“ The Drowned and the Saved” – a short walk down Plattenstrasse in Zurich

Having written extensively about Stolpersteine in Milan, I did not expect to find one in Zurich. On a weekend vacation in Zurich to see Christmas Markets and the FIFA Museum, I was staying in the district of Zurich University on Plattenstrasse. I was actually on the way to look for Albert Einstein’s former residence , which was supposed to be about 15 minutes’ walk from the hotel passing along the length of Plattenstrasse . It is a pleasant leafy road ( well it would have been leafy if not in December ) with a number of very well-kept Swiss schools, University buildings and substantial villas. Towards the end of Plattenstrasse at the junction with Steinwiessstrasse. I spotted a familiar square on the pavement , as in the name I literally “stumbled” across it. Well not in the actual sense since Stolpersteine do not pose a tripping hazard. Anyway I did some research and uncovered the sad story of Walter Kölliker. Walter was a Swiss citizen, stripped of his nationality who died stateless in the Nazi concentration camp Sachsenhausen having been betrayed by a key associate in the German Communist Party ( KPD) . If Walter’s story is depressing , a bit further down the same road is a rather mote inspiring story of the role in which Switzerland and more strangely Turkey played in saving German Jewish academics. And I found Einstein’s House in the end. I borrowed the title of Primo Levi’s book for this one. “The Drowned and the Saved”- I think you can see why.

Stolpersteine for Walter Kolliker

Walter Kölliker was born on September 20, 1898 in Zurich. He spent his youth in Männedorf, a small city on the shores of Lake Zurich. He attended the Literargymnasium in Zurich. During his high school years, he decided to become a pastor and spent two semesters at the Faculty of Theology at the University of Geneva, then enrolled at the University of Zurich at the beginning of October 1918. In the course of this semester in Zurich, it soon became clear to him that he did not want to spend his life as a preacher, but to live the gospel. After his expulsion on 23 April 1919,he saw his future as a working person and therefore moved to the "Alte Vogtei" commune in Herrliberg where he worked as a farmer. as an active pacifist and refused military service in the Swiss army, which is why he was sentenced to three weeks in the district prison in Meilen. After a short stay in the Netherlands in 1923 he moved to Jessen, in the Prussian Province of Saxony. There he ran a gardening business with a partner and married Charlotte Erna Bergmann (1905-1944) They had two sons. Hans Heinrich, (born 1924) died 1948 as a foreign legionnaire in Indochina, Karl Thomas (born 1926) who died in 2019 in Thurgau-

Walter Kolliker's former residence in Plattenstrasse Zurich

The couple separated in 1928 and Walter Kölliker stayed in Jessen, Charlotte moved to Berlin with their sons. In the same year Walter presented an application for naturalization in Prussia, which meant that he would be stripped of Swiss nationality (dual citizenship not being possible at that time). The reason for the intended change the fact that his life had moved to Saxony and that Swiss military compulsory replacement tax was putting a financial strain on him. Only after Walter’s outstanding tax claims in the Switzerland had been paid did the Zurich government council approve his request to cancel his citizenship in 1930. As a result of his Swiss Tax Debt, Walter Kölliker came under increasing pressure, not helped by the onset of the global economic crisis which ruined his horticultural business and at the end of 1930 he had to declare bankruptcy. Worse, in 1931 Walter was refused German citizenship, and the entire family became stateless. Walter Kölliker ended up working as a journalist in Halle working for communist daily newspapers. During this time he always visited his children again in Berlin. When Hitler came to power at the end of January 1933, his estranged wife, Charlotte made a request in Zurich for renaturalization for herself and their two sons. Because she was not informed about her husband's expatriation (which he immediately confirmed), the Zurich government council approved the application in July 1933.

