Lost British Graves in San Sebastian

While holidaying in San Sebastian, we walked up to the Castle on monte Urgull. I was intrigued to see signs for the Cementerio de los Ingleses. At first I thought the graves might have been from the Peninsular Wars, but they turn out to have be later and are for British and Irish casualties from the First Carlist War. The cemetery is badly preserved and most of the stones are covered in moss, the mountain has reclaimed the dead. It is a sobering thought that as you walk around Monte Urgull, some three hundred men fro, the British Isles are buried below., If you visit the nearby San Telmo museum many of the dead suffered and died in the halls and corridors of that building. So this article combines some of the common themes from this blog- British graves in foreign parts, Army Medical services and some little known history.

Overgrown memorial in the Cementerio de los Ingleses, San Sebastian

The British and San Sebastian in the Peninsular War

The First Carlist War was not the first time that British soldiers had been in San Sebastian. The siege of San Sebastián (7 July – 8 September 1813), was a notable part of the Peninsular War which quite literally changed the town forever. , Allied forces under the command of Arthur Wellesley, Marquess of Wellington failed to capture the city in the first siege. However in a second siege directed by Thomas Graham they captured the city from its French garrison under Louis Emmanuel Rey. During the final assault, the British and Portuguese troops rampaged through the town and razed it to the ground

Early 19th Century San Sebastián (Donostia in Basque), had around 9,000 inhabitants and was more liberal than the surrounding conservative province of Gipuzkoa, with both French and Spanish influences. After Napoleon's takeover in France, his elder brother Joseph I was proclaimed king of Spain in 1808. The supposedly pro- French ,Francisco Amorós was then appointed chief magistrate of the town. Although the new authorities and aides were not held in especially high regard by the population, peace prevailed throughout the period up to 1813, and French troops were generally well accepted.

All this changed , following the French defeat at Vitoria on 21 June 1813, when retreating troops under Emmanuel Rey's command arrived in the city. Wellington's army advanced into the western Pyrenees to take the mountain passes and to face Marshal Soult's army which had retreated back to France to reorganise. To evict the last French forces from Spain, Wellington needed to take Pamplona and San Sebastián. Lacking the men to attack both simultaneously, Pamplona was blockaded and San Sebastián was put under siege. Pamplona surrendered on 31 October 1813. The French were in a better position at San Sebastián, where they could be resupplied by sea. The southern part of the city's fortifications was very strong with a large hornwork blocking the approaches and with the higher town walls mounting guns that could fire over the hornwork to protect it. On its eastern side, the city was protected by the estuary of the Urumea River. British engineers detected a weak point near the riverfront at the city's southeastern corner. Assaults were possible across the river bed at low tide from both the south and the east. Breaching batteries could be placed south of the city and in sandhills on the east side of the estuary, which could themselves be protected from counterattack by the river. However British sea power could not be utilized because the Biscayan blockading fleet was understrength and French vessels regularly brought in supplies and reinforcements, while taking out wounded and sick soldiers.

San Sebastian, The mouth of the River Urumea from Monte Urgull- considerably different from 1813

Unable starve out the city, Wellington had to breach the walls and take the city by assault. The first objective was the capture of a convent of San Bartolomeo on high ground, south of the hornwork. Wellington’s army started work on two batteries 200 yards (180 m) from the convent, which were ready by 13/14 July and after continuous bombardment the convent was reduced to ruins, and stormed and captured without difficulty. On 13 July work also began on three batteries in sand dunes and a fourth on the hill of Mount Olia, all east of the river, at a range of 600 yards and 1,300 yards , connected by trenches. Daily firing until by 23 July three breaches had been made. The captured convent was engineered to protect it from the north and batteries constructed to fire on the hornwork and town. An attack was launched at dawn on 25 July. preceded by the explosion of the mine in a drainage culvert. The mine exploded too early, the troops attacked but could not get support from the artillery as it was too dark to see. Although the hornwork was assaulted , the follow-up troops were late arriving and the advance party were beaten back. The troops assaulting the walls were exposed to fire for 300 yards across the tidal flats. Although they reached the top of the breaches, they were beaten back with great loss of life,the British suffering 693 killed and wounded and 316 captured, while Rey's garrison lost 58 killed and 258 wounded. The assault having failed, the siege was reconsidered. Supplies of ammunition for the guns were running low, and on the 25 July, the siege was postponed pending receipt of more supplies by ship, and Graham was ordered to remove his guns to ships at the nearby port of Pasaia.

After driving Soult back across the frontier, Wellington waited until the rest of the battering train and sufficient supplies of shot had arrived from England before having another go at San Sebastián. Although the French had received some further drafts from blockade running vessels they only had 2,700 effective troops with 300 wounded in hospital. By 26 August the British had established batteries for 63 pieces of artillery, which blasted away at the town , destroying towers and making more breaches in the walls. On 27 August, 200 men from the British ships Beagle, Challenger, Constant, and Surveillante rowed into the bay to the west and after a brief fight and a handful of casualties, captured a small island, Santa Clara. The British then moved six guns from Surveillante on to the island to establish a battery to enfilade the town and the castle. The main breach in the east wall was almost 500 feet (150 m) long with the towers at each end demolished. In the south a sap had been pushed forward to the glacis of the hornwork.

The island of Santa Clara with monte Urgull in the background

On 31 August, another mine was exploded, which partly took down a wall, but also created a series of craters so that when the 5th Division made the assault from the south on the main breach they had some cover, but then the French opened a terrific fire. Again and again the men of the 5th Division rushed up the rubble-strewn breach, but were cut down in swathes. The French had built a inner wall that stopped the British from breaking through the defences. Hundreds of British soldiers were killed. Graham committed 750 volunteers from the 1st, 4th, and Light Divisions, but they were unable to push back the French defenders. A Portuguese brigade crossed the Urumea River and attacked the eastern breach, but also stalled. After two hours, the assault was a costly failure. After consulting with his artillery commander, Alexander Dickson, Graham chose to open fire on the inner wall, despite the risk of killing many British soldiers who were close by. As the British heavy guns first fired over their heads, the survivors of the attack began to panic. But, when the smoke cleared, they saw that the big guns had wrecked most of the inner wall. They charged, reached the top of the breach, and spilled into the city.

