Corfu-8 September 1943 by David Roberts

I recently returned from a very pleasant week in Corfu. Full of Germans, Italians and British enjoying themselves. On 8 September 1943 , it was all rather different as a beleaguered Italian garrison on Corfu found itself under attack from their erstwhile German allies, while apart from sending a small mission to found out what was going on, the British did not a great deal. The old town of Corfu still bears the scars of German bombing, with bomb damaged buildings still unrepaired- while the two Venetian fortresses which acted both as refuges and prisons are now open to tourists.

Unrepaired bomb damage in Corfu Town from German bombing raids in September 1943

Corfu bay where the sinking of the ship “Mario Roselli” by the Allies caused the death of some 1300 Italians is now visited by Leviathan Cruise liners. The fate of the Italian troops on Corfu, remains much lesser known than the events on Cephalonia. The death toll on Cephalonia, was much higher, an estimated 65 Italian officers and 1250 died during the fighting, 189 officers and 5,000 soldiers were murdered after the fighting. The events are much better known, thanks to the book and film Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. On Corfu, at least 600 Italians died in the fighting with the Germans and around 30 Officers were subsequently murdered by the Germany.

Speaking of the massacre of surrendered Italians throughout Albania and Greece, , - Prosecuting Counsel Telford Taylor at the Nuremburg trails declared:

“The calculated slaughter of captured or surrendered Italian officers is one of the most lawless and dishonourable actions in the long history of armed combat. For these men were fully uniformed. They bore their arms openly and followed the rules and customs of war. They were led by responsible leaders who in repelling attack, were disobeying the orders of Marshall (Pietro) Badoglio, their military commander-in-chief, and the duly authorised head of their nation. They were regular soldiers entitled to respect, human consideration and chivalrous treatment”

This then is the story of the days following the September 1943 and the Battle of Corfu.

Following the Italian invasion of Greece in October 1940 and the subsequent German intervention which ensured the defeat of Greek Army, in April 1941, the Italians occupied Corfu administering it separately from the rest of the Italian occupation zone in Greece. It appeared that at the war’s end, the Italians would annex the Ionian islands, seeing themselves as a successor state to the Venetian Legacy. However, things did not actually go that way. Following the Allied invasion of Sicily, the Italians looking for a way to exit the war had been carrying on complex surrender talks with British and American officials in Portugal. Mussolini was deposed by the Fascist Grand Council Meeting on 25 July 1943 and an Armistice was finally announced on 8 September. The Italian Royal Government fled south from Rome to Brindisi, unfortunately leaving the Italian Army with no clear instructions. The Italians were then in the unfortunate position of having substantial armies outside Italy in France, Albania, and Greece – almost completely at the mercy of their former German Allies.

Under Italian occupation, Corfu was administered by an Italian Civil Commissioner with Headquarters at the former Royal Palace at Mon Repos. The role was filled by Piero Parini, a former officer of Corpo Aeronautico Militare, foreign correspondent and later director for the Fascist newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia. In 1928, he was appointed coordinator of Fascist organizations of the Italian diaspora. He later worked as the Italian ambassador in Aleppo. In 1939, he became an advisor of the prime minister of the puppet Albanian Kingdom, Shefqet Vërlaci. On 5 June 1941, Parini arrived at Corfu as the new Chief of the Political Affairs Bureau of the Ionian Islands, a political body ruling the islands.

The Palace of Mon Repos. Birthplace of HRH The Duke of Edinburgh. From here the occupying Italian Forces administered Corfu from April 1941 to September 1943.

From Mon Repos, Parini enacted a rigorous Italianization campaign. On 10 August, the Ionian Islands, except Kythira, were annexed by Italy as part of the Grande Communità del Nuovo Impero Romano (Great Community of the New Roman Empire). On 16 August, Parini replaced Corfu mayor Spyridon Kollas and severed all administrative ties between the islands and the Greek mainland and the collaborationist government in Athens. Parini ruled as de facto dictator imposing new laws or ignoring existing ones as he pleased. He encouraged the migration of Italians to the islands, expanded and legalized underground Fascist organizations, and promoted his policies through a radio station and the official newspaper Gazzetta Jonica. Pictures of the heroes of the Greek War of Independence were removed from public schools as were book chapters dealing with modern Greek history. The Italian language became a mandatory school subject and shop owners were forced to use bilingual signs. On 25 March 1942, the circulation of the Greek drachma was outlawed and replaced by the Italian Ionian drachma. Greek stamps were replaced in a similar manner. During the Great Famine of 1941–42, Parini refused to allow the Red Cross to distribute aid in the region. Parini departed Corfu in late August 1943 on the yacht Aspasia, while a second ship carried 40 crates of looted art he had stolen.

On 8 September, there were around 4.000 Italian soldiers on Corfu. Most of them were from the 18° reggimento fanteria, which formed part of the Divisione Acqui ; there was also a machine gun company, a mortar company, artillery, anti-aircraft units, engineers, signal units, medical units and a bakery together with Carabinieri and Guardia di Finanza. The Navy was represented by a flotilla of minesweepers and the Air Force by a detachment at the Garitsa airfield.

