Arrivals and Departures at Ventimiglia and Bordighera

In 1917, a British Expeditionary Force was set to Italy. The first time a British Army had fought on the Italian Peninsula. For most British soldiers their first encounter with Italy was the border town of Ventimiglia. Coming from the cold, wet battlefields of France and Flanders, Italy opened up a whole new world .Whether arriving by road or railway , Ventimiglia was the first Italian town for most British troops. For British casualties being evacuated from the front Ventimiglia was their exit point from Italy, often from hospitals in the nearby resort town of Bordighera.

This article continues a number of the themes of this blog, particularly First World War Medical services, the British in Italy in 1917 and 1918 and British War Cemeteries in Italy. It is a companion piece to another article about life and death behind the lines in Italy. Death Beyond the Front Line- The British at Arquata and Cremona and the Spanish Influenza.

Arrivals in Ventimiglia

Ventimiglia, the Roman Album Intimilium, was the former capital of the Intimilii, a Ligurian tribe. Besieged by the Byzantines and the Goths, and it suffered from the raids of the Lombards. In the 10th century, it was attacked by the Saracens. In 1139 the Genoese attacked by land and sea and forced it to surrender; the count continued to hold the city and countship as a vassal of the victors. In 1505 it was annexed to the Genoese Republic.

The Old Town of Ventimiglia and the River Roya

In Roman times, the Via Julia Augusta ran through Ventimiglia. This important Roman road connected Piacenza to the Varo river (the Var), running along the coasts of Liguria and those of the Côte d'Azur, towards the Rhone. It was a branch of the Via Aurelia connecting Cisalpine Gaul to transalpine Gaul. This route was opened shortly after the conquest of the Maritime Alps against the Ligurian tribes (in 14 BC) by Emperor Augustus. In a state of ruin at the beginning of the second century, it was restored by Hadrian and then by Caracalla in the third century. The route began in Placentia (Piacenza) and, passing through Iria (Voghera), Dertona (Tortona) and Aquae Statiellae (Acqui Terme), descended towards the coast and continued to La Turbie, between Menton and Nice; later being extended to Arelate (Arles), to connect to the Via Domitia (Via Domizia). Along its route it crossed, among others, the Roman centers of Vada Sabatia (Vado Ligure), Albingaunum (Albenga) and Albintimilium (Ventimiglia).. Remnants of the ancient route werte found between Albenga and Alassio (short stretches of the original pavement) and in the Finale area; more numerous, however, are the bridges that have survived (with some modifications) to the present day, as well as the funerary monuments, visible in Albenga. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Via Julia Augusta maintained an important role in communications enjoying efficient management by the monks, first and foremost the Benedictines, for whom a good road system was useful both for the passage of pilgrims and for the exchange of foodstuffs between the Po Valley (with its extensive cultivated lands and the river ports of the Po) and the sea, from which the precious salt came. With the arrival of the Lombards, the Roman city of Ventimiglis was abandoned, and the historic center was established sheltered on the hill and protected beyond the waters of the Roja river. This at least provided some protection from sracen coastal rraids. The ancient upper town, dominated by a magical atmosphere, was the centre of Ventimiglia life until 1800, when progress, embodied by the railway, allowed the resort area along the coast to be reestablished.

The Roman Theatre in Ventimiglia with the coastal railway line behind

The Nizza gate in Ventimiglia

In, 1852, the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Lyon à la Méditerranée was established in Paris. An agreement signed on 19 June 1852 between the Minister of Public Works and the company approved the purchase of various railway concessions made by the company and awarded it the construction and operation of a line from Marseille to Toulon. This subsequently became the Compagnie des chemins de fer de Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée . The first section, sixty-five kilometres long, required major works, in particular between Aubagne and La Ciotat, with the construction of important engineering works, including six tunnels,. On October 25, 1858, the line between Marseille and Aubagne was opened. The second section of fifty kilometres, from Aubagne to Toulon, was opened to a single track on 15 March 1859 despite the importance of the civil engineering works to be carried out and reserved for the French State, engaged in the war in Italy. On 27 March, 1859, the first test run from Marseille to Toulon was made: the train arrived at its destination at eleven in the morning after four hours of travel. To speed up the construction, the works were continued even at night. The second track entered service on 24 April for military transport and on 3 May for the beginning of commercial exploitation which became regular from 28 May 1859. The Marseille-Toulon journey took two and a half hours, with twelve stations along the way.. An imperial decree of 3 August 1859 declared the section of the line connecting Toulon to the Italian border, then located on the Var River, to be of public utility- The entire route was approved in 1860 and work immediately began. 7,000 to 8,000 workers, mostly from Piedmont, Belgium and Germany, were worked on the line With the cessation of the county of Nice to France in 1860, an imperial decree authorized the extension of the section to Nice.. Since the Italian network was in the making, it seemed logical to connect to it by extending the line to Menton and the Italian border. The works were started after the signing of an international convention between the two countries in 1862, The Italian Government received interest of 5% on the international construction costs of the French railways in Ventimiglia station and on half of the costs relating to the buildings for common use, and also received two thirds of the revenue from transport between the border and Ventimiglia by way of toll. .Menton was reached on 6 December 1869, serving the entire French coast from Marseille to 249 kilometres away.