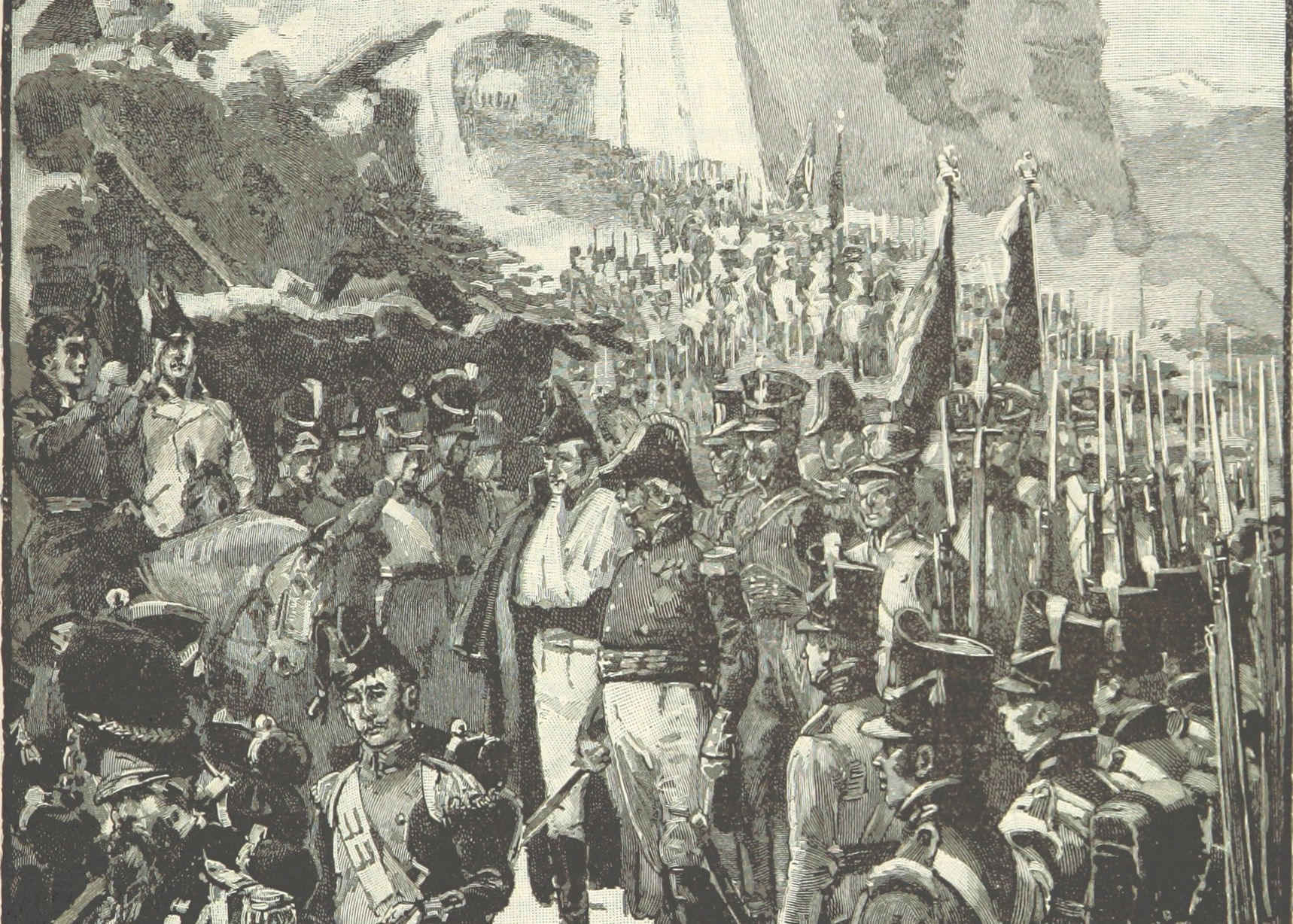

At the sight of their defence lines broken, the French retreated to the fortress on the hill of Urgull and by midday the besiegers had taken over the town. Rey and the rest of his surviving garrison held out in the Castle until they surrendered on 8 September, and, in recognition of a noble defence, the remainder of the garrison stationed in the fortress was granted the honours of war by the Anglo-Portuguese forces. They marched out of the stronghold with shouldered arms, flags flying, to the sound of the drums. Their officers were permitted to retain their swords.

The Siege of San Sebastian

On entering the town, the victorious British and Portuguese troops discovered plentiful supplies of brandy and wine in the shops and houses, drunken and enraged at the heavy losses they had suffered, the troops ran amok, sacking and burning the city while killing an unknown number of inhabitants. It appears that British officers lost control of their men, a situation which may have been worsened by the confused street fighting which followed the breach of the walls and the substantial number of officers who had been killed while encouraging the men to go through the breaches. Although British Provost Marshals tried to keep a lid on the situation by administering summary floggings the situation continued to worsen. British officers who tried to put a stop the actions of the soldiers were either ignored or threatened by the drunken soldiers; others either turned a blind eye or joined in. The city kept burning for seven days, by which time only a handful of buildings survived the inferno. The rest of the city burned to the ground including around 600 houses, except for 30 in Trinity street, *present-day 31 August,( which had been selected to host the British and Portuguese command.

Some of the bits of San Sebastian, the British did not burn

After the battle, the town council and many survivors of the destruction decided to reconstruct the town almost from scratch. Since the previous council had collaborated with the French, a new council was appointed, and a letter was written congratulating Wellington on his victory and requesting him that they be granted sums of money for those most in need. Wellington refused. The British tried to deflect the blame for the atrocity by alleging that the inhabitants of the town had collaborated with the French and helped Rey construct the defensive barricades. It may have been true that there was a substantial French community in the town and they may have assisted Rey , but is certainly does not justify what happened. It seems that Wellington had tried to discourage Graham from using rockets on the town, due to the fire risk and had warned him to keep his men under control to no avail. , Wellington later doubled down and attributed the sack of the town to the French, denying that British forces were involved in the burning of the city. In his later novel on the First Carlist war* of which more later) , G A Henty went on to perpetuate the myth, so a generation of his British schoolboy readers probably grew up thinking the French did it .