In June 1940 the "Acqui" Division had participated in the “stab in the back” against France when the Italians launched their rather inglorious invasion of the South of France, joining in the Battle of the Western Alps. After the Armistice of Villa Incisa the "Acqui" was transferred back to Veneto and in December 1940 transferred to the Greek-Albanian front, taking part in the first battles, aimed at stopping the Greek offensive towards Valona. In April, with the German intervention against Greece, the Italian forces in turn launched a final offensive retaking the Albania port of Santi Quaranta ( Sarandë in modern Albania- later renamed Porta Edda by the Italians after Mussolini’s daughter) , and then advanced into southern Epirus, occupying Igoumenitsa and Murtos. Their losses during the Greek campaign (from 20 December 1940 to 23 April 1941) totalled 481 dead, 1163 missing, 1361 wounded and 672with frost bite.

The Italian commander on Corfu was colonello Luigi Lusignani. A career soldier, he entered the Military School on 5 November 1914. Appointed second lieutenant in the infantry in May 1915, he reached the rank of lieutenant and captain in the following two years. He received a war cross for military valour and a commendation for his part in the action at San Martino del Carso (14 May 1916) during the Battle of the Altopiani "for having effectively repelled an enemy attack and manned for an entire night, with only its machine gun section, the defence of a long stretch of walkway left unguarded ". After the war he was in Tripolitania from 1925 to 1927 with the XXVI Eritrean Battalion. After attending a course at the War School in the years 1928-31, he was then assigned to the Command of the Military Division of Piacenza where, in 1933, where he was promoted to major. He returned to Libya in 1936 to command the XLVI Eritrean Battalion and later to Eritrea, in Italian East Africa. In 1938, having returned to Italy again, he was assigned to the Staff reaching the rank of colonello in January 1942.In November 1942 he was appointed commander of the 18 reggimento di fanteria of the 33rd Infantry Division "Acqui" in Corfu.

colonnello Luigi Lusignani- Italian Commander of Corfu

The 18 reggimento di fanteria consisted of around 2300 NCOs and men and 120 officers, divided into three battalions. The I battaglione under ten. col. Ugo Bestozzi, II Battaglione under magg. Carbonaro and III Battaglione under ten. col. Giuseppe Randazzo. There were 650 men from III Gruppo, 33 reggimento di artiglieria commanded by ten. col. D ‘Agata, who was second in command of the garrison. 7 batteria was commanded by cap. Gino Francato, 8 batteria by cap. Ernani Falcocchio and 9 batteria by cap. Giuseppe Vurro. There was also the 333rd anti-aircraft battery, whose 5 batteries of 20 mm guns were commanded by cap. Carlo Bonali- the individual batteries being commanded by ten. Natale Pugliese, ten. Michel Quaglio, ten. Mario Mantini, sott. Agugliaro and sott. De Leo. An engineer company of around 14 offices and 620 men, mainly involved in radio communications was commanded by ten. Bruno Zanoni. There were also around 400 men of the Guardia di Finanza based in Corfu, under the command of Capitano Bernard . The troops were mainly static units defending the vital shipping routes around Corfu. The Corfu garrison was subordinate to the Italian XXVI Army Corps under generale della Bona in Ioannina in mainland Greece, and in turn to the Italian 11th Army in Athens, commanded by generale Carlo Vecchiarelli, which following 25 July operated under a joint Italian- German Command

On 9 September 1943, the German General der Gebirgstruppe Hubert Lanz assumed command of the newly formed XXII Gebirgskorps at Epirus. The Germans feared an Allied landing in Greece and were engaged in continuous anti-partisan sweeps. Collective punishment of entire localities for guerrilla attacks was common, with directives to execute 50 to 100 hostages for each German casualty; only four days before Lanz assumed command, men of the 98 Gebirgsjaegerregiment of 1. Gebirgs-Division under Lieutenant-Colonel Josef Salminger, had executed 317 civilians in the village of Kommeno in Albania. Allegedly Lanz clashed with his subordinate, General Walter von Stettner, over the treatment of civilians, although reprisals remained a standard tactic.

General Hubert Lanz. Sentenced to 12 years imprisonment for his sanguinary activities in Greece and the Balkans. Denied that the atrocities on Cephalonia took place.

10th September

“The Italian troops of the 11th Army will adopt the following line of conduct. If the Germans do not offer armed violence, Italians will not use their arms against them, nor will they make common cause with the rebels or with any Anglo-American forces who may land. They will however, meet force with force. Every man will remain at his post and his present task. Exemplary discipline will be enforced by every possible means. The above will be communicated to the corresponding German HQ.”

Lusignani refused to obey this order and summoned a conference of his senior officers. On the morning of the 10th, Colonel Kotz commanding the small German contingent on Corfu, together with the German consul Spengelin attempted to persuade Lusignani to surrender which he refused to do.

By this time the Italian War Office had safely reached Brindisi and on 10 September that they began to issue orders to resist the Germans. On 11 September Lusignani received two telegrams from comando tattico by now at Francavilla Fontana, in Puglia, in which they ordered him: "Oppose with force any attempted German landing” and "Provide immediately for the capture of German units considering them to be prisoners of war “.