The Railway for Ventimiglia looking back towards Menton and France

The idea of a coastal railway for Liguria was born in 1857 with what was then called the Ligurian Riviera Railway which, begun in March of the same year, was to start from the Varo river (west of Nice), then the border of the Kingdom of Sardinia with France, to reach the Magra river which then marked the border with the Duchy of Modena. This railway was part of the ambitious railway system project considered by Cavour as a determining factor in accelerating the process of Italian unification. At that time, a short section was already in operation in the west of Genoa, between the station of Sampierdarena and Voltri, opened on 8 April 1856, which branched off from the Turin-Genoa line and the speeding up of the process of creating the Kingdom of Italy gave a further impetus to the completion of the work. The Law of 27 October 1860 instituted the Ligurian railway, running along the entire coast, connecting Ventimiglia with Massa and therefore with the already existing railway lines. Construction and operation were entrusted to the recently created Livorno Railways, which after a few was absorbed by the Roman Railways (SFR), which activated the section from Voltri to Savona on 25 May 1868. In November 1868 the line was ceded to SFAI, which already managed the rest of the northern Italian network. On 25 January, 1872, the line was completed reaching Ventimiglia. The international connection (of only 7 km), with the construction of the border station of Ventimiglia, was activated two months later (18 March 1872).The coastal railway was built on a single track due to the technical difficulties of the Ligurian coast. The designers did not paid little attention to the needs of the territories that were crossed, because the line was considered of primary importance for the purposes of military and defensive interests. Another aspect influencing the choice of the original route was the need to build quickly and contain costs, which is why the railway had a tortuous course, ran through rather short tunnels (excavation operations were slow and expensive) and in many cases ran right through towns, cutting them off from the sea (as for example Bordighera and Sanremo). This choice also took into account the fact that at that time most of the transport was by sea, so the route ran practically at sea level, faithfully following the coastline and flanking, where possible, the Via Julia Augusta, uniting over forty small towns, until then difficult to reach by land when not reachable exclusively by sea.

The old Via Julia Augusta running alongside the railway looking back towards Menton

Further down the coast therailway just before Ventimiglia

So when following the Italian debacle at Caporetto, the British and French decided to send reinforcements to the Italians, the coastal route to Ventimiglia was potential route to the Italian Front. The British were already operating a railway route in Italy to the South Italian port of Taranto and from there to Salonika and the Middle East. For many years before the war the normal route of individual passengers between the United Kingdom and the east had been overland by rail to Brindisi, and regular railway services had been run to correspond with the departure or arrival of steamers. In the earlier years of the war a continual stream of military officers, government officials, nurses, small parties of civil and military specialists, and others travelling had travelled the route on thw wat to overseas forces in the east; when the Allied Powers commenced operations in Macedonia small bodies of troops were added to the stream. The normal lines of communication for the British forces were by sea. In the summer of 1916 the activity of enemy submarines in the Mediterranean suggested to the French the idea of shortening the sea passage by the use of a railway route from France to a port in southern Italy, and towards the end of December 1916, after a period during which a limited service had been run, they established a regular service of two trains per day from France to Taranto. To the British a line of communications shorter and safer than the long all-sea route was as necessary as it was to the French. The sea passage from the United Kingdom was much longer, the danger from submarines greater and economy in shipping more important. On 3rd January, 1917, the Director. General of .Transportation. was directed to enquire into the possibility of passing troops and stores overland from a French port on the Channel to the south of Italy and of forwarding them thence to Salonika. The route was approved in principle the development of a new line of communication between the United Kingdom and Macedonia, and thee British sent an expert to Rome to discuss with the Italian authorities possible improvements in the transport facilities. Guy, Calthrop, General Manager of the London and North Western Railway, accompanied by a small party of staff officers visited Paris and Rome to go into the details. Calthrop reported favourably on the scheme , which in the end provided for six trains per day through France to Italy, one or two to be for personnel and the remainder for material. Only drafts and certain units without transport, such as Labour Battalions, were to be sent by rail. Complete units or formations and bulky stores, such as forage, engineer stores, guns, etc., were to continue to go by sea all the way. On the channel, Cherbourg, the only port not already in full use for the B.E.F. in France was selected was the starting point . Facilities were limited. There was a Government dockyard, required for the French navy and a deep-water jetty which had been equipped by the French as a pier to replace berthing accommodation occupied by the British in other French ports, but it was in constant use, and berths at it were rarely be available. Admiralty transport officers considered it inconvenient and in some winds dangerous for large vessels. The possibility of discharging vessels in the roads to lighters and unloading the lighters at an isolated wharf in shallow water was also ruled out by the naval authorities as liable to too frequent interruptions by the weather and for other reasons. There remained the small commercial port, but that could only take small vessels, and being reached through a lock could only be entered or left near the time of high tide. Provided sufficient small vessels were available it was considered that it might be possible to land at most 1,200 or 1,400 tons per day. The railway connections needed much alteration and a large yard was required to hold the empty stock for the personnel and goods trains, and to marshal the trains. From Cherbourg, the route ran through France to Modane and thence by the east coast of Italy through Brindisi to Taranto. It was feared that the railway along the east coast might in places be liable to interruption by shell-fire from enemy submarines, but this route had easier gradients and carried less traffic than the west coast route via Rome and Salerno; the Italian authorities stated that it was guarded by armoured trains. All trains of British traffic for Taranto ran by this route until the end of October 1917, when the service was suspended owing to the despatch of British and French forces to Italy. When the service was resumed in 1918 the route followed by all trains was at first via Marseilles and Ventimiglia, but the personnel trains were by degrees restored to the Modane route, with the material trains continuing to run via Ventimiglia. The total length of the railway journey via Modane and Brindisi was about 1,450 miles. The speed of military trains over the route chosen averaged about 15 miles per hour in France and 17 in Italy. Allowing for halts for meals, etc., amounting to a total of about four hours in every twenty-four, and for stops for railway purposes, the whole journey would last about five days. It was, therefore, considered advisable to arrange for at least one halt of twenty-four hours or more en route to enable the personnel travelling under crowded and generally uncomfortable conditions to leave the train, stretch their limbs, and obtain sleep. In the end the route was divided into three stages, and rest camps, each with a small hospital, established at St. Germain au Mont d’Or near Lyons and at Faenza in Italy. At about a dozen intermediate stations washing and sanitary conveniences were provided and arrangements made for meals. Between rest camps trains normally halted for from half an hour to two hours at intervals of about every three hours, the intervals between halts being as a rule were longer during the night than by day and the longer halts being at the meal stations. Even under the best conditions a small daily percentage of cases of sickness was to be expected ; with large numbers travelling continuously for several days the actual numbers to be cared for would be considerable ; in southern Italy cases of malaria were to be expected. Hospitals were provided at all the rest camps, that at Taranto being not only for European troops, but aso for native labour from the east en route to France. An ambulance coach with medical officer and orderlies accompanied each train of personnel to deal with cases en voute and to clear cases from the intermediate hospitals.