Walter became KPD district leader of East Prussia. In November 1933 he was arrested because his associate August Laß turned stool pigeon for the Gestapo and betrayed 22 functionaries of the illegal KPD. Laß was editor of the Rote Fahne and the KPD press in Danzig. In the party he was known as "Helmuth". In May 1933, he took over the political leadership of the now illegal KPD in Danzig. Together with Walter Kölliker, he was to build up a new organization. Laß was arrested in Danzig on 4 November 1933 by a Gestapo commando from Königsberg and taken to East Prussia, first to Marienburg and then to Königsberg. Laß had with him a letter of recommendation from Kölliker to Rudolf Reutter, head of the of the Central Committee of the KPD. In the course of the interrogations, he agreed to work as a decoy spy in Berlin. On 18 November, Laß travelled to Berlin with two Gestapo officials and two members of the SA intelligence department and made contact with leading KPD functionaries. The Gestapo supervised the meetings and arrested 22 people. Among those arrested were Rudolf Reutter, the Reich Pioneer Leader of the KJVD, Hans Lübeck, whom Kölliker had sent to Berlin to warn against Laß, the chief treasurer of the KJVD, Ulrich Burien, and the Political Director of the Berlin-Brandenburg District Leadership, Lambert Horn. In addition, written material and accounts were confiscated and the KPD organization in East Prussia was smashed. In the end Laß caused 170 arrests and handed over almost the entire KPD organization in East Prussia to the Gestapo. For his betrayal, Laß had been promised immunity from prosecution and a job in Königsberg by the Gestapo. He tried to persuade his wife Wilhelmine to give up her work for the KPD. However, she handed over his letters to Herbert Wehner, head charge of the KPD in Berlin-Brandenburg. Excerpts were published in illegal KPD newspapers. Wehner recounted in his memoirs: " Laß had explained to his wife in a letter that he had been faced with the choice of dying or taking on this role. He decided to do the second because dying is hard, especially for a lost cause. “ Wilhelmine Laß emigrated to Moscow in December 1933 and at the end of April 1934, Laß joined the SS Laß as an expert on Marxist Organisations. Needless to say, he survived the war unscathed.

Walter Kölliker was arrested in November 1933 and sentenced to three years in prison.” For the following years he remained in the Rhine court prison (East Prussia) and in Stuhm Central Prison (West Prussia). From prison he applied for readmission to Swiss citizenship. The Swiss envoy in Berlin, Paul Dinichert, then reported to the Federal Police Department in Bern that Kölliker was therefore not naturalized in Germany because he “identified himself as a communist. “The agitator was anti-state.” Dinichert, however, assumed that Kölliker would be expelled after his release and “taken over” by Switzerland anyway. The head of the police department of the FJPD, Heinrich Rothmund, took the opposite view, justifying Kölliker’s exclusion from Switzerland. In a letter to the Berlin embassy, he argued that Kölliker's statelessness was based on "self-inflicted guilt" and that his readmission to Switzerland should be “excluded given his political stance,” since readmission was only an option “for people of good repute and politically irreproachable people”. Rothmund was notoriously still Head of the FJPD when he agreed to a suggestion by German officials yo add a “J” stamp to identify Jews on German passports. The Swiss apologised for that in 1995.

Walter Kölliker was taken from prison to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp (near Oranienburg).north of Berlin). He died there on June 6, 1938 at the age of 40.

After the end of the Second World War the Swiss Federal Prosecutor's Office from August 1946 provided the following information: "In October 1937, lawyer Dr. Anton Zublin in Zurich on behalf of Arnold Kölliker in Uetikon a.S. and, Pastor [Lily] Nigg-Kölliker, ( Walter’s father and sister) in Stein/AP, a request for entry and Residence permit submitted for the now stateless category candidate. We have at that time the cantonal statement and municipal immigration police in Zurich connected because of its presence in Switzerland from the political point of view Police were unwelcome.” That Walter Kölliker as a communist anti-fascist in the Switzerland was “undesirable” and met his fate in National Socialist Germany!”