Lusignani also received a delegation of local representatives, including the Metropolitan the Orthodox church, the Prefect and the President of Court requested that the Italian release their Greek political detainees. meanwhile Papas Spiru of the Greek resistance made known that he wanted to meet the Italians. D’Agata left Corfu Town to meet him at a secret location. Spiru requested authority to attack the Germans, but the Italians asked him to wait.

Meanwhile, the Germans began to drop leaflets on the Italian garrison, promising them

“Italian Comrades! Why keep fighting ? The Badoglio Government has sold you to the British, until you and your country do something about it. Now they want to transport you to British prison camps , separating you from your families, from your wives, from your children and this in reward for your faithful custodianship of the island of Corfu- during which you have been granted no leave. The intention of the German Army is to take your place and return you safe and sound to to your homeland”

It was , of course a big lie.

11th September 1943

At the time of the armistice there were few German soldiers, around 450 men - so they were heavily outnumbered by the Italians , most of the Germans were air force men or marine pioneers based around the airport at Garitsa or the port.

On 11 September Captain Wilhelm Spindler of 54 Gebirgsjaeger-Bataillon arrived on the island from the Greek mainland to start negotiations with colonello Lusignani, , who still refused to lay down arms , not having received any orders to do so.

12th September

The next day Major Harald von Hirschfeld of 1. Gebirgs-Division, accompanied by Spindler arrived by sea for further negotiations, he was similarly unsuccessful, reporting that Lusignani was not disposed to negotiate and remained hostile to the Germans,

That evening the Italians freed all of the 500 political prisoners held in the concentration camp on Lazzaretto island in Corfu Bay. They also made good on their promise to start distributing arms and ammunition to the Greek resistance.

Lazzaretto Island in Corfu Bay-on the 12 September the Italians freed all their Greek political detainees held there.

13th September

At 7.00 von Hirschfeld returned to Corfù for the last time, accompanied by colonello Carlo Rossi from the staff of the of the Italian 26th Army Corps at Ioannina. Von Hirschfeld ordered Lusignani to surrender by 1130 that morning. Rossi gave him a signed letter from generale della Bona, telling him that Italian forces in mainland Greece had laid down their arms and inviting him to surrender and avoid further bloodshed. Apparently colonello Rossi then whispered to Lusignani, that della Bona had only signed the order under threat of death and advised him tp continue to resist. Von Hirschfeld and Rossi then returned to the mainland port of Igumenitza.

While negotiations continued a unit of the 99 Gebirgsjaegerregiment under Captain Siegfried Dodel, was already preparing for a surprise landing on Corfu at Benitza . By 12.05 news reached them of the Italian refusal to surrender but they went ahead with the attempted landing anyway. The Italian defenders, particularly the 333rd anti-aircraft battery under sott. De Leo subjected the attempted landing to heavy fire, hitting planes and landing craft.

At 18.45 the Germans returned to Igumenitza, aware that they did not yet have enough firepower to overwhelm the Italian defences. By the evening German bodies were washing up on the shores of Corfu.

Major Harald von Hirschfeld of 1. Gebirgs-Division- responsible for the massacres on Cephalonia. Fortunately for the Italians on Corfu he did not return there. Killed in action towards the end of the war, so never faced justice.

The Italians still had substantial forces in Albania. On that evening around 1000 officers and men from the 49° reggimento fanteria of the divisione Parma, commanded by colonello Bettini, together with supporting units began to disembark in Corfu from Porto Edda. Although, this was potentially a useful addition to the number of defenders on Corfu, the men from Porto Edda, were actually largely disarmed or short of ammunition and were mainly trying to get home. The precise number arriving from Porto Edda is not clear, but their sudden arrival, put further stress on the supplies of food and ammunition in Corfu, although some assisted with the coastal defences, a large number of the infantry were not involved in the subsequent defence of Corfu. By now news was reaching Corfu, that rather than being sent home, disarmed Italian units were being sent to concentration camps.

The Germans decided to suppress the large Italian force on Cephalonia, before attempting a landing on Corfu. Instead, they launched a devastating aerial bombardment of Corfu. Heinkel 111 bombers attacked the Corfu Town by night. On 14 September at midnight, the whole city of Corfu appeared to be in flames. The local fire brigade was in no position to deal with such large-scale fires, in which whole quarters were destroyed. The civilian population did their best to hideaway in the subterranean tunnels of the two Venetian forts. When they emerged in the morning, they found much of the city a smouldering ruin. The bombing destroyed Corfu’s Municipal Theatre and the Ionian university as well as countless houses and civilian targets, by day Ju-97 bombers bombed Italian positions across the island.