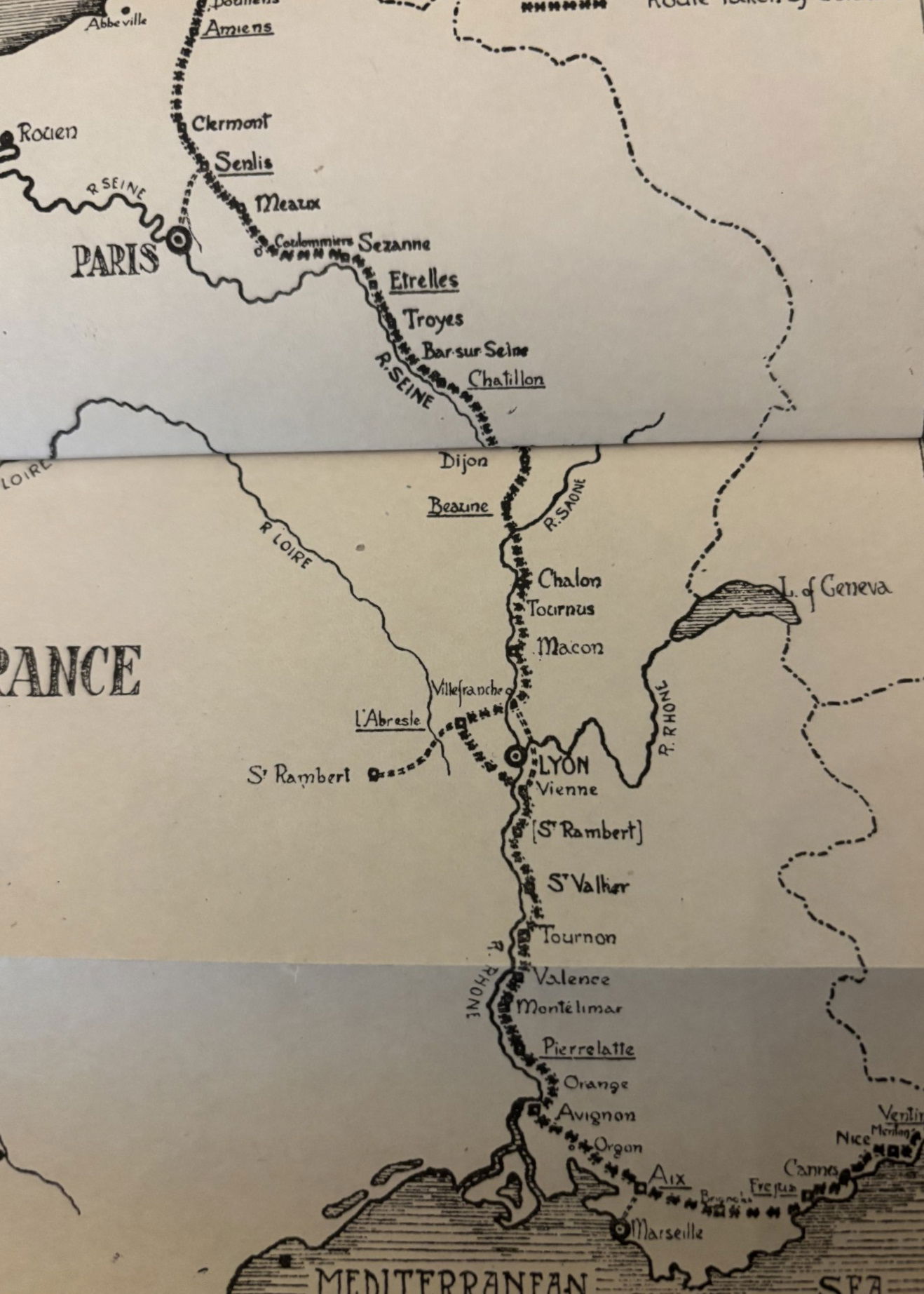

Following the Conference of November 1916 the French had begun in December an examination of the best means of effecting a transfer of forces between the French and Italian fronts. An all-rail route was evidently the quickest and safest, though routes which included sea passages or stages by march were also considered. For an all-rail route the technical railway arrangements on the French railways, and between the French and Italian railway authorities, were matters in which the British were not directly concerned. The distance from the British front in France to a concentration area in northern Italy was from 500 to 600 miles as the crow flies, but the shortest railway route via Modane was about 800 miles and the one via Etaples, the Rhone Valley and Ventimiglia, often followed, was nearly 1,200 mules.

The drawing up of the railway programme was complicated by the fact that in the event of a violation by the enemy of the neutrality of Switzerland a movement to or from Italy might coincide with the concentration of a large force on the Franco-Swiss frontier. Routes had to be chosen which could take additional traffic without over- charging lines already heavily taxed and without interfering with the possible simultaneous concentration. The routes to be used might, and ultimately did, need the construction of raccordements at junctions, additional locomotive water supplies and other technical improvements to enable them to cope with the traffic.

The maximum capacity of the coastal route through Ventimiglia was about 20 trains per day, the section between Ventimiglia and Savona being single line; the capacity of the Modane route through the Mont Cenis tunnel was limited by the electrified section from Modane to Bussileno to a maximum of 21 trains per day. In both cases the trains were limited to a length of 32 wagons and the gross load of 545 tons, giving an average net load of only 260 tons per train. In 1917 the Modane/ Mont Cenis route was already carrying 16 trains per day, the running of which could not be suspended for more than a few days at a time—one of mails and passengers, one to Taranto for the maintenance of the French forces in Macedonia and fourteen of coal. The British traffic from Cherbourg to Taranto was also using this route. The scheme for transporting British and French forces to Italy drawn up in August 1917 provided for two courants, A and B, with the following routes:

Courant A. Dunkerque-either Boulogne or Arras— Longueau-the Ceinture-the main line from Paris to Belfort as far as Troyes—Dijon—Lyons—Marseilles—Nice—Ventimiglia, and thence via Savona and Genoa to Legnago. Courant A was at the rate of 24 trains per twenty-four hours, 16 trains passing to Italy. Of the remaining 8 four were to be unloaded at Nice and the troops after marching across the frontier were to re-entrain at San Dalmazzo-di-Tenda ; the other four terminated at Ventimiglia and the troops were to re-entrain at Savona.

Courant B. Dunkerque — Arras — Longueau — Montdidier - Ormoy — Mareuil — Chalons—Chaumont-Gray-—Bourg-Ambérieu, and thence either via Chambéry to Modane or wa Lyons, Livron and Veynes to Briangon. In Italy Courant B continued from Modane via Turin and Milan to Verona. Courant B was at the rate of 18 trains per 24 hours; 12 continued through Modane into Italy, 6 discharged their loads at Briançon and the troops re-entrained in Italy in the neighbourhood of Pignerol.