Another bit which survived the British rampage through the city

If the testimony of local people was not enough, some of the most damning accounts came from the British themselves. George Glieg who was there and witnessed the event, wrote;

“Night at last set in, though the darkness was effectually dispelled by the glare from burning houses, which one after another took fire. The morning of the 31st had risen upon St Sebastian as neat and regularly built a town as any in Spain : long before midnight it was one sheet of flame ; and by noon on the following day, little remained of it except its smoking arches. The houses being lofty, like those in the Old Town of Edinburgh, and the streets straight and narrow, the fire flew from one to another with extraordinary rapidity. At first some attempts were made to extinguish it, but these soon proved useless : and then the only matter to be considered was how, personally, to escape its violence. Many a migration was accordingly effected from house to house, till at last houses enough to shelter ail could no longer be found, and the streets became the place of rest to the majority. The spectacle which these presented was truly shocking. A strong light falling upon them from the burning houses disclosed crowds of dead, dying, and intoxicated men huddled indiscriminately together. Carpets, rich tapestry, beds, curtains, wearing apparel — everything valuable to persons in common life — were carelessly scattered about upon the bloody pavement; whilst, from the Windows above, fresh goods were continually thrown, some-times to the damage of those who stood or sat below. Here you would see a drunken fellow whirling a string of watches round his head, and then dashing them against the wall ; there another, more provident, stuffing his bosom with such smaller articles as he most prized. Next would come a party rolling a cask of wine or spirits before them, with loud acclamations, which in an instant was tapped, and, in an incredibly short space of time, emptied of its contents. Then the ceaseless hum of conversation, the occasional laugh and wild shout of intoxication, the pitiable cries or deep moans of the wounded, and the unintermitted roar of the flames, produced altogether such a concert as no man who listened to it can ever forget."

The burning of the town is remembered every year on August 31 with an extensive candlelit ceremony.

A monument to the destruction wrought by the British in San Sebastian

Of Rey's original garrison of around three thousand 850 were killed, 670 had been captured on 31 August and 1,860 surrendered, of whom 480 were sick and wounded. The Allied forces lost 3,770 killed, wounded and missing.

The French surrender with the honour of Arms at San Sebastian

The British Auxiliary Legion in San Sebastián

San Sebastián had just over twenty years to recover from war before in the 1830s, it became caught up in the Carlist Wars. There were several Carlist Wars and it all gets a bit complicated, but simply put the First Carlist War was fought between two factions over the succession to the Spanish throne: the conservative and devolutionist supporters of the late king's brother, Carlos de Borbón ( Carlos V), known as Carlists (carlistas) and the progressive and centralist supporters of the regent, Maria Christina, acting for Isabella II of Spain, the Liberals (liberales) or cristinos . It was not just a war of succession , the Carlists' goal was the return to a traditional absolute monarchy, while the Liberals sought to defend the constitutional monarchy.

María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias (1806-1878), regent of Spain during the First Carlist War

Although little known, it was the largest and most deadly civil war in nineteenth-century Europe responsible for the deaths of 5% of the 1833 Spanish population—with military casualties alone amounting to half this number. The war was mostly fought in the Southern Basque Country, Maestrazgo, and Catalonia and characterized by endless raids and reprisals against both armies and civilians. It may also be considered a precursor to the idea of the two Spains that would surface during the Spanish Civil War a century later. The liberals had the support of the United Kingdom, France and Portugal, support that was shown in the important loans to Cristina's treasury and the military help provided. After Waterloo, the British were trying to stay out of wars on the European mainland and there was little direct involvement. In order to allow the Spanish to recruit British mercenaries, the British government suspended the Overseas Enlistment Act of 1819 ( An Act to Prevent the Enlisting or Engagement of His Majesty’s Subjects to Serve in Foreign Service, and the Fitting out or Equipping, in his Majesty’s Dominions, Vessels for Warlike Purposes Without His Majesty’s License). Although the act had proved next to useless in stopping Britons fight with the Bolivarian forces in South America or the Miguelite war in Portugal, they suspended it anyway.

By 1835 the war was not going well for the Liberal side, with most of the Basque Country occupied by the Carlists and they asked their British and French allies to become more involved in the war. The French sent their Foreign Legion ,the British refused to send troops directly but in June 1835, decided to form a "military volunteer corps", the British Auxiliary Legion which became designated an auxiliary to the Spanish Legion, funded and paid for by the Spanish Crown.

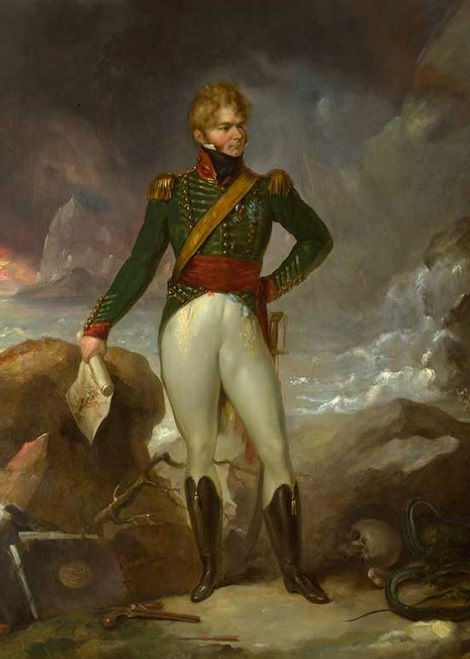

San Sebastian began to receive the British forces. The first contingent left Portsmouth on 2 July 1835, arriving in San Sebastian on 11 July.The British Auxiliary Legion was commanded by General General Sir George de Lacy Evans. Evans was from County Limerick. Educated at Woolwich Academy he joined the East India Company's forces in 1800 before volunteering for the British Army in India in 1806. With the 3rd Light Dragoons he took part in the Peninsular War as a stgff officer and them the expedition to the United States of 1814 during the War of 1812 . Returning to the European war, Evans was present at the the battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815. He went on half pay in 1818. He later became Member of Parliament firstly for Rye and from 1831 for Westminster. For a while he seems to have fairly effective reforming MP, supporting Catholic emancipation, the Reform bill, the abolition of Colonial slavery, reduction of factory hours for children , reform of the Army purchase system and the abolition of peacetime flogging in the army. Anyway in 1836, he temporarily left his constituents in Westminster to head for Spain.