The civilian population took refuge in the tunnels of the Old Fortress to avoid the bombing

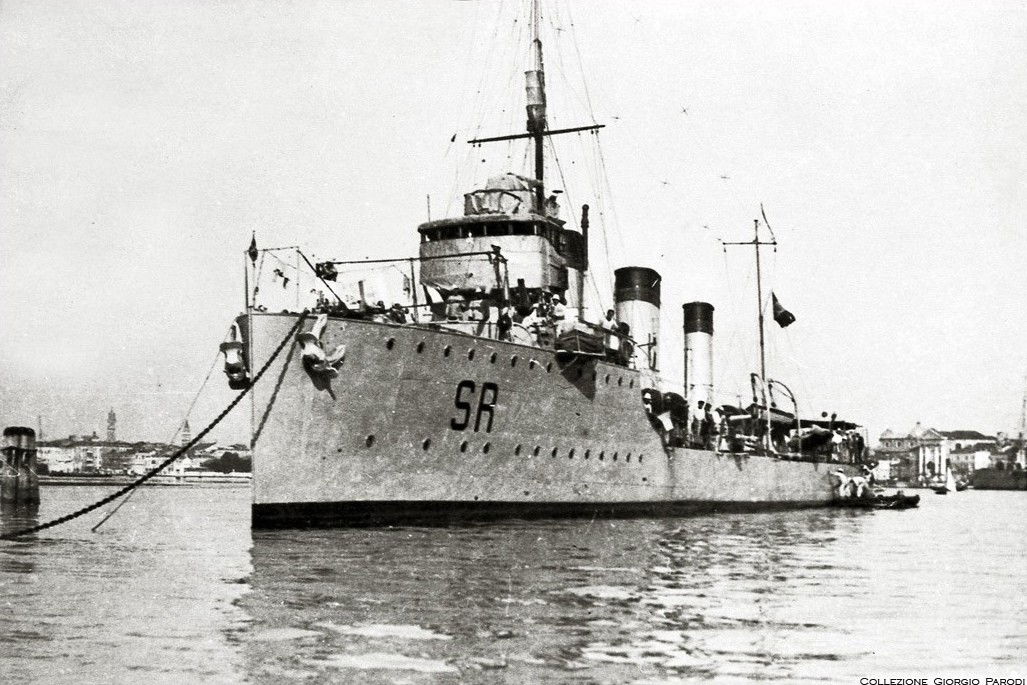

Among the Italian particularly noteworthy was the role of the Guardia di Finanza, capitano Bernard and his men were responsible for capturing and disarming the Germans in the port of Corfu, notwithstanding the intense naval bombardment at the time. Capitano Francesco Cultrona of the GdF was killed during the raid. Particularly heroic were the actions of tenente Renato Benini who during the intense bombing managed to secure a deposit of weapons at the old Venetian fort and ammunition preserving them from being engulfed by the fire. Realising that capitano Cultrona had been killed , Benini took over command and encouraged his men in their resistance, It was shortly after this raid, again on the evening of 13 September, that the Italian ships “Sirtori”and “Stocco” arrived in Corfu: their dispatch from Italy had been decided by Supermarina following a request made by the command of Corfu. , who believed that with their armament the two torpedo boats could help reinforce the modest defences of the island in anti-ship and anti-aircraft function. and Stocco were the only ships available in Brindisi at that time, so Supermarina had ordered their immediate departure. The commander of the Sirtori had fallen ill, therefore tenente Alessandro Senzi, replaced him at the last moment.

14th/15th September

At about nine in the morning while the last group of soldiers from Porto Edda was disembarking, the Luftwaffe returned with a mixed formation of Junkers Ju 87 "Stuka" dive bombers and Junkers Ju 88 medium bombers. dropping explosive and incendiary bombs in large quantities on the city and port of Corfu. The planes were flying from Araxos on the Greek mainland, some 90 minutes away.

Unrepaired bomb damage from the German attacks in September 1943. Still visible in Corfu Town today

Three of the "Stukas" - belonging to I. Gruppe/ Sturzkampfgeschwader 3 targeted the “Sirtori” and “Stocco”, at anchor in the bay, carrying out repeated swoop attacks: the “Stocco” was unscathed, but at 9.10 the “Sirtori” was hit by a salvo of six bombs and severely damaged later being deliberately run aground on the beach of Alykes Potamos, south of the Lazzaretto island , to prevent her sinking in deep waters. The air attack that put the Sirtori out of action resulted in a single victim among her crew: the 23-year-old stoker sub-chief Bartolo Boscardin,

The Italian torpedo boat Sirtori bombed and sub in the waters of Corfu Bay

The “Stocco” was ordered by Supermarina to leave Corfu and returned to Brindisi. In the afternoon of September 14, other air raids took place, Corfu was also fired on by a 150 mm battery located on the nearby coast of Epirus.

During the first bombings the headquarters of the Corfù Marine Command and the barracks that housed the detachment of sailors were both hit by bombs and rendered unusable; between 13 and 14 September, therefore, both the Command and the detachment were transferred to another location outside the city of Corfu. That evening tenente Senzi of the Sirtori, decided to use the crew of the torpedo boat for the land defence of the island;, part of the Sirtori guns, being removed to enhance the land defence. With the Germans were raining death down on Corfu, the British resorted to dropping morale boosting messages.