So the total number of through trains contemplated was 28 per day, 16 via Ventimiglia and 12 via Modane. When once British and French forces were established in Italy there would be the daily service required to maintain them, which in the case of the British was estimated at 5 trains The despatch of French and British forces was decided on by the two Governments on October 27th. The first contribution of the British was to be a corps of three divisions, but on November 9th, while the first of the three divisions was still entraining, two more divisions with army and corps troops units were placed under orders to join the British Force in Italy. The move, therefore, was not a move of a few isolated divisions but of a whole army, comparable to the move of the British Expeditionary Force from the Channel ports to its concentration area in France in 1914. The army and corps troops included headquarter units, heavy batteries, signal companies, ammunition and supply columns, corps cavalry, air squadrons, anti-aircraft section and other units; the L. of C. services included medical units, hospitals, remount squadrons, ordnance workshops, supply units and others. All these together amounted to some 55 separate units with a personnel of 6,500, over 2,000 horses and mules, and nearly 2,000 tons of stores (irrespective of guns, lorries, caterpillars, cars, wagons and other wheeled vehicles) equivalent to some 50 or 60 trainloads. The two courants commenced to flow on 28th October the earlier movements being French ones. Some British advanced parties started on the 29th followed by the divisional supply column and ammunition subparks of the 23rd Division on the 30th, and then various small parties and trains of supplies and stores in bulk. The entrainment of the 41st Division was suspended from 2nd December to the 8th for railway reasons. The German counter-attack at Cambrai had begun on 30th November, and three courants of French troops were being put in motion towards Amiens and Chaulnes, two of them over part of the route of courant A and the third over part of the route of courant B. Detrainments took place at a number of stations in the Mantova district, the first two divisions to arrive detraining mostly to the west of Mantova and the remaining three divisions to the east of Mantova towards Legnago. The despatch of non-divisional units, L. of C. establishments and bulk trainloads of stores proceeded concurrently with the movement of the divisions; the last entrainments of troops, a group of heavy artillery, were on 17th December, and the last of the army and corps troops detrained on 21st December. The majority of the trains followed the route of courant A via Ventimiglia and usually occupied through marches, but the artillery of the 23rd Division detrained at Nice and marched across the frontier, re-entraining at Savona. From 11th November , six out of the twelve daily through marches of courant B via Modane were allotted to British traffic and thereafter some of the troop trains travelled by that route. Bulk trains of ammunition, supplies and other stores continued to be despatched to Italy all through December. By 51st December the total number of trains for the transfer of the force from France to Italy amounted to 715, made up of approximately 442 troop trains, 102 trains of supplies, 102 of ammunition, 32 of ordnance stores, 28 of engineer stores and 9 miscellaneous trains.

