Missing from the War Memorial by David Roberts

(c) Gea Grevnik

Ernest Barlow is buried at the Commonwealth Cemetery at Mook in the Netherlands ( Plot IE2) he is also commemorated on a memorial close to the place he died at Driel in the Netherlands. His tombstone in the cemetery shows his name, rank and date of death with no cross or emblem. He is recorded as being son of Sigmond and Stephanie Baruch, of Oporto, Portugal. Nobody can be blamed for not realising he had a connection with Buxton and so he is not recorded on any Buxton War memorials either on the own War Memorial or at Buxton college . However under the name of Theodor Ernest Baruch, Ernest Theodore Barlow was another German Jewish refugee boy who attended Buxton College in the 1900s. His journey took him from the German town of Worms on the Rhine to Buxton and then back to the Rhine at Driel where he was killed by a German bullet, wearing a British uniform. .

Ernst Theodor Baruch had the misfortune to live in interesting times. He was born in the city of Worms o on 29 January 1920. Worms is a port on the left (west) bank of the Rhine River, just northwest of Mannheim. In 413 CE it became the capital of the Burgundians, who, after disputes with the Romans, rose in revolt in 435 against the Roman governor Flavius Aelius. He called upon his Hun allies, who destroyed the city in 436. The Hun destruction of Worms and the Burgundian kingdom inspired heroic legends in the epic poem Nibelungenlied (c. 1200). Rebuilt by the Merovingian kings, Worms became a bishopric about 600 and a favourite residence of the Carolingian and Salian emperors. The bishopric (secularized in 1803) grew steadily in temporal power and territory, particularly under Bishop Burchard I (1000–1025), and Worms became a free imperial city of the Holy Roman Empire in 1156, remaining free until 1801. It was mainly famous for the Diet of Worms in 1521.

The year after Theodor’s birth , the city saw the 400th anniversary of the Diet of Worms and widespread celebrations at the Luther monument. The following year, the first local branch of the NSDAP was founded by Hans Hinkel, a native of the town. He was later expelled from the Rhineland and gravitated to Munich where he later participated in Hitler’s beerhall putsch.

Ernest Theodore’s father, Sigmund Baruch was the fourth son of the mill owner and councillor of commerce Moritz Baruch The family owned the "Nibelungenmühle", a feed mill which was managed by Theodor’s uncles Albert, Rudolf and Otto Baruch. After studying law, Sigmund ran a law practice in Worms, at Martinsgasse and from 1931 Moltke-Anlage 8, where the family also lived. the family also lived. The Jewish community of Worms claims to be the oldest in Germany and to have existed since the earliest Christian era, although the first authenticated mention of it was in 588.

The Niebelungmuhle - Worms

Tonialsa, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

At the time of Theodor’s birth, Worms was under French Military occupation. When the German government had sued for an armistice in October 1918, the French marshal Ferdinand Foch insisted on bridgeheads over the Rhine and to securing the river as France's new eastern border. Article V of the armistice of 11 November 1918 stipulated that the Allied armies should occupy the left bank of the Rhine The British occupied the bridgehead at Cologne, with the Belgians on their northwest flank, and the Americans occupied Koblenz. The French occupied Mainz and controlled the largest part of the Rhineland, including Worms with a huge occupation army of 250,000. In the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June, the French obtained a double guarantee of French security: through the demilitarization and a fifteen-year occupation of the Rhineland with its bridgeheads.