17th / 18thSeptember

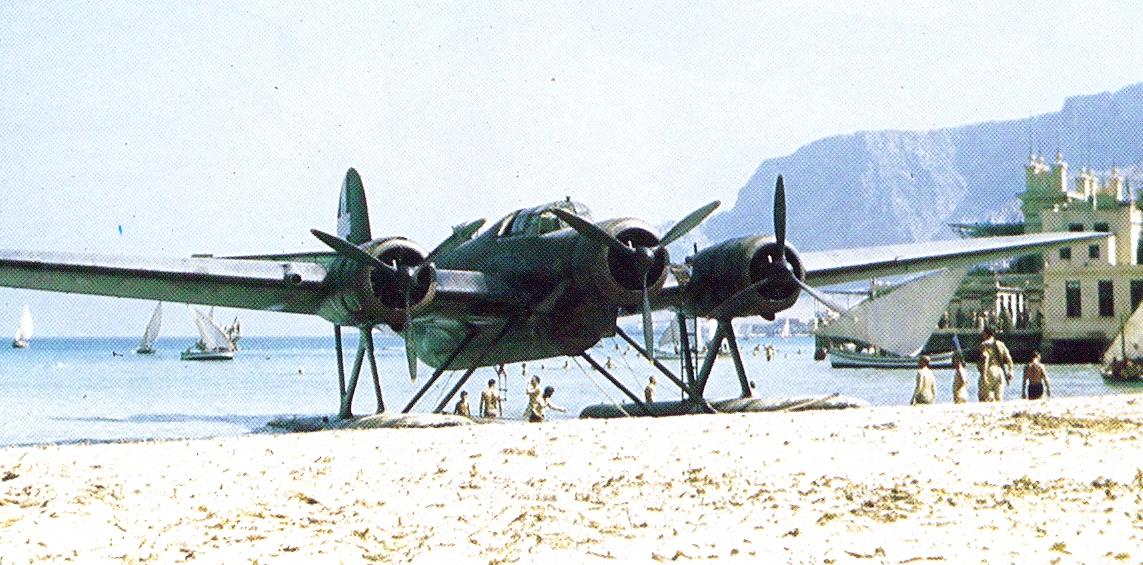

During 17th September, Corfu Town continued to burn as the Germans recommenced their bombing. At Brindisi the Allies allowed units of the Regia Aeronautica, to fly missions to Corfu. The Italians managed to evacuate the worst of the wounded using CANT Z506B seaplane back to Brindisi. The planes could only carry 14 casualties at the most, but it was better than nothing.

A CANT Z506B seaplane - they were used to fly the critically wounded out of Corfu and back to Italy

On the 18th , one of the rescue seaplanes piloted by tenente Nicolo Ainis was shot down with its load of casualties, possibly near Mathraki island they were saved by a Greek fishing boat. Ainis made it back to Brindisi and was flying again the next day. Meanwhile, he lobbied Air Commodore Foster of in charge of the air component of the Allied Military Mission in Brindisi to provide air support for the beleaguered Italians in Corfu. Foster was in Brindisi to organise the integration of the Italian Air Force with the Allies, his command authority extended no further than the Bay of Otranto, so any requests for assistance to Corfu had to go to Allied HQ in either Cairo or Algiers which ended up far too late.

The Regia Aeronautica did what it could at a cost in planes and pilots. RE2002 dive bombers of 5 Sturmo at Brindisi, which 10 days previously had been attacking the Allied landings in Calabria were now attacking German shipping off Corfu. Five dive bombers et off to attack the German, one piloted by tenente Venza was shot down in flames. On 19 three more RE 2002s flew a mission of Corfu Bay, one was shot down tenente Felice Fox being Killed in action.

A RE2002 dive bomber of the Cobelligerent Italian Air Force, which tried to give some air support to the Italians trapped in Corfu

20th /21st September

The Allies decided that they knew absolutely nothing about was happening on Corfu, so they decided to send a mission, On 21 September, Captain Oliver Churchill of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), together with his radio operator Signalman Harrison were parachuted onto the island. Churchill was a fluent Italian speaker. Born in Stockholm in 1914 the son of William Algernon Churchill, a British Consul who served in Mozambique, Amsterdam, Brazil, Stockholm, Milan, Palermo, and Algiers. Churchill was educated at Stowe School and Cambridge University where he read Modern Languages at King's College, after which he studied architecture at Cambridge before his studies were interrupted by the war. As war became imminent, Churchill joined the Territorial Army and was soon called up to the Worcestershire Regiment. He joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and In December 1941, was posted to Malta and the Middle East to train Italian partisans and was subsequently posted to SOE Middle East headquarters in Cairo from where he was involved in clandestine, behind-the-lines work in Greece and Italy. His nom de guerre was Anthony Peters .

Observers spotted their aircraft circling Churchill and Harrison were picked up by the EAM partisans who had been watching out for German parachutists, as soon as they landed and handed over to Papas Spiru who took them personally to the Italians. Although, Churchill established his credentials and that he had been sent by General Wilson in Cairo to communicate the requirements of the Italian garrison Initially the Italians seemed distrustful of the British duo. Things were not helped by the fact that the radio had been badly damaged on landing and they were unable to establish contact with Cairo. That night, the Italians sent a mission across to Sarandë which was still not yet occupied by the Germans to recover supplies of ammunition for their guns.