Of course, it was hardly a pleasure trip , it was a long tiring and uncomfortable journey much of which was conducted at night. On 8 November 1917, Private Norman Gladden left Northern France with the 11th Battalion of the Northumberland Fusiliers , they had no idea where they were going – it was rumoured to be Albania. The train passed through the battered town of Albert, through Amiens reaching Paris at dusk, reaching Troyes in the morning and Dijon in the afternoon . During the night they passed through Lyon and the next morning southwards through the Rhone Valley , where Gladden “ gazed with a new delight upon the wonderful old town of Avignon , with its upstanding walls and the impressive bastion of the Palace of the Popes towering above the clustering houses”. During the morning they reached Marseilles , where Gladden saw for the first time the intensely blue Mediterranean, by the evening they wee in Toulon , where the finally realised the destination was Italy . To Gladden’s disappointment they passed the stretch along the French Riviera at night, arriving in Ventimiglia in the morning.

“That evening the train, travelling eastwards, reached Toulon and we knew that Italy was our destination. When we opened the door of our truck on the morning of 11 November the train had halted at a station alongside a tall white flagstaff, from which floated a strange banner in red, white and green with a central shield—the ensign of Italy. We were at Ventimiglia, the first station across the frontier. I was sorry to have missed the French Riviera, which we had traversed during the night, but experienced a naive delight at having thus come to this romantic and beautiful land, a land with which I was to fall immediately in love and to revisit again and again in later years. We were fortunate in the hour of our entry, for the autumn sun shone down upon that lovely coast with a clarity that caused everything to sparkle in its limpid light, and only at the meeting point between sea and sky did there seem to be any gradation between the two shades of blue. The railway line, an ugly mechanical despoiler of the lovely shore, curled in and out, now on rocky slopes poised precariously above the sea, now threading numerous tunnels through the hillside. We passed richly wooded valleys, with occasional glimpses of the peaks of the Maritime Alps towering beyond, and vineyards and orchards filled with vines and fig and palm and many sub- tropical plants, which were new to me. Waters of intense blueness were breaking in lazy white surf along the red-hued rocks, upon which square colour-washed houses firmly stood, their walls often painted with designs that gave a fairy touch to the scene. “

British troops travelling by road, also arrived at Ventimiglia, having driven down the Rhone Valley This was understandable, since the only alternative was driving these early and fairly primitive trucks over Alpine passes.

The route of the 17th Divisional Supply Column down the Rhone Valley to the French Riviera

Trucks of the 17th Divisional Supply Column heading out of Menton and into Italy

“In the meantime, on arriving at Ventimiglia, we parked the lorries on the sea-front. It was a glorious spot for a lorry park; a park that a month previous we could not have dared to dream of. The lorries stood within a few yards of the ebbing tide, and only separated from it by an avenue of large and stately palms that grew on the water's edge. Close on the right the waters of the River Roya quietly and peacefully emptied themselves into the ocean, glad to be at rest at last, and to hide themselves for ever in the bosom of the deep. Behind rose in irregular formation the old town of Ventimiglia, houses of all shapes and sizes clustered together in mad confusion ; those at the foot of the hill being lapped by a sea that in calm weather acted as a magic mirror, and in misty colours threw back an inverted mirage of this quaint old town. To complete the picture, a back- ground of green, wooded hills, and near the far, far horizon, snow-peaks that faded away into the distant Alps. “

Trucks of the 17th Divisional Supply Company parked at Ventimiglia

At Savona the British troops either rejoined the Italian railway system or headed by road to the concentration area around Mantova.

Departures - Bordighera

Unfortunately a rather hazy view over Bordighera

For those soldiers, unfortunate enough to have been wounded in the battlefields of Asiago and the Piave, the resort of Bordighera on the Italian Riviera was a stopping off point on the evacuation route to Marseilles and then back home to the United kingdom. Unfortunately, some wounded or sick soldiers Bordighera was the final destination of their as evidenced by the presence of a British War Cemetery in the town.

