a matter of seconds, a shell burst in the water about fifty yards to rear of the boat, followed by seven more , fortunately they all missed. Throughout the 28th and 29th German vehicles continued fleeing northward on Highway 45,protected by one of seven road tunnels on the eastern shore of Lake Garda. At 2400 hours on 29 April, Darby took charge of an amphibious operation which involved sending Company K of the 85th across the lake in DUKWs to seize Gargnano and thus cut the escape route up Highway 45. This operation was successfully completed by 0200 hours on 30 April. Later in the morning Darby and other division officers crossed the lake to inspect Mussolini's mansion and estate on the outskirts of Gargnano.

By noon on 30 April the 10th Mountain Division had two columns closing in on the town of Riva at the head of the lake. The advance was slow for the 86th on the east side of the lake, however, because the Germans were able to direct fire from the 88mm guns in the roads from the hills and mountains above the head of the lake. Nevertheless, the 86th had taken Torbole and was pushing on toward Riva, just three miles away. About 1400 hours on 30 April, Darby went forward by DUKW to Torbole. After landing, Darby walked immediately to the 86th regimental command post close to the waterfront. For about half an hour he conferred with the regimental commander and his staff, about three minutes before Darby concluded this conference, a single 88-mm. round was heard bursting somewhere nearby in the town. Darby left the room and walked outside, intending to take a jeep back along the eastern shore to examine the road and tunnels. Two or three of the initial shells landed along the waterfront, but just one of those produced the small fragment that killed Darby instantly .Desperately bad luck considering the war had such a short time left to run , Also desperately unlucky were 25 soldiers from the 10th Mountain Division who drowned at Lake Garda on the night of 30 April, when their amphibious craft (DUKW) sank in one of the squalls typical of Lake Garda.

In the western part of the Po Valley IV Corps concentrated on the German LXXV Corps under Lt. Gen. Ernst Schlemmer, a still intact block of two divisions (34th Grenadier and 5th Mountain Divisions) which had been guarding the Franco-Italian frontier and was now withdrawing northeast past Turin under constant partisan attack. On the 26th Combat Command A started northwest and rolled through Brescia and Bergamo to Como on the western arm of Lake Como two days later; en route it met only scattered opposition. Combat Command B followed across the Po on the 27th, drove to the Ghedi Airfield south of Brescia, and then swung west on an axis south of and parallel to that of Combat Command A. On the 29th, the same day that Troop B, 91st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, found Milan in the hands of the partisans, The 1st Armored Division consolidated positions north and east of Milan: Combat Command A on the right, Combat Command B on the left, Task Force Howze in the centre, and the 81st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron patrolling on the left flank. By the 29th this latter unit had pushed to the Ticino River, which might prove a good line on which to hold LXXV Corps. The next day a IV Corps task force formally occupied Milan. In three days, the 1st Armored Division facing only scattered opposition, had driven a wedge between German forces in the mountains and those still on the plain. In order to strengthen the long, thin line the 1st Armored Division had drawn across the top of the valley and to assist in mopping up the large enemy forces west of Milan, the 34th Division moved swiftly across the Po and toward Bergamo on the 28th, followed by the Legnano Group on the 30th to Brescia. On 1 May the 34th Division relieved 1st Armored Division reconnaissance elements on the Ticino River northwest of Milan. It then took Novara west of the Ticino the next day against no opposition; elements were also sent northwest 30 miles to Biella at the edge of the western Alpine chain. Drawing the noose across the top of the valley onthe line Ticino River-Novara-Biella left surrender as the only alternative to LXXV Corps, which was concentrating northeast of Turin and south of the 34th Division.

Conclusion

The Fifth Army's long thrust straight north from the Apennines to Lake Garda and thence across the top of the valley to the east and west had first split the German armies in Italy in two and closed the door of retreat to the Alps. In the east the British Eighth Army chased the Germans north along the Adriatic coast; in the west the 92nd Division tore along the Ligurian coast to Genoa; and south of the Po the Brazilian 1st Division and for a while the 34th Division rounded up enemy forces caught in the Apennines. The latter project was completed successfully by the 29th, and on the next two days the Brazilian 1st Division fanned out to Alessandria and Cremona. On 27th April, in Genoa 4,000 troops commanded by General Meinhold, had surrendered to the partisans the day before, but the port garrison and a detachment of marines on top of a hill overlooking the harbour held out until the next day. Beyond Genoa on the right the 442nd Infantry moved north of Genoa into the Lombardy Plain to capture Alessandria and its garrison of 3,000 men on the 28th. There they linked up with the Brazilians. Contact between the 92ndd Division and IV Corps was made at Pavia. Turin was cleared by the partisans on the 28th and was reached by American troops on the 30th. On the same day the 473d Infantry met French colonial troops on the coast. By that time the Germans in northwest Italy were surrendering on every side.

On 2 May hostilities in Italy ceased in accordance with terms of unconditional surrender signed by representatives of General Vietinghoff, Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Southwest, at Caserta on 29 April. The 20 month Italian campaign had finished with a final, smashing offensive which in 19 days reduced the Germans into a fleeing rabble with neither defences, organization, nor equipment