23rd September

While the 1. Gebirgs-Division was engaged in Cephalonia the Germans continued to plan an attack on Corfu. Lanz approved the attack plan on 22 September, ominously called Operation Verrat ( “Betrayal”).

Finally at 13.00 on 23 September the Germans started to land at Preveza in the south under the command of Hauptmann Dittmann, with a battalion of the 98 Gebirgsjaeger, a section of 79 Gebirgsartillerieregiment and a company of the 54 Gebirgs-Pionier-Bataillon.

24th September

The main German landing party reached the lagoon of Korissa, in the southwest of the island around 0.30.. Although this meant a longer voyage from mainland Greece, the lagoon with its surrounding long sandy beaches and dunes, presumably offered an easier landing site than the rock coves and inlets on the eastern side of the island. Shortly afterwards, the Italians identified the bridgehead and the Italian artillery opened fire. The German landing continued despite the Italian shelling. One by one the Italian coastal batteries fell to the Germans. By 4.00 am, the Germans had occupied the heights of Maltauna which dominated the entire area, and the Italian Units began to retreat northwards.

The Lagoon of Korissa where the Germans landed in force on Corfu

Around 5.00 the Germans began raking the central sector of the island for surviving Italian units. Some gave up without a fight but at Argyrades , a well organised group took on two companies off moving along the main road. It was a bloody conflict with no quarter given, any Italians found with their weapons were shot out of hand by the Germans. By the mid-morning nothing further was being heard from Italian garrisons in the south of the island Towards the evening the secondo battalion of 98° Gebirgsjaeger had completely achieved its objectives and held the central part of the island around 500 Italians had been killed and 1.500, taken prisoners. Those identified by the Germans as unarmed and “deserters” were not killed immediately. The only success for the Italians was in removing from Kassiopi, all of the German prisoners who had been captured on the island and sending them back to the Italian mainland.

25th September

The early success of operations allowed the Germans to make a second landing under the command of Captain Feser, comprising men of 99° Gebirgsjaeger, a section of 79° Gebirgsartillerieregiment. Disembarkation concluded at dawn.

Also arriving on the island were the HQ under Lt Colonel Remold and General Walter Stettner, commander of 1. Gebirgs-Division. Who had fought with them in Poland, Norway, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union, In the morning the two German columns commanded by Dittmann and Feser, started operations to break the Italian resistance,

The Italians had prepared a last line of defence at the Stavros pass and at the heights around Corfu Town . One by one these Italian positions were overrun and massacred by German assault troops, , as a result a number of Italian units began to hand over their weapons and surrender, while their officers retired towards Corfu Town. By mid-morning, communications with the strong point at Koritza had been lost . Lusignani decided to withdraw his tactical command I Corfu Town and take his staff some 20 km to the north to Skripero with a view to continuing resistance.

Skripero- a village in the mountains about 20km from Corfu Town where colonello Lusignani prepared his last stand

D’Agata as second in command remained in Corfu. Although Italian planes overflew the island, they provided no hep to the men on the ground. By 1430 Stavros had fallen and German armoured vehicles were seen in the area. By the middle of the afternoon, up in Skripero it was clear that the situation was hopeless, they had run out of arms and ammunition and there seemed no hope of any help arriving

Corfu Town remained well defended by a line of fortifications centred on the south of the city and supported by an efficient anti-aircraft defence. Feser was sent to prevent the Italians retreating north, meanwhile German Artillery began to target the capital. Dittmann’s group attacked the Italian defensive line which they overcame after a violent struggle. Around 16.20, the Italian Garrison in Corfu ran up the white flag over the fortress, they sent their last radio message to Brindisi at 16.20 “We have destroyed all secret documents. We are about to destroy the radio “At 17.00 the Germans entered Corfu Town.

The Old fortress in Corfu, where the Italians out of arms and ammunition surrendered on the afternoon of 25 September

At Skripero Churchill agreed with Lusignani that it was time to leave and together with Signalman Harrison made good his escape. Towards 23.00, the Germans arrived at Skripero, Lusignani was waiting for them and after brief negotiations, he agreed terms for the surrender of the Italians on the island – he insisted on the condition that the defenders be treated as Prisoners of War.

Another view of Skripero where Lusignani was left with no choice but to surrender on the evening of 25 September

By the morning of 26 September, the Germans were in control of the whole island.

27 September and after

On 27 September, colonello Lusignani, colonello Bettini, of the divisione Parma and another 19 officers were murdered. During the conflict 600 Italians had been killed either in combat or executed afterwards, a further 5000 remained as prisoners. The Germans lost around 200 men.

Having left Lusignani at Skripero, Churchill and Signalman Harrison headed for the coast at Palaiokastritsa. It took several days before they were able to arrange for an unreliable motorboat skippered by a septuagenarian to be made seaworthy Departure from Palaiokastritsa was further delayed for two days by strong winds and currents.