The village of Bordighera had its origins in the fifth century BC as a fortified hill top Ligurian village based on agriculture and sheep farming . In Roman times, the Via Julia Augusta passed below the village, along the coast although the precise route seems unknown.In the early years of the fifth century a hermit religious named Ampelio from Egypt landed nearby, he lived in a cave among the rocks, on which the small church of Sant'Ampelio was built. A monastic priory dependent on the abbey of Lérins was later built here. However the coastal site suffered continuous attacks fro the Saracens and was progressively abandoned. In 1470 some local families decided to rebuild the town as a fortified village, high above the hill and overlooking the sea. Things did not stay peaceful for long, in 1543 the Turks besieged Nice, then pushed towards the Ligurian Riviera, besieging first Bordighera, capturing and enslaving men, women and children. In 1818, the Napoleonic road, "La Corniche" reached Bordighera, facilitating the connections and development of the new districts near the sea, the Borgo Marina. The nineteenth century was the golden age of the city, thanks in part to Giovanni Ruffini's novel Doctor Antonio, which, published in 1855 in Edinburgh, aroused the interest of the British in the Bordighera. In 1860 the first hotel, Hotel d'Angleterre (now Villa Eugenie) opened , welcoming a first illustrious guest, the British Prime Minister Russell. With the connection of the French and Italian railway systems, in 1872 the railway station was inaugurated, which connected Paris and Bordighera in just twenty-four hours. With the opening of the Calais-Rome Express line, in 1883, the time was further shortened and twenty-four hours were needed to connect London and Bordighera.

Bordighera- the entrance to the Citta Vecchia

Bordighera became a favourite with a certain type of comfortably off British tourist. There was a period at the end of the 19th century, during which the English guests of Bordighera, staying at the Hotels and villas hidden among the olive trees, may have been as many as 3,000, outnumbering the local population which at the time amounted to around 2,000 inhabitants. In Bordighera, the British had their own Anglican church, shops, banks and social club, they even had their own plot in the cemetery. As mentioned, this British invasion was partly due to “Doctor Antonio". Ruffini was an Italian patriot who wished to secure British support for Italian Unification and wrote the work specifically to win over the British market to the cause. In brief, Doctor Antonio is fighting against the rule of Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies, he meets and falls in love with the daughter of an English aristocrat. He eventually is compelled to give her up and return to fight and die for the cause of Italian unification. The book certainly gives some fine descriptions of Bordighera, although , one wonders if it single handedly created the English tourist trade. Was Ruffini a 19th Century influencer, describing the view over Bordighera:

“There was not a ripple on the sea, whose bright blue was only now and then chequered by broad white streaks— milky paths on the azure — some stretching forth in straight lines, others winding forward in graceful zig-zags. Battista and his comrade put forth the strength of their brawny arms, the former keeping his eyes carefully averted from Miss Davenne, who lay back on the cushioned seat, parting the water by the boat’s side with her delicate fingers, deep in pleasant imaginings, it would seem, from the half smile on her lips. Swiftly they glided past the Cape of Bordighera, and then a new and splendid panorama opened out before them. A glorious extent of hilly coast against a background of lofty mountains, stretched semicircularly from east to west, broken all along into capes and creeks, and studded with towns and villages, full of original character,— Ventimiglia, with its crown of dismantled mediaeval castles, — Mentone, so gay on the sunny beach, well named Roccabruna, all sombre hues and frowns,— Turbia, and its Roman monu-ment, a record of the greatest power on earth, covering with its shadow the lilliputian principality of Monaco below, — Villafranca and its lighthouse. Further on, running south- ward, loomed vaporous in the distance, the long, low strip of French shore, with Antibes at its extremity; and further still, in the west, the fanciful blue lines of the mountains of Provence. Here and there a snowy peak shot boldly above the rest; some hoary parent Alp, one might fancy, looking down to see that all went right among the younger branches. “

If Ruffini provided a written encouragement to visit Bordighera , visual stimulation may have been provided by the paintings of Claude Monet. Between January and April 1884, Claude Monet, father of Impressionism, stayed in Bordighera. His visit was an inspiring experience that gave rise to some of the most fascinating works of his career. Attracted by the southern light and the intense colors of the landscape, Monet found in Bordighera an inexhaustible source of wonder. "Everything is admirable, and every day the countryside is more beautiful, and I am bewitched by the country," he wrote to his Parisian merchant Durand-Ruel. Monet settled at the Pension Anglaise and worked "en plein air", capturing on canvas the infinite shades of blue of the sea and sky, the lush green of the vegetation and the bright colors of citrus fruits. During his stay, Monet explored the Via Romana, the Old Town seen from the Torre dei Mostaccini and the Vallone del Sasso, even going inland. The landscapes of Bordighera fascinated him, stimulating him to represent the beauty of the place with a unique mastery. In just 79 days, Monet created thirty-eight canvases in Bordighera.