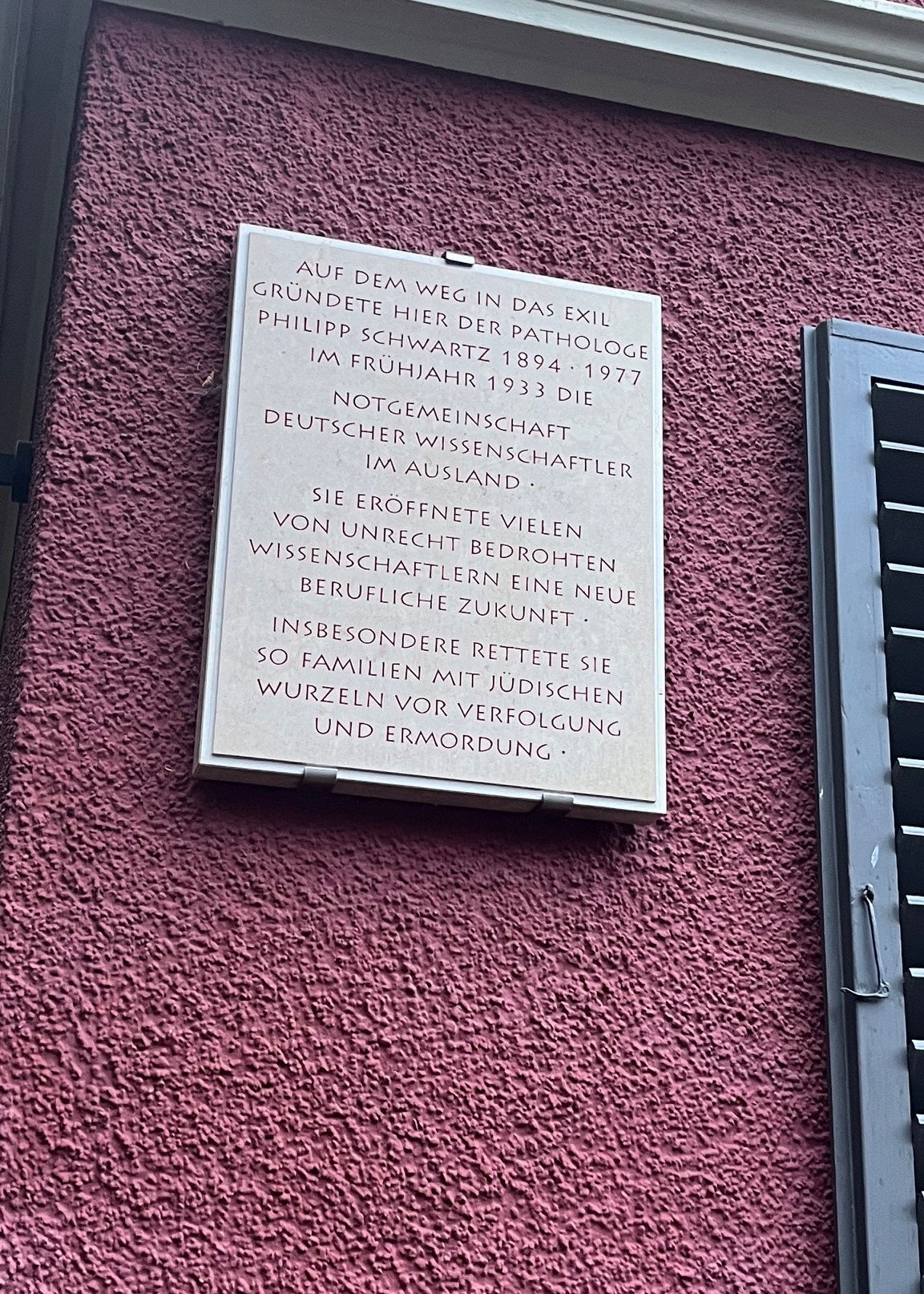

And just before , we start calling out the Swiss for being so bad, walking back to the hotel I come across another plaque on the wall. It has to be said that Zurich does commemorative plaques pretty well .This one commemorates the asylum the Swiss gave to eminent German Jewish Pathologist Philipp Schwartz.