The Rhine at Worms -1900s

The end of 1923 saw a stabilization of the German currency that paved the way for financial reform and the rescheduling of reparations through the Dawes Plan. French problems with the continued occupation of the Ruhr led to the withdrawal of their forces by August 1925, paving the way for a more comprehensive security treaty for the states of western Europe. The Locarno Treaty of October 1925 included the Rhineland Pact, in which France, Britain, Belgium, and Italy agreed to maintain the inviolability of both German and French borders, and a demilitarized zone in the Rhineland. American troops were withdrawn in February 1923. British troops were then transferred to the Koblenz bridgehead and had their headquarters at Wiesbaden. Pressure from the German foreign minister Gustav Stresemann coupled with Anglo-French difficulties in maintaining the occupation, and the further rescheduling of German reparations under the Young Plan led to a partial military withdrawal in 1929 and all foreign troops had gone by 1930, five years before the originally agreed-upon date. Ultimately, the Allies Rhineland policy had done little to serve the interests of German democracy or their own security . As the last French occupation troops finally left the Rhineland, celebrations took place, the Rhineland remained demilitarised. . In 1932, Hitler turned up at the Alzeyer Stadium in the city and spoke to a crowd of 30,000.

With the French gone, things started to go rapidly downhill for the Jewish population .Industrial cities in the Rhineland, were traditionally strong in their support of left -wing parties, the KPD or SPD and became the centre of violent conflicts between the Nazis and their opponents. Shrove Tuesday ( 28 February ) 1933, saw bitter street fighting in the city between the Nazi SA and their opponents, ahead of the German Election on 1st March. The village Ohlendorf outside Worms became the site of one of Germany’s first concentration camps. Opened on 6th March, the Nazis illegally detained hundreds of local communists and socialists in the camp. With the Nazis new controlling local government and the police and a concentration camp set up nearby, Worms no longer seemed a safe place to be.

In 1933. 160 jews left Worms for elsewhere in Germany or abroad, and the once sizeable Jewish community diminished. The city also began to rewrite its historical heritage. Instead of promoting its Jewish sights, the city started to attract admirers of Luther, German Emperors and the Nibelung.

As the Jewish population declined in 1934, the 900th year of the first Worms Synagogue was commemorated. Letters from the Jewish world streamed in, from Budapest to New York and from many German-Jewish communities. They reflected the importance of Worms to the Jewish world because of its long-lasting tradition and resilience. Leo Baeck, head of Germany’s Jewish community, who held the main speech in June 1934, underlined: “Nine centuries of such a house of prayer means also fatherland. A covenant was created: between this space and fatherland, between home country and spirituality.” The celebration did not even get a mention in the local newspaper.

With the situation deteriorating the Baruch family joined the exodus abroad. Sigmund and his wife Stefanie together with Ernst Theo Sigmund moved to Oporto (Portugal) in 1934. However, they are still listed in the Worms directory in 1937 their police deregistration took place in 1939 with destination to Porto-Fez (Portugal).Daughter Gertrud was first in Portugal, possibly helping the rest of the family to emigrate to Portugal. The family mill was sequestrated and subsequently “aryanised”.

His parents sent Ernest Theodore to school in England as a boarder at Buxton College. The headmaster, Mr Arthur Mason was helping refugees from Germany to study there. Ernest's home visits now included the voyage from Liverpool to Vigo in Spain, the nearest Spanish port to Porto, about two hours train ride away. He is recorded as a passenger on the “Orbita" from Liverpool to Valparaiso , with a stop at Vigo. His address is given as the college Buxton. Ernst Theodor left Buxton College in the summer term of 1935. After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, it was difficult for him to get back to visit his family in Portugal and he seems to have remained in the UK.

At dawn on 7 March 1936, nineteen German infantry battalions marched into Rhineland, violating Articles 42 and 43 of the Treaty of Versailles and Articles 1 and 2 of the Treaty of Locarno.] They reached the river Rhine by 11:00 a.m. and three battalions crossed to the west bank of the Rhine. At the same time, Baron von Neurath summoned the Italian. British and French ambassadors Baron Bernardo Attolico, Sir Eric Phipps and André François-Poncet to the German Foreign Office in Wilhelmstrasse to hand them notes accusing France of violating Locarno by ratifying the Franco-Soviet pact and announcing that as such Germany had decided to renounce Locarno and remilitarize the Rhineland. The reaction in Britain was mixed, but they did not generally regard the remilitarization as harmful. Lord Lothian famously said it was no more than the Germans walking into their own backyard. No public meetings or rallies were held anywhere in protest at the remilitarization of the Rhineland, and instead there were several "peace" rallies where it was demanded that Britain not use war to resolve the crisis. an increasingly large segment of British public opinion had become convinced that the Treaty of Versailles was deeply "unjust" to Germany, a Carthaginian Peace , as described by the economist J M Keynes and that it would be morally wrong for Britain to go to war to uphold the "unjust" Treaty. The British War Secretary Alfred Duff Cooper told the German Ambassador Leopold von Hoesch on 8 March: "through the British people were prepared to fight for France in the event of a German incursion into French territory, they would not resort to arms on account of the recent occupation of the Rhineland.