Palaiokastritsa from where Major Churchill of the SOE made his escape from Corfu

With a crew of three who he later described as “one dotard, one drunkard and the father of a thief” and 11 Italian soldier and sailor escapees who joined the boat, Churchill and Harrison were taken by night to the islands of Mathraki, Ereikoussa and Fanos, before making an overnight crossing of the Adriatic towards the heel of Italy. The wind changed direction during the night and blew them off course, passing to the west of the heel of Italy into the Bay of Taranto. Churchill recalled:

"By first light we saw land. But for one of the Italian sailors from Corfu, the captain would have turned about. He did not recognise the coast and thought we had sailed in a circle and were off Albania. The captain was too bleary-eyed to read the compass and the bosun helpless with the sails. All this the sailor saw to, as well as keeping the mechanic at the pumps. Our sailor saw that we were in the Bay of Taranto. The drift had carried us five hours off our course.”

They turned round and sailed around the peninsula to land at Otranto. Churchill was then taken to Brindisi where he was debriefed by Captain Teddy de Haan at the Italian SOE base at the Allied Military Mission, de Haan had arrived there on 11 September and was now running a Special Operations wireless group from the Hotel Imperio. From Brindisi, Churchill returned to Cairo. he was awarded an MC and returned to Northern Italy in 1944 to act as a liaison officer with partisans

On Cephalonia, the Germans had murdered both officers and enlisted men alike. In Corfu after the surrender, they “restrained themselves” to killing only officers. In fact, assuming that there were more than 150 officers on the island at the time the Germans attacked, they appear to have allowed the majority on Corfu to live, including all three battalion commanders of the 18 reggimento , tenn. col. D’Agata, and many junior officers of the regiment.

On Corfu the Germans appear to have pursued a selective campaign of vengeance particularly against Lusignani and the junior artillery officers who had inflicted such heavy casualties on them. Italian sources attribute the absence of a general massacre, to the fact that von Hirschfeld who was deemed principally responsible for the Cephalonia massacre did not return to Corfu. It is difficult to establish a definitive list of the number of Italian officers executed on Corfu, they include;

- Capitano Ernani Falcocchio , 22 artillery regiment

- Capitano Gino Francato

Killed after Germans entered Corfu Town

- Tenente Albano, commanding airfield

- Tenente Medico Ernest Bringali

Subsequently murdered

- Colonello Luigi Lusignani

- Capitano Carlo Ferraro, adjutant to the Colonel

- Tenente Martinelli, Operations officer of the 18th regiment

- Colonello Elio Bettini of the 49th Regiment, Parma Division

- Capitano Pietro Brera, his adjutant

- Capitano Teobaldo Caggiano- carabinieri

- Capitano Nicola Ostuni, Reggia Marina

- Capitano Carlo Bonali, 333rd Anti-aircraft battery

- Tenente Mario Mantini

- Tenente Natale Pugliese

- Tenente Michele Quaglio

- Sottotenente De Leo

- Sottotenente Agugliaro

- Tenente Bruno Zanoni

- Maggiore Aurelio Gisondi, VV artillery group

The German orders were that the Italians were to be shot secretly and that the bodies were to be disposed of on land, so they were taken out and dumped in the seas of Corfu.

For the Italians on Corfu the ordeal was far from over. Following the surrender, the Germans incarcerated the remaining Italian prisoners at Garitsa airfield and in the old fortress to await transportation off the island. The former Italian Merchant vessel, Mario Roselli- now requisitioned by the Germans and flying a German Ensign arrived in Corfu Harbour to transport the prisoners to the mainland. On 10 October, Allied planes possibly USAF P38 fighters operating from Foggia attacked the small boats ferrying the men to the Mario Roselli. The fighter bombers returned and scored a direct hit on the Mario Roselli, which sunk in the harbour. It estimated that some 1300 Italians lost their lives in this attack. Allegedly the Germans machine gunned the survivors as they swum back to shore.

The "Mario Rosselli" sank by Allied bombers in the Bay of Corfu with an estimated 1300 Italian prisoners killed

Several the Italian officers murdered on Corfu received awards for valour. Lusignani was posthumously awarded Italy’s Gold Meal for Military Valour. The citation read:

" Military Commander of the island of Corfu', faithful to military honour, he refused to be intimidated into laying down of arms and on his own initiative organised the defence of the island. For 12 days he resisted German air and land attacks, acting as an example to the men under his command of ongoing bravery finally, with every hope of relief fading, with his units decimated and without any remaining artillery, he was overcome by an enemy superior in numbers. Captured by the Germans, he met this fate”

Bettini was awarded the same medal, with a similar citation

On 18 September 1943 Vecchiarelli was arrested by the Germans together with other Italian generals. Shortly after he was transferred to the prison camp for officers Offizierslager 64Z in Schocken in which most senior Italian officers were concentrated. He remained there for just over four months, to his credit he flatly refused the offer made to him to join the army of the Republic of Salò. He was sent back to Italy, where the court of the Italian Social Republic of Brescia handed him a 10-year prison sentence for anti-German behaviour in Greece. On 25 April 1945 he was freed by the partisans of the CLN of Brescia, and joined the Fiamme Verdi partisans, participating for a few days in the war of liberation. Della Bona was also sent to Schocken where he remained until the camp was liberated by the Soviets in early 1945.