George de Lacy Evans who commanded the British auxiliary Legion in Spain

General Lacy arrived in Spain on 17 August, by which time there were already 1,819 British in Santander and 2,803 in San Sebastian . The men needed time to train and educate themselves, but they did not have it. The British force was fortunately accompanied by its own medical service, prominent among who was Rutherford Alcock. Alcock obtained the MRCS diploma in 1831. During the following year he volunteered for service as a medical officer in the British Marine Brigade, which fought during the Miguelite War in Portugal from 1832 to 1834. He transferred to the British Auxiliary Legion of Spain in May 1835. Alcock published his “Notes on the Medical History and Statistics of the British Legion of Spain”, which gives not only an excellent background to condition of the troops and the privations they suffered and to their casualty rates, but also to the detailed descriptions of the surgical operations he performed.

The Legion consisted of two Regiments of cavalry . The 1st Reina Isabel Lancers (English) and the 2nd Queen's Own Irish Lancers . The Infantry consisted of ten battalions organized into "English", "Scottish" and "Irish" brigades. All foot units were single battalion regiments with six battalion/centre companies, one Light company, and one Grenadier company. They consisted : 1st English Battalion, 2nd English Battalion, 3rd Westminster Grenadiers, 4th Queen's Own Fusiliers , 5th Scotch – , 6th Scotch Grenadiers , 7th Irish Light Infantry , 8th Highlanders – , 9th Irish Grenadiers , 10th Munster Light Infantry , Light Infantry – The Rifle Brigade, British Auxiliary Legion. In addition there was artillery , the Corps of Sappers and Miners and a Hospital Transport Corps which were not organised on national lines.

Alexander Somerville a radical journalist had served with the Regular Army and then enlisted in the British Auxiliary Legion. gives a portrait of the types of men enlisted. The standard was no particularly high.

“Of eight hundred men, twenty were pensioners, about as many deserters, and one hundred and thirty of the whole had been in regular or militia regiments of the British service. Ninety were runaway apprentices. Weavers and cotton-spinners were the commonest professions among those from Glasgow; and bakers and printers among those from Edinburgh. Nearly a hundred had been sometime their own masters in business. Twenty-three had wives or women with them. One hundred and twenty left wives at home, the greater part of whom mentioned their having quarrelled with them before coming away. Upwards of twenty spoke of having been disappointed in love, and had left home under its influence. Ninety were known to have been transgressors of the law, by profession; the half of these to have lived without doing any thing else, but differed in the degrees of criminality, from poachers to housebreakers; thirteen of them were suspected of crimes recently committed, and for which the law would have punished them had they not escaped. Very few entered the Legion from a mere love of soldiering, and it was afterwards discovered that those who did so, manifested greater dislike to soldiering than the most of those who went recklessly into it. Almost every one gave some reason for having entered the Legion; but intoxication and the horrors following it, were generally blamed.”

For potential officers , the post war contraction of the British Army meant that even purchased commissions were difficult to come by, and even then many young and aspiring officers could not afford the price. Furthermore, numbers of experienced officers from the Napoleonic Wars were reduced to “half pay “ and probably looking for some opportunity. Apart from those who were in it for the money , some might have joined the Legion out of a sense of adventure or even some misplaced idealism, As Arthur Hallett, the protagonist of GA Henty’s novel puts it;

“I don't know much about the rights and wrongs of this quarrel in Spain, but I suppose that, as the Legion is supported by the government, I am on the right side. At any rate, the little queen is a child, and there is more satisfaction in fighting for her than there would be for a king.”

Many of the enlisted men probably could not have cared less about the "little queen" they were in it for the cash. Although Britain was slowly recovering from the post Waterloo economic depression, the country was in fairly dire straits. In the early 1830s , Southern England was in in the grip of the so-called “swing riots” – the widespread destruction of threshing machines. The reasons for the Swing riots were many and varied, but the effects of enclosure and the gradual impoverishment of agricultural labourers played a part . Between 1770 and 1830, about 6 million acres (of common land were enclosed. The common land had been used for centuries by the poor of the countryside to graze their animals and grow their own produce. The land was now divided up among the large local landowners, leaving the landless farmworkers solely dependent upon working for their richer neighbours for a cash wage. The return of peace in 1815 resulted in plummeting grain prices and an oversupply of labour. Before enclosure, the cottager was a labourer with land; after enclosure, he was a labourer without land. Workers were hired on stricter cash-only contracts, which ran for increasingly shorter periods, even for as little as a week. By the 1830s farmworkers retained very little of their former status except the right to parish relief, under the Old Poor Law system. Additionally, there was an influx of Irish farm labourers in 1829, who had come to seek agricultural work which contributed to reduced employment opportunities for other farming communities. Surplus peasant labour moved into the towns to become industrial workers. Against that backdrop , it is not surprising that desperation might have led some men to seek a mercenary service. Certainly the recruiting agents for the Spanish were not to bothered about who they recruited. Alcock notes the particularly poor quality of the recruits:

“ an average 100 men in each regiment of infantry were either too young or too old for service, deformed, diseased, or crippled. Between 200 and 300 were invalided, as men absolutely and totally incapable of bearing arms. There were not means, it seemed, of embarking all, and the greater part even of these last, were still kept hanging on with the Legion. The system of recruiting adopted by the Spanish government, paying recruiting agents so much per head, without the previous precaution of responsible examination by medical officers, led to this evil, which was soon found to be of great magnitude.”