During Kristallnacht in 1938, the old synagogue in Worms was burned down twice. A further 170 Worms Jews emigrated between 1938 and 1939. An acquaintance of the family remembers that Mrs. Stefanie Baruch was in Worms around the time of Kristallnacht and witnessed the devastation of her apartment and was temporarily detained Presumably, the final police deregistration of the family took place afterwards. Ernest Theodor’s last living uncle left Worms for France and in 1941, he and his wife obtained visa from the US Consulate in Nice and made the journey across neutral Spain to Portugal. They left Lisbon , Portugal on the SS Exeter. In 1941, the whole Baruch family were stripped of its German citizenship.

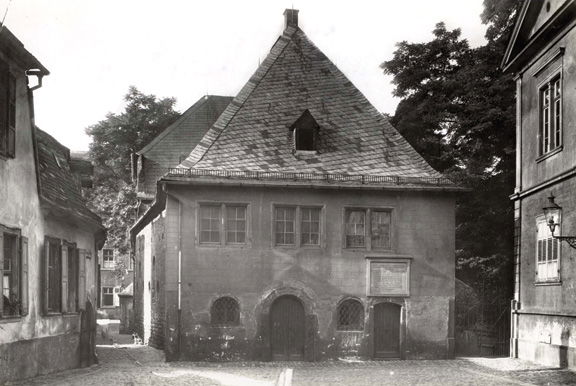

Old Synagogue- Worms destroyed during Kristallnacht

Ernest Theodor never re-joined his family in Portugal He remained in England in Manchester. In 1939, he was as living at 17 Gatley Avenue, Fallowfield Manchester. He is listed as having the normal occupation of student but was at the time working as a carpenter for the Smart Outfitting company in Market Street , Manchester. . Possibly he attended the nearby Manchester University. He was interned by the British in 1939 and then released, there is apparently no record of him being detained in the subsequent round-up of “aliens” in June 1940. .Ernest Theodore later joined the British Army and served with the 7th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment as a Private under the name of Ernest Theodor Barlow (13053490.). It is possible that like most “aliens” he served in the Pioneer Corps before joining a regular British Regiment. He had to change his name; the consequences of a a Jewish German being caught in British uniform would have almost certainly end in death.

On 22th June 1944, 7th Hampshire landed on the Normandy beaches near le Hamel. Initially they were held in reserve, but on 10th July they were given the task of capturing and holding the village of Maltot and the woods beyond. This entailed a long advance down a slope with little cover and in full view of the enemy.7th Hampshire attacked at 8.15am supported by tanks. Advancing towards Maltot, they met fierce opposition and sustained heavy casualties. Part of the Battalion did manage to enter the village where they attempted to secure defensive positions. Unfortunately, they ran into a very strongly defended enemy position with Tiger tanks concealed and dug in on the outskirts of the village. Consequently, the enemy were able to counterattack strongly and the situation for the companies in the village became hopeless. Although help came from reinforcements, they eventually had to withdraw. The casualties suffered were high, 18 officers and 208 Other Ranks were killed, wounded or missing. The 7th Hampshire continued in the line in Normandy and towards the end of July were part of the breakout from the peninsula. On 30th July their attack began on the village of Cahagnes, in the difficult close wooded country of the bocage. A night advance to capture the enemy position was unsuccessful but constant pressure was maintained and the enemy withdrew. Their next task was a deceptive frontal attack on Mont Pincon. This dominated a large area and it was essential that this feature was taken. The attack stared and the first objectives were taken without much difficulty. When phase two started, the enemy, now fully alert, inflicted many casualties and an effort had to be made to by-pass this opposition by crossing a stream in order to reach the final objective. Despite this, 7th Hampshire’s operation was successful and fulfilled its task of engaging the enemy’s attention. They had advanced to the foot of Mont Pincon and in the next few days took up the defence of the reverse slopes. On 14th August they moved forward for a successful assault on St-Denis-de-Mere. The Regiment was now part of the historic break out through the ruins of the defeated German Army. They moved to a position at Chambois through the confusion and devastation. After two further moves they crossed the River Seine on 27th August and took up a defensive position on the other side. Here they were ordered to capture the village of Tilly. This was taken despite opposition from pockets of enemy in the woods with the help of tanks. The battalion remained there for 11 days until selected to go to Brussels for garrison duty. Here they were involved with escorting prisoners, providing guards and clearing areas of suspected enemy.