Memorial to Philipp Schwartz in Plattenstrasse Zurich

Born on 19 July 1894 in Versec, Banat, Hungary, Schwartz studied medicine in Budapest and earned his doctorate there in 1919. In the same year, he became an assistant of Bernhard Fischer at the Senckenberg Institute of Pathology at the University of Frankfurt, where he worked for the next 14 years. He earned his Habilitation in 1923, became an associate professor in 1926 and a full professor in 1927.Following the Nazi takeover in 1933 he was dismissed from his university chair for being Jewish, and emigrated to Zurich. Schwartz’s father-in-law, professor S. Tschulok, was already in Switzerland having taken refuge after the 1905 Russian Revolution. Tschulok was a good friend of Albert Malche, professor of pedagogy who had prepared the report on the Turkish educational reform in 1932. In 1933, the young Turkish Republic was in search of civil servants capable of modernizing its old-fashioned and seemingly anti-reformist educational system. In the early 1930s, Istanbul Darülfünun, the only civil academic institution in the country, with its old-fashioned medrese system, was far from a dynamic and scientific educational institution. Furthermore, the antagonism of its academic staff towards Atatürk’s western policies was regarded as a hindrance to Turkish modernisation. Malche had been asked by the Turkish Ministry of Education to prepare a report on reforming the academic system in Turkey, he concluded that a new spirit and dynamism in higher education could be attained only by replacing the non-productive and old-fashioned academicians with modern, contemporary scientists who would be recruited from Europe

In Zurich Schwartz founded the Notgemeinschaft Deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland” (Emergency Association of German Scientists Abroad ) to help other refugees find new employment. This saw itself as a kind of self-help organization "regardless of race or religion" and in the next few weeks experienced an influx of more than a thousand university employees from all over the German Reich. From the outset, the declared aim was not to provide financial support, in the sense of a fund, but to provide jobs for job seekers. Especially in the early months, the Notgemeinschaft had to deal with a number of administrative problems. In some cases, German diplomas were not or no longer recognized abroad, and work and settlement bans prevented scientists from taking up new activities abroad. The first step towards the organization of the Notgemeinschaft was the formation of a Council of German Professors Abroad which informed the Notgemeinschaft about vacant positions at universities all over the world.

With the help of Malche , Schwartz established contacts with Turkish universities He was invited to Ankara for meetings with representatives of the government. He brought with him a list of names from the Notgemeinschaft, and provided these names to his Turkish counterparts. They wanted to select individuals with the highest academic credentials in disciplines and professions most needed in Turkey. Minister of education Resit Galip arrived with a complete list of professorships at the University of Istanbul. In his memoirs, Fritz Neumark, one of the émigré professors who went to Turkey, describes the day when Schwartz sat down with his Turkish counterparts as "the day of the German-Turkish miracle." In nine hours of negotiations, it was possible to put together a complete list of names for the professorships of the new Istanbul University—and all were members of the Notgemeinschaft!” At the end of the day, an overjoyed Schwartz was able to phone to Zurich from Ankara: "Not three, but thirty!" However, it was clear from the beginning that the German professors were meant to stay only until their Turkish pupils, i.e., their assistants and lecturers, could take over these positions. Therefore five-year contracts became the rule. Courses were to be taught as soon as possible in Turkish, using textbooks which had been translated into Turkish as well.

After five months ,Schwartz left Switzerland became director of the Department of Pathology at the University of Istanbul. Thanks to Switzerland and Turkey , Schwartz survived the Shoah and from 1953 he worked as a pathologist at the Warren State Hospital in Pennsylvania . In 1957 he was formally reinstated as a Professor (emeritus) at the Goethe University, but the university declined his wish to resume teaching due to his age.