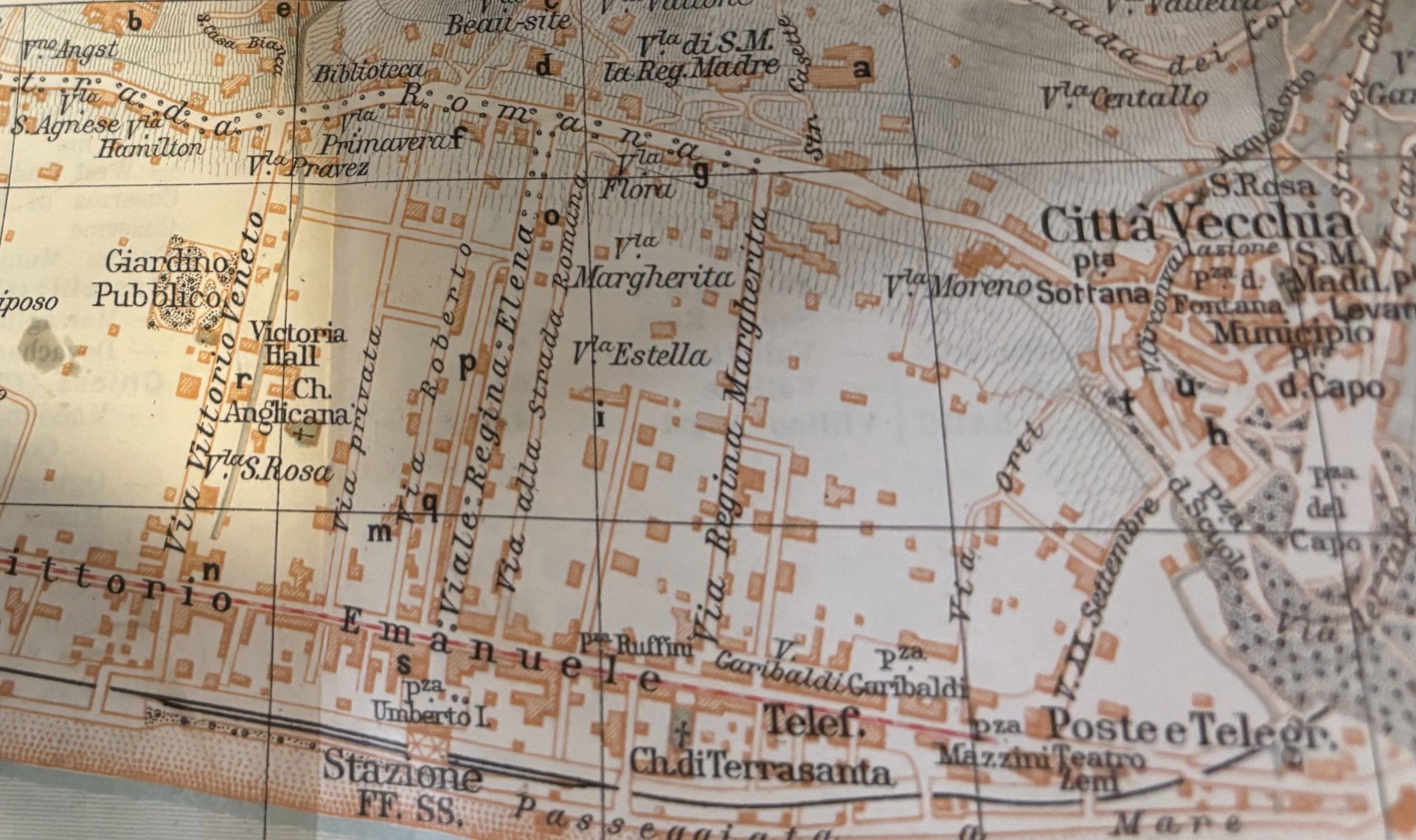

The via Romana in Bordighera. On the left at b), the Grand Hotel villa Angst, at e) the hotel Belvedere, c) and d) the Hesperia and c) the Royal and past the Villa Regina Margherita to the Citta Vecchia

A choice of hotels in Bordighera from Bradshaw's Guide

The former Hotel Angst, home of the 62nd General Hospital now being converted to luxury apartments

The Hotel Angst

With the railway running along the coast and separating the town from the coat, more grand hotels and villas were built along the via Romana, which ran inland from the old town. Typical of such villas, was villa Bischoffsheim at number 38 via Romana, built for a banker Raphael Bischoffsheim in 1873 , designed by the noted French architect Charles Garnier . Among the famous guests hosted here were Louis Pasteur and the future Queen Margherita of Italy . In 1896, it was bought by Lord Claude Bowes- Lyon , 14th Earl of Strathmore , and was visited by his daughter Elizabeth, the future Queen of England . In 1914, the Bowes- Lyon family sold to the by now widowed Queen Margherita . In 1914, the dowager Queen ordered the construction of a new villa in the go rounds of the Villa Etelinda , which was inaugurated in 1916 .Neighbouring hotels were the Hotels Royal and Hesperia. and further along the via Romana, the Hotel Belvedere and the Hotel Villa Angst. On the other side of the road the Hotel Londres was built. Together they provided several hundred rooms . When war broke out , the broad tree lined via Romana, with its grand hotels provided an ideal location for military hospitals. The 62nd General at the Villa Angst The hotel was built in 1887 by the Swiss entrepreneur Adolf Angst, who wanted to open a large luxury hotel, his hotel was a great success, being frequented by a mainly British clientele in the winter months. In 1900 Queen Victoria reserved the entire structure for herself and her entourage for a season, although her trip was later canceled due to the Second Boer War.

The War Establishment of a general hospital was 32 medical officers, 2 quartermasters, 3 Chaplains , 73 nursing staff and 203 Oher Ranks . All told some five hundred British medical personnel would have swelled the peacetime British population of Bordighera. Those were off course theoretical levels. In reality, the demands of the war and the need to keep the frontlines fully staffed might have meant that the General and Stationary hospitals in Italy, were staffed at a much lower level than the establishment provided.