They were then engaged in Operation Market Garden to relieve the beleaguered 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem. On 17 September, , the 43rd Wessex Division concentrated at Deist to form the Garden part of Operation Market Garden, , the Division was to accompany the Guards Armoured Division to carry out river crossing and protecting the corridor up to Arnhem. On 20 September they received orders to move up. The 7th Hampshires crossed the Dutch border on 20 September and had reached Eindhoven by 10am , where they were delayed as the Guards Armoured Division encountered heavy opposition further up the road. At 1300 they got moving again , being received enthusiastically as they passed through the Dutch towns of Sint Oedenrode, Veghel and finally Grave where they spent the night. They had covered 63 miles in a day.

On 21 September, they reached the outskirts of Nijmegen. , where they had cleared the area south of the railway by 10,15 and were then set to guarding the bridges. On 23 September, the news came through that the Germans had captured the parachute brigade at Arnhem, the Hampshires were order to advance to the south Bank of the Rhine at Driel and to hold a stretch of road on the south bank the Drielse Dijk, to facilitate the retreat of the remnants of the Parachute brigade. On the night of 24 September, 2600 men mainly from the Parachute brigade were able to cross to the south bank.

The Rhine at Driel (c) Gea Grevnik

The battalion maintained their positions along the South bank until the end of September, being shelled , mortared and sniped at by the Germans on the north bank of the river. The British positions on the south bank were dominated by the Korervaar brickworks. The brickworks had been there since the 1880s, built and rebuilt and modernised until the site covered 7 acres with kilns, warehouses, and the owner’s house. The Germans had halted brick production there and sent the workers home.

Looking across to the Korevaar Brickworks (c) Gea Grevnik

Map of Driel including the brickworks from Philip Reinders' book

On 1 October, the Germans attempted to force a crossing of the Rhine and despite determined British position, managed to get across and establish a bridge head at the Korervaar brickworks. The were joined by further men who crossed during the night of 2 October. The Hampshires assaulted the factory several times being driven back by poor visibility caused by mists coming off the Rhine and string German resistance. It was during an attack on the brickworks on 3 October that Ernest Barlow was killed. The circumstances are not fully known , but his body was found there. He was subsequently buried in a temporary graveyard at Molenhook

Memorial to 7th Hampshires (c) Gea Grevnik

Some 40 British soldiers were killed or subsequently died of wounds from the action on the Drielse Dijk, , a further 120 were wounded. Born near the Rhine as Ernest Theodore Baruch, he died by the Rhine in the British Amy under the name of Ernest Theodore Barlow

Memorial to 7th Hampshires (c) Gea Grevnik

Great appreciation and thanks to Gea Grevnik and Peter van der Gulden for going out to take the photos in Driel and also for consulting a copy of Philip Reinders book at the Arnhem Public Library

Sources:

Philip Reinders " 7th Battalion- The Hampshire Regiment and the fight for the Korevaar Brickworks"

As usual any mistakes are my own. If anybody has any further knowledge regarding Ernest Barlow/ Ernest Baruch. I should be happy to update the article