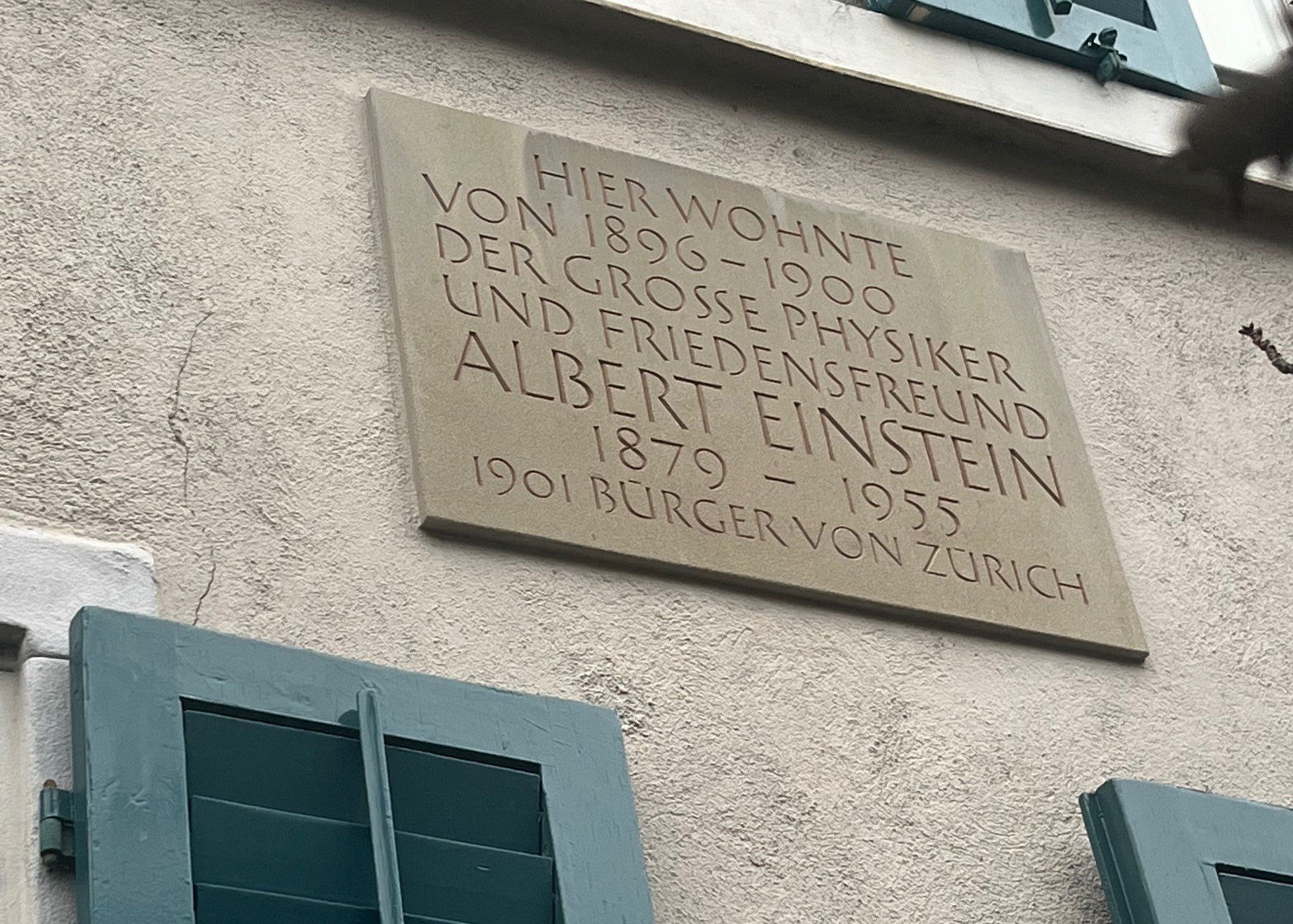

I was on my way to Einstein’s house and he also participated in the efforts to find help for German-Jewish academics. .After living in Italy , in Pavia ( of which more in another episode) in 1895 Einstein failed the entrance exam to the Polytechnic of Zurich ETH , in 1896 after some cramming at Aargau Cantonal School, he passed the Swiss Matura and finally got into ETH where he studied from 1896 to 1900 , obtaining a diploma in mathematics and science. He then commenced his famous career in the Patent Office in Bern. Einstein returned to Zurich twice as an associate professor in 1909 and as Professor of Theoretical Physics from 1912 to 1914. Einstein is recorded as living at different locations in Zurich , but between 1986 -1898 and 1899-1900 he lived at Unionstrasse 4,which is about 20 minutes stroll from ETH . If you want to see all of Einstein’s addresses in Zurich the ETH has published a handy map. Einstein was at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena when the Nazis passed the Enabling Act . On returning to Europe on 28 March 1933, he went to the German Consulate in Antwerp and renounced his German citizenship. A month later the Nazis started burning his books.