Dorothea Matilda Taylor acted as Principal Matron in Italy for Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Nursing Service, , she therefore got to visit all of the British hospitals at the front and in the Rear areas of Italy and left some interesting portraits of them.

“Bordighera-A few days after my return I went to Bordighera: the drive down from Genoa being most beautiful. The road is by the sea the whole of the way; up steep slopes, round sharp curves, and down steeper hills on the other side; the wonderful blue Mediterranean Sea being always in view. I have gone down that road on dull days; on many sunny days; by moonlight; and when the sun was setting; and each time thought it more beautiful than the last. There are groves of pine and olive trees, and wonderful gardens where roses and carnations grow, also plantations of palms. It is said that a shipwrecked sailor who was rescued and landed at Bordighera took as a thanks-offering palm leaves to St. Peter’s at Rome, and ever since then palms are sent to St. Peter’s from Bordighera for Palm Sunday. There is an ever-constant change of view as you go along, and quaint little villages where the inhabitants can be seen at work, making pottery, drawing in fishing nets, or building boats. At Bordighera it was warm and sunny, with a profusion of roses, mimosa, and heliotrope, to greet one. No one wore great coats, so that we felt rather ridiculous in our fur coats and the warm clothes so necessary at the time of the year in the North.

There were two large General Hospitals at Bordighera situated in six hotels, also some under canvas. They were exceedingly nice and the wards were always bright with flowers. Some of the hotels had nice gardens so that the patients could have their beds taken out in the sun, and those who were well enough used to go and sit by the sea. “

Unfortunately, usually where you find British military hospitals, British War Cemeteries are not far away and Bordighera is no exception. On the eastern side of town near the river, is the British War Cemetery. It is next door to the Bordighera Cemetery, where many of the peacetime British residents who did in Bordighera are buried.

The British War cemetery in Bordighera

From the cemetery records it is not always apparent from what the soldiers died from . Cause of death is given in few cases . Where the detail died of wounds is given , this might often be several days after an engagement at the front line. Otherwise they died of sickness, or in more specific detail died of influenza or pneumonia, if the specific detail is given. The patterns of the war in Italy can be traced from the burials in Italy, where there were three main periods of combat, December 1917 to January 1918, in the area of the Montello on the River Piave, June 1918 on the Asiago plateau and October and November 1918 on the Piave and at Vittorio Veneto. When they arrived in Italy, the British Divisions were deployed in a defensive line on the River Piave. Private Frank Gentleman aged 21 from Southall, Middlesex died of wounds at Bordighera on 30th December 1917, he has served with the 26th Battalion Royal Fusiliers. The battalion formed part of the 124th Brigade of the 41st Division. The division completed its concentration in the Mantova area by 18 November. 124th Brigade then undertook a five-day march of 120 miles) to take up positions between Vicenza and Grisgnano. The gruelling march was conducted in battle order with advanced guards and night outposts. On 1st December the Brigade took up a sector of the front line along the River Piave around Nervesa, and remained there for the rest of the month. Private William Stevens of the 13th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry, died of wounds on 14 January 1918. The DLI formed part of the 68th brigade of the 23rd Division. Also deployed on the River Piave were the 1st and 12th Battalions of the East Surrey Regiment, the 1/6th battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders as divisional Pioneers and the 23rd Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment. The fighting was by no means intense, but the British suffered casualties from Austrian shelling and sniping from the opposite bank of the Montello. For more on the British on the Montello, see On the trail of Edward Brittain- Along the Piave and on Montello.

The view from the British positions across the Piave at Montello. Typical of where the first British casualties in Italy were taken

In March 1918, the British began to move to the Asiago Plateau, things remained relatively quiet until the Austrian offensive in June which caused considerable casualties. Private Alfred Fearnley, aged 25 from Sheffield, serving with 8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry died of wounds at Bordighera on 23rd June, Part of the 23rd Division, the 8 KOYLI were in reserve about half a mile behinf the lines when the Austrians attacked. At 7 am , 4 and half Austrian regiments attached the British positions on Sisto Ridge, After a fierce battle, the Sherwood Foresters who held a thousand yard front, were driven back and suffered severe casualties. During this engagement, Vera Brittain's brother Captain Edward Brittain was killed. The British regrouped and counter attacked, which was when the 8 KOYLI was bought into the fighting. See In search of two Buxton heroes on the Altopiano.

The British positions at Sisto Ridge the site of bitter fighting on 15th June 1918T

Among the British graves, there are also the graves of several Austro- Hungarian soldiers, clearly prisoners of war taken by the British, who required medical attention. By the dates of death in late June 1918, they were most probably casualties of the fighting on the Asiago plateau . Generally the British handed their prisoners over to the Italians and these are apparently the only Austro-Hungarians buried in a CWGC cemetery in Italy. Nearer to the front in Asiago, there were Austrian war cemeteries. In Bordighera, so far from the front it fell to the British to bury their former enemies.

Austrian graves at the British War Cemetery in Bordighera

According to the British records Private Bizilj belonged to the 17th Austrian infantry Regiment. This regiment belonging to the 12th Infantry Brigade – 6th Infantry Division – III