In the summer and autumn of 1835, the recruits for the Legion were landed, at Santander, Bilbao and San Sebastian and by the end of October, between 7,000 and 8,000 men were in the country, aound 3,200 English , 2,800 Irish and 1,800 Scottish. Somerville notes that;

"The English were upon the whole a bad class as to physical capacity; a great number of them were sickly Londoners, or men recruited from Liverpool and Bristol, accustomed to the enervating life of a large city, and exposed to a total change of climate, food, and mode of life, on their arrival in Spain. The same observation applies to the Scotch, who were chiefly from the manufacturing towns—Glasgow and its neighbourhood—probably not more than 150 from the Highlands. The change of existence from a weaver to a soldier on active service is as violent as can be conceived. ‘The Irish were undoubtedly of all the Legion the men who were physically and morally the best adapted for the service. Although many were recruited in Dublin and Cork, yet the majority were accustomed to pass their days in the open fields, and to sleep soundly on a mud floor, or the hill side—to eat what they could get, and when and where, with little regularity, but with a cheerful hardihood that makes even poverty sit lightly on the heart and frame." ‘

On 30 August the Legion engaged in its first fights in the area around San Sebastian. The 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 7th Regiments were involved. This action, in which Spanish forces participated, was partly training or hardening. On 5 September, the Legion participated in the relief of Bilbao, under General Evans. His idea was to participate in minor actions to continue with the training of the troops. On 11 September, some of Evans’s new troops, under the command of the Spanish general Espartero, took part in the action in Arrigorriaga, 6 km from Bilbao, where the units were surrounded by the Carlists. Espartero, aware of the lack of training of the units, particularly the British, did not want to get involved retreated. The Legion continued to concentrate in Bilbao and by the end of October its 8,000 men, had been hardened with marches, exercises, and very low intensity encounters .

On 30 October, Evans was ordered to go to Vitoria to join the spanish forces , Evans was ordered to go directly there but aware of the capacity of the Legion, took the opposite route. A longer and more sheltered route, which would give his men the possibility of continuing their instruction. British complaints about the lack of winter equipment began. The British Legion arrived in Vitoria on 3 December 1835, and was stationed in the vicinity until April,diseases and epidemics, typhoid fever, coupled with the cold, poor housing and food conditions, lack of winter equipment plus the poor physical conditions of many legionnaires severely reduced their number. In the three months they were in Vitoria could be estimated at around 1,200 men were lost through diseases, epidemics and desertion. Conditions in Vitoria seemed truly horrific, Alcock was particularly concerned about the incidence of gangrene and the number of amputations performed. The poor physical state of the recruits sems to have left them particularly susceptible to infection.

Map of the theatre of operations in the basque Country in 1836

In early 1836, the Carlists turned against the Liberal positions on the coast and in the valleys of the Pyrenees while the Liberals reinforced their garrisons. The British Legion was used as part of the offensive launched from Vitoria and later to garrison Guipúzcoa, On 16 January 1836, the Liberals left Vitoria and its surroundings to carry out a series of offensive reconnaissance and frontal attacks, and to reach and occupy the dominant points of communication of the Plain of Alaves, while threatening Oñate, the court of the Carlist Pretender. The two key targets were the old Villarreal and the port of Arlabán . The plan was a frontal attack and the encirclement by the flanks. The force was split into three : – the experienced Spanish Espartero Division, was the main effort on the left, Spanish units and the French Legion were in the centre of the attack, and Evans and his much reduced Legion, plus Spanish units formed the right flank. Advancing on a wide front with three axes and in ad weather conditions required a great deal of coordination between units that did not exist. The initial actions of the Legion began with a series of reconnaissance actions on the Vitoria - Salvatierra axis. On 16 January in thick fog the Legion deployed a force reached Guevara Castle. The action was simple, a bayonet charge, and the Carlists withdrew. The following day, the Sierra de Arlabán was reached, the line of maximum advance, where the regiments endured another terrible night without winter equipment. Attrition was heavy, and on the 18th retreat was ordered. The Legion, in particular its infantry, after 8 months of harsh existence and the casualties suffered, mostly from typhoid and desertion, needed to reorganise. The English and Scottish regiments had suffered the most casualties, The new structure consisted of three brigades with three regiments. The first was a Line Brigade with the 1st and 4th English Regiments and the 8th Scottish The second, Light Brigade was formed by the Rifle Corps and two Grenadier Regiments, the 3rd English and the 6th Scottish. The third was made up of the 7th 9th and 10th all Irish, and comprised about1.800 men, making it the strongest. About half of Evans’s initial force had now been lost.

The remainder of the Legion's service - except for the 2nd Lancers, who served with Spanish field armies - was to be in and around San Sebastián, a Liberal- Cristino stronghold under siege by the Carlists. Evans was to command a Hispano-British army based in the city, which was to not only defend it (not difficult, considering the Carlists' lack of siege-guns) but also to serve as a striking force in conjunction with other Cristino units. The operational strength was 4.500 infantrymen, the 1st Lancers and supporters. From 14 March, the Royal Navy and the direct involvement of its Marines provided additional support. The maintenance of San Sebastian and the control of the coast up to the French border were essential for the Liberals.