One of Einstein's former homes in Unionstrasse , Zurich

Memorial to Einstein

Einstein spent several months in Britain aided by the Academic Assistance Council, he met Winston Churchill, Austen Chamberlain, and Lloyd George. In September 1933, Sami M. Günzberg, a Jewish Turkish dentist, was attending an International Conference in Paris of the Union for the Protection of the Well-Being of the Jewish Population (OSE). There he met Einstein, the Honorary President of the organization, and together hatch a plan to help Jewish academics . Einstein wrote a letter to the Prime Minister, Ismet Inönü, “… I beg to apply to your Excellency to allow forty professors and medical doctors from Germany to continue their scientific and medical work in Turkey. The above mentioned cannot practice further in Germany on account of the laws… in granting this request your Government will not only perform an act of high humanity, but it will bring profit to your own country.” Günzberg would personally translate Einstein’s letter into Turkish, and with a cover letter of his own, submitted it to the Turkish Government. And although Einstein’s letter was addressed to Inönü.it was most likely meant for the President Ataturk. Inönü, replied

“Distinguished Professor, I have received your letter dated 14 November 1933 requesting acceptance by Turkey of 40 professors and physicians who cannot conduct their scientific and medical work in Germany anymore under the laws governing Germany now. I have also taken note that these gentlemen will accept working without remuneration for a year in our establishments under our government. Although I accept that your proposal is very attractive, I have to tell you that I see no possibility of rendering it compatible with the laws and regulations of our country. Distinguished Professor, as you know, we have now more than 40 professors and physicians under contract in our employ. Most of them find themselves under the same political conditions while having similar qualifications and capacities. These professors and doctors have accepted to work here under the current laws and regulations in power. At present, we are trying to found a very delicate organism with members of very different origins, culture and languages. Therefore I regret to say that it would be impossible to employ more personnel from among these gentlemen under the current conditions we find ourselves in. Distinguished Professor, I express my distress for being unable to fulfill your request and request that you believe in my best sentiments."

On the face of it Inönü's letter appears to have closed the doors to Einstein's plea. He refers to the fourty academics already negotiated by Schwartz. Fortunately matters did not end there, before the end of hostilities in Europe Turkey, had saved not just 40 as originally agreed to by Schwarz and the additional forty mentioned in the Inönü letter. Over 190 intellectuals had been saved from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia . Because of Turkey's influence at least one needed professional, dentistry professor Alfred Kantorowicz, was liberated from a nine-month incarceration in a concentration camp and allowed to proceed with his family to Istanbul.

It might be reasonably concluded that at the time, the Turks were not necessarily motivated by humanitarian instinct , but rather that émigré German academics “were hired because of their promise as intellectual mediators for the promotion of Europeanness in the host country” and were welcomed in Turkey, not as Jews (or Germans), but as Europeans”. The employment of academicians expelled by t Nazi Germany had another benefit since these individuals were unlikely to be Nazi spies or saboteurs. In August 1938 Turkey imposed an absolute ban on Jewish entrance into the country, even for transit passage purposes. Apparently, increased concerns about Jewish refugee problems in the wake of the Evian conference held in July drove the Turkish government to institute a more comprehensive and strict policy. The ban on the entrance of Jews from German-controlled Europe, even for transit passage purposes, by the August 29, 1938 decree might support the assumption that Turkish policy towards persecuted, Jews was not intended to help or rescue them, unless they could be beneficial to Turkey. Possibly to Turkish officials, these academics were neither Jews nor Germans, but Europeans who, they believed, could bring expertise to the country and establish a modern tertiary educational system.

In the end whatever the motivations, the Swiss gave Schwarz asylum and from Zurich , with Einstein’s assistance he was able to initiate his German Turkish Miracle and save more than a hundred lives.

Walking back the two hundred metres from Einstein’s house to the hotel, on the tranquil Plattenstrasse , there are two memorials , Walter Kolliker was the “Drowned” and died in Sachsenhausen, Philipp Schwartz was the “Saved “and died in Fort Lauderdale. Bad Swiss or Pragmatic Swiss, Pragmatic Turkey, or humanitarian Turkey, I leave that for you to consider.

In 2015, the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the Federal Foreign Office chose to name the programme they launched after him: the Philipp Schwartz Initiative. The programme allows researchers who are subject to significant and continuous personal threat in their country of origin to continue their work at German universities and research institutions.

Design Hotel Plattenhoff is on Plattenstrasse expect Zurich prices but very comfortable