The Senior Officers of course had it fairly easy compared to the men. NCOs and other Ranks were not treated as Prisoners of War but given the status Internati Miltari Italiani ( IMI) and those who survived the crossing to the Greek Mainland were headed into cattle trucks and sent to work camps in Poland and Germany for the rest of the war. Many never returned to Italy. The more fortunate headed for the hills where they joined with Greek resistance forces.

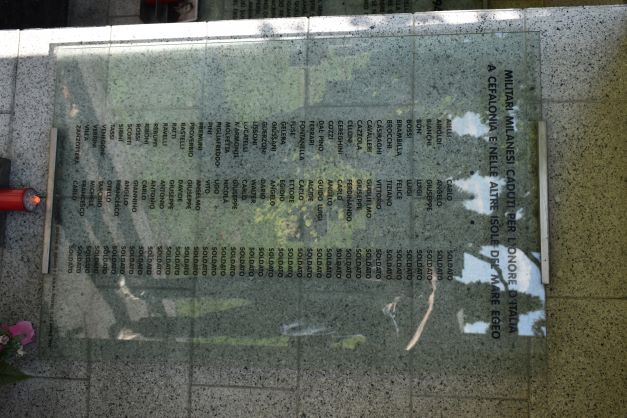

Monument in Milan's Cimiterio Maggiore, to Interned Italian soldiers who died in German work camps

Unfortunately, while they were giving out bravery awards the Italians did next to nothing to help secure convictions against any of the Germans who were responsible for the atrocities on Corfu. Von Hirschfeld and Von Stettner were both killed in action towards the end of the war and so were beyond justice. Lanz surrendered to the American Army at the end of the War. The Americans did at least bring Lanz to trail in 1947 at the so-called "Southeast Case"/ Hostages trial of the Nuremburg Tribunal, along with other Wehrmacht generals active in the Balkans. The trial was concerned with the atrocities carried out against civilians and POWs in the area. In Lanz's case, the biggest issue was the Cephalonia massacre. However, his defence team cast doubt on the allegations concerning these events, and as the Italians did not present any evidence against him, Lanz convinced the court that he had resisted Hitler's directives and that the massacre did not happen. He claimed that the report to Army Group E reporting the execution of 5,000 soldiers had been a ruse employed to deceive the Army command, to hide the fact that he had disobeyed the Führer’s orders. He added that fewer than a dozen officers were shot, and the rest of the Acqui Division was transported to Piraeus through Patras. Clearly in that version of events, 5000 men who never returned home from Cephalonia must have vanished into thin air His defence also argued that the Italians were under no orders to fight from the War Office in Brindisi and would therefore have to be regarded as mutineers or franc-tireurs who had no right to be treated as POWs under the Geneva conventions. Lanz received a 12-year sentence and was released, reaching the good old age of 86 and died of natural causes.

Since the massacre on Cephalonia was widely known and reported on in Italy after the war, it is a complete mystery ad to why the Italians were unable to offer up any evidence against Lanz. The whole issue of war crimes was touchy with the Italians, with a number of Italians potentially open to similar charges as Lanz and the other defendants, at least as far as the charges of hostage taking, reprisals etc.

Strangely ,there is no memorial to the Italian dead-on Corfu. In the years after he war, the dead-on Cephalonia were exhumed and reburied at the Italian War cemetery in Bari. A memorial was erected in Cephalonia

Monument to soldiers from Milan killed on Cephalonia and other Greek islands following the Armistice on 8 September 1943

Italian Units participating in the Battle of Corfu

Regio Esercito

1ª compagnia del VII Battaglione Carabinieri mobilitato

30ª sezione mista Carabinieri mobilitata

18° Reggimento Fanteria su tre Battaglioni

3ª compagnia del CX battaglione mitraglieri di Corpo d'Armata

33° Battaglione mortai da 81

33ª compagnia cannoni da 47/32

III Gruppo obici da 75/13 del 33° Reggimento Artiglieria

XC Gruppo Artiglieria da 105 di Corpo d'Armata

333ª batteria contraerei da 20 mm

217ª compagnia genio lavoratori

un plotone della 31ª compagnia Genio artieri

un plotone della 33ª compagnia mista Genio T.R.T.

un reparto della 44ª sezione Sanità Militare con due Ospedali da Campo (39° , 824°)

un nucleo della 5ª sezione Sussistenza con un nucleo della 9ª squadra panettieri

un nucleo della 143ª autosezione pesante

Marina Militare

Comando Marina Corfù

una squadriglia dragaggio

Areonautica Militare

Comando Aeroporto distaccamento servizi areoportuali e di idroscalo

Guardia di Finanza

Comando I Battaglione mobilitato

1ª compagnia fucilieri

3ª compagnia fucilieri

Sources

Diario della Resistanza italiana a Corfu- Ten.col. Alfredo D'Agata- Rivista Militare

Le Armi e L'Onore - Il Colonnello Luigi Lusignani e la Difesa di Corfu- Angelo Ceorizza, Bollettino Stoico Piacentino , 2001