San Sebastian around the time of the First Carlist war

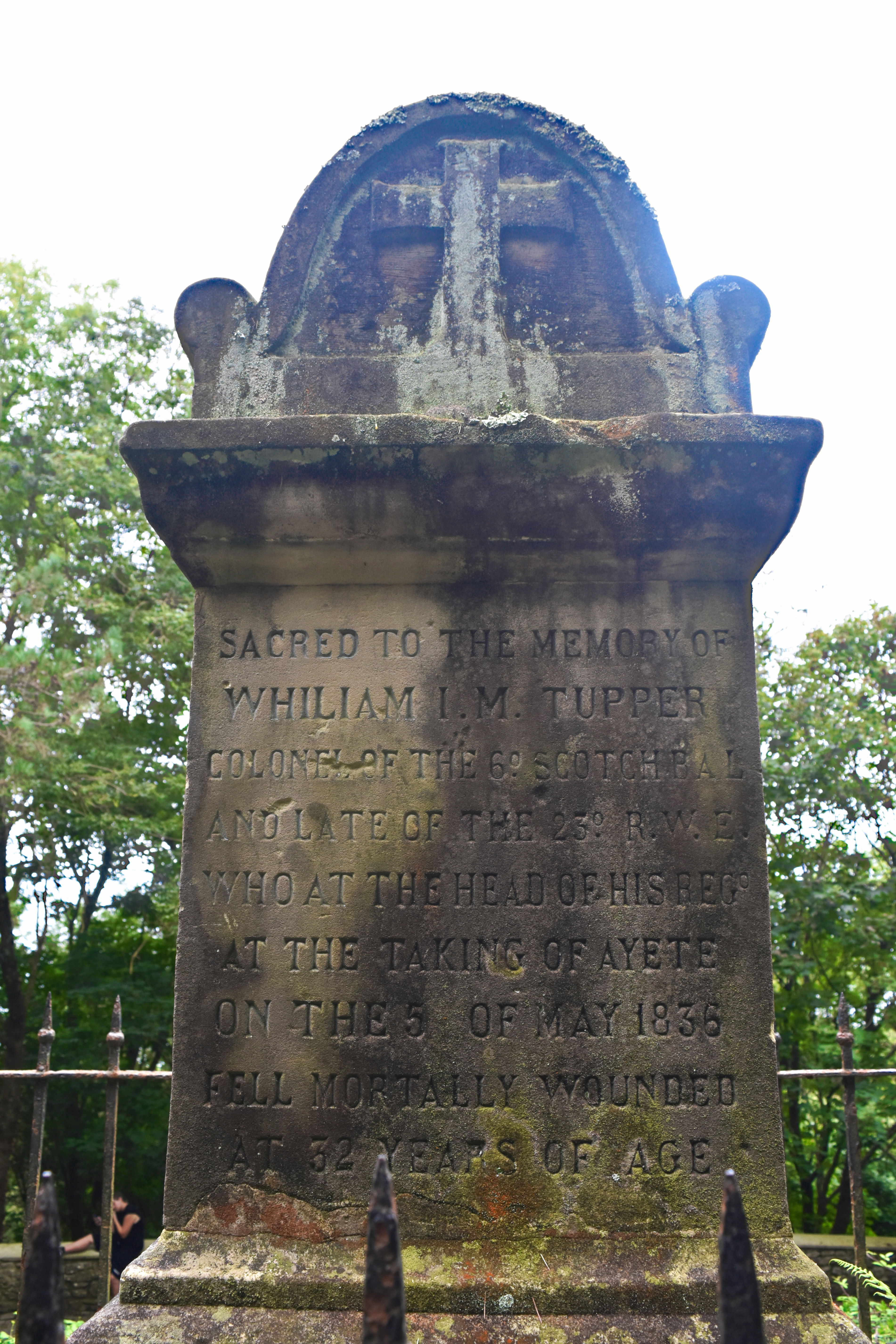

Among the British officers present in San Sebastian, William Tupper was a Lieutenant Colonel in command of the 6th Regiment of Scots of the British Auxiliary Legion. Born in 1804 on the island of Guernsey, he studied at Elisabeth College on the island. In September 1823 he purchased a commission in the 23rd Regiment ( Welsh Fusiliers), based in Gibraltar and in1826 purchased promotion to Captain. The usurpation of the Portuguese crown by the absolutist pretender Miguel, led to the intervention of a British expeditionary corps in 1827 ( the Miguelite War) in which Tupper participated with his regiment. Returning to Gibraltar in August 1828 he was caught up in a yellow fever epidemic among the ranks of the regiment. Tupper dedicated himself to personally caring for his infected men of his unit, without fear of becoming another victim. He enlisted in the Auxiliary Legion British on July 4, 1835, almost certainly with his cousin Oliver de Lancey perhaps called by the adventure, perhaps by the prospect of promotion to Lieutenant Colonel and command of one of the Scottish 6th Infantry. As soon as he arrived in the Peninsula, he was sent with his regiment to Portugalete, and on September 11, 1835 the 6th Scottish had their first baptism of fire in action of Arrigorriaga.. Then they joined the march of the Legion towards Vitoria. As noted above the lack of adequate accommodations, and a typhus epidemic decimated the Regiment. Vitoria was described as the "city of death". Lieutenant General Evans negotiated the departure of the Legion to the coast and Tupper, departed on 12 April 1836 for Santander. After only eight days his regiment was sent to help in lifting the siege of San Sebastian which was besieged by Carlist troops, and which it was feared would fall imminently. The only way into San Sebastian was by sea and embarked on the steamers "Isabel II" and "Reina Gobernadora", Tupper arrives in San Sebastián on April 23, 1836.As soon as he arrived in Donostia, he was promoted to the rank of Colonel, assuming the command of the Light Brigade, since its head, General Reid was ill. The need for a good officer in command of the unit was pressing, since a great military action was being prepared for 5 May when Spanish-British troops would try to break the land blockade attacking the Carlist trenches of the heights of Ayete.

The besieging Carlist were dug in the hills above San Sebastian . The modern resort did not exist. British ships fired on their position from La Concha Bay

Evans, impatient to regain his independence and with inadequate intelligence on the situation, launched an attack on the very day of his arrival, 5 May, without waiting for two regiments to arrive. The main effort of the Legion was carried out by the Irish Brigade, with its three Regiments, 7th, 9th and 10th, which attacked with bayonets, reaching the first two defensive lines and being repulsed at the third. They were supported by naval fire that opened up gaps, and by the arrival of the remaining units. The Carlists gave up ground until they had artillery support and halted the attack, causing the British/ Irish to lose approximately 800 men. This combat was the first victory of the Legion and the first direct intervention in ground combat by the regular forces of the United Kingdom. The Infantry and Artillery of the Royal Marines, and of the Royal Artillery and Engineers, were very professional soldiers, with great discipline and shooting training.

The British paddle steamers HMS Salamander and HMS Phoenix provide fire support to the attack on the Ayete heights from La Concha. The Carlist position is where the red flag can be seen

in the fierce battle which ensued two British war steamers, HMS Salamander and HMS Phoenix provided fire support from La Concha Bay. HMS Salamander was one of the first steam powered vessels built for the Royal Navy. She was powered by Maudslay, Son & Field steam engines her armament consisting of two Miller's 10-inch 84 hundredweight (cwt) muzzle-loading smooth bore (MLSB) shell guns on pivot mounts and two Bloomfield's 32-pounder[ 25 cwt MLSB guns on broadside trucks. She was commissioned on 27 November 1832 at Woolwich Dockyard .From 16 August 1836 to 1840 she was stationed off the north coast of Spain under Commander Sydney Dacres. HMS Phoenix was commissioned on 6 November 1833. From 9 September 1835 to June 1838 she was also off the coast of Spain commanded by Commander William Honyman Henderson, Phoenix was also engined by Maudslay, Sons and Field with a two-cylinder side lever steam engine developing 220 nominal horsepower and armed with a single 10-inch (84cwt) pivot-mounted gun, an 8-inch (52cwt) pivot-mounted gun and four 32-pounder (17cwt) carronades. The crew on each ship would have been around 135 men.

Alex Somerville, who was present at the attack and described the action in detail.

"It was a dark morning, and the showers of rain tended to keep the roads and fields in a disadvantageous state for the attack; and the men have since told me, that the dreariness looked so like the Vittoria mornings, when we marched out through the gloomy gates, so often expecting to fight, that they, from the similarity of the scene, could not fancy it more than a Vittoria excursion. "Close up, cover your files, and be perfectly silent," were orders given by officers of companies. At three o'clock the whole were moving out of the gates. The Light Brigade, under General Reid, consisting of the Rifles, 3d, 6th, and Chapelgorris, took the right of the enemy's lines, towards the river Urumea. The Irish Brigade, consisting of the 7th, 9th, and 10th, under General Shaw, took the centre; and General Chichester's Brigade, consisting that morning of the 1st regiment of the Legion, two companies of the 8th, and about eight hundred Spaniards, (the 4th, and remainder of the 8th, belonging to this Brigade, not being yet landed), took the left of the enemy's line. The convent St. Bartolome was the point to which the different brigades marched, by the main road, previous to taking each their right, left, and forward directions. Some houses, two hundred yards in front of that, were the outposts of the Carlists, and the space between was neutral ground."

The Rifles, and the 3d and 6th, were getting their complete share at the same time. When the 7th had carried the wind-mill houses in the centre, the Light Brigade succeeded in establishing themselves, and driving the enemy from other posts of a similar description. About this time, Colonel Tupper, gallantly charging with his regiment, was shot through the arm; but lest his officers and men might be discouraged, he drew his cloak round about him, to hide it, and led on his regiment for two hours longer, when, almost exhausted by the loss of blood, and as he was again fronting a heavy fire, was shot in the head. He lived a short while, and could say little more than, "tell the regiment that I can no longer command them, but that they are fit to be commanded by any one that will fight with them, and that they will receive their reward in the well-deserved approbation of their country"

At Ayete Colonel Tupper received his last and fatal wound. A rifle volley hit him in the head, almost at the end of the fighting. Major Malcolm Ross immediately came to his aid, asking for water, and said that "it was nothing" and that "could go on in a few minutes," but faded away almost immediately. He was transferred in serious condition to San Sebastian, it is almost certain that it was cared for in the military hospital at San Telmo. When they examined his body they discovered that he had two contusions, one on the shoulder and the other on the side, and that his schakó was pierced by a projectile. He was in constant pain, though he occasionally suffered severe pain, especially from the contusion on his side, and spoke of his impending death with the greatest composure and fortitude. Tupper died of his wounds on May 13, 1835 at two o'clock in the afternoon. After his death, an autopsy was performed, and the surgeons discovered a fragment of shrapnel of the size of the of a pea inside the brain, inserted half an inch, which also caused a fracture of the skull The entire medical team was surprised that he survived with these wounds for no less than eight days.

The final resting place of Lt Colonel Tupper

According to Somerville , the battle cost the Legion highly, five captains, five lieutenants, five sergeants, and one hundred and sixteen rank and file were killed. Two brigadier-generals, three colonels, two lieutenant colonels, nine majors, twenty captains, twenty-two lieutenants, seven ensigns, thirty-three sergeants, five hundred and ninety-four rank and file were wounded. Total casualties were eight hundred and twenty-three; seventy-five of them officers.

In addition to Colonel Tupper, Major Mitchell, and some other officers, died soon after the engagement. other men, returned as wounded, died; even so long after the engagement as November, Major Mitchell and Colonel Tupper were buried high among the rocks, on which stands the Castle of San Sebastian in the rocky graveyard below Monte Urull , Colonel Tupper's is the only grave monument which is still legible today.

The inscription on Tupper's grave - the only one still legible today

Although Rutherford Alcock arrived in San Sebastian on 5th May with the rest of the BAL, he had suffered a knee wound, which left him lame and unable to set up the hospital. He managed to open the surgical hospital in the convent of San Telmo by the 14th May. In the meantime the wounded were crowded into churches and temporary buildings, where classification of wounds was difficult and the facilities for operations very limited. The women of San Sebastian furnished the medical staff with bedding, linen, and everything required and helped with the wounded. Somerville described the scene>

“When the action of the 5th was fairly over-the dead who fell in the field buried-the mortally wounded, one by one finding relief in death-the daily work of amputating limbs, extracting balls, surgeons probing patients groaning-Spanish women kindly soothing them administering a cordial to one, and silently saying a prayer over the death-bed of another.”

*

The convent of San Telmo - now a museum

The convent of San Telmo consisted of two wings, at right angles, raised upon a broad terrace, some twenty feet above the court below, in which the kitchen offices, were situated. Part of the ground or terrace floor was occupied by the stores, Inspector general’s office, etc.; and the first floor, and part of the base, were formed into wards. The three higher floors of the main wing were devoted to gun-shot wounds with the second and third wards, reserved for severe and important cases were placed. The wards were 157 feet long thirty- two feet six inches wide, and fourteen feet seven inches in height. . Two small rooms were partitioned off at one end, for the ward-master, and medical officer in charge. Each ward was designed for one hundred patients; although after a battle this could rise to 800 patients for a time

The cloisters at San Telmo

The sea-breeze circling round and through the building provided fresh air ; the toilets were perpendicularly over the beach, a hundred feet below to allow the dispersal of waste. The thickness of the convent walls kept the wards cool in summer and warm in winter; and with order and cleanliness being strictly enforced, the whole hospital remained free of bad odours. The establishment was provided with good quality diets , and with everything most necessary to the efficient treatment of the wounded.

The cloisters of San Telmo where the British wounded would have suffered

in all 1351 casualties passed through San Telmo . A total of 196 died. Alcock's records reflect his relative success with minor wounds, but that most men bought in with head, thorax or abdomen wounds inevitably died. The overall death rate in the hospital was around 14,7% but by taking out the minor wounds, the percentage was substantially higher. Somerville records over 600 being wounded on 5th May, while Alcock records 382 admitted to hospital, Some of the less seriously wounded may not have required hospital treatment, and also due to his injury Alcock started keeping records several days after the event

| Type of Wound | Number | Died | Invalided | Percentage Died |

| Gunshot wounds to the head with lesions | 18 | 18 | 100% | |

| Gunshot wounds to the head without lesions | 10 | 4 | 1 | 40% |

| Abrasions of pericranium | 3 | 1 | 33% | |

| Scalp wounds | 58 | 1 | 2 | 1,7% |

| Penetrating GSW of Thorax | 38 | 29 | 7 | 77% |

| Penetrating GSW of abdomen | 19 | 18 | 1 | 95% |

| Penetrating GSW of Thorax and abdomen | 3 | 3 | 100% | |

| Penetrating wounds of joints | 37 | 21 | 11 | 57% |

| Amputations in the field | 15 | 5 | 8 | 33,33% |

| Spinal wounds | 2 | 2 | 100% | |

| Gunshot Fractures of femur | 20 | 12 | 5 | 60% |

| GSF Leg | 57 | 20 | 29 | 35% |

| GSF arm | 31 | 11 | 18 | 35% |

| GSF Fore/ arm | 52 | 3 | 30 | 6% |

| General wounds / severe | 403 | 45 | 96 | 11% |

| General wounds / slight | 585 | 3 | 0,5% | |

| Total | 1351 | 196 | 208 | 14,5% |

Alcock and his assistants seem to have done their vey best and it certainly seems that without his skilled intervention the death rate would have been substantially higher. Most of the dead from San Telmo would have been buried close to the hospital, in any case the protestant soldiers could not be buried in the local catholic cemeteries, Presumably nobody asked to deeply about any of the Irish Catholic casualties. In later years the same pattern was repeated in Belgium, France and Italy with those who died in Casualty Clearing Stations or hospitals being buried nearby- hence the location of many CWGC cemeteries. Alcock's notes and his descriptions of the treatment of gunshot wounds and amputations would prove important in the future development of military medicine.

As mentioned above the 196 hospital casualties and unknown number of the battlefield casualties were , among the rocks of Monte Urgull, the majority without headstones. Presumably only the officers got headstones anyway and only Colonel Tupper's remains,. The rest of the graves have blended in and almost become a part of the mountain

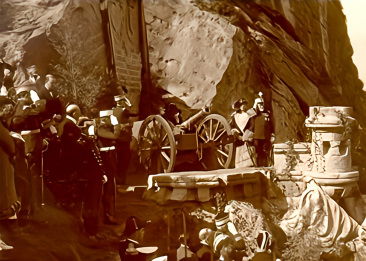

Although that is the case today, the Spanish did make an attempt to spruce up and preserve the graveyard. in 1924,a monument from outsisde the city hall in San Sebastian was moved there. The"Centenary Monument" from 1913, lwas a sculptural group representing soldiers of the war of independence while dragging a cannon, next to the wall of a wall with a sentry box.

The renovated cemetery was reopened in 19245 and Victoria Eugenia Queen of Spain, a regular holidaymaker in San sebastian unveiled a plaque written in Spanish and English, under the coats of arms of both nations, crowned by a bronze eagle, which read:

"To the memory of the brave British soldiers who gave their lives for the greatness of their country and for the independence and freedom of Spain". In another somewhat lower inscription you can also read: "England entrusts us with her glorious remains. Our gratitude will watch over his eternal rest"

Unveiling of the monument in the Cemeterio des los ingleses in 1924

At the moment when the the inscription was revealed, the anthems of Spain and the "God Save the King" were played, while they were honored by a salute from HMS Malcolm a British destroyer anchored in the bay of La Concha. Afterwards Spanish and British troops participated in a joint military parade. Among the personalities attending the event, were Queen Victoria Eugenia, the Queen widow María Cristina, the Prince of Asturias Don Alfonso and his brother the Infante Don Jaime, the special envoy for the English government, Sir Charles Oman, and the ambassador of this country in Madrid, the Spanish ambassador in London, Mr. Merry del Val, and the ambassador of the United States of America. Sir Charles Oman, a professor at Oxford University, the official representative of the British Empire at the solemn opening of the English Cemetery, read his speech and said the following:

"British officers and soldiers who have died fighting for their country, or allied with the troops of other countries, are buried in different parts of the world. But it is certain that no British soldier has such a noble and extraordinary resting place as this cemetery on Mount Urgull."

The Centenary Monument one hundred years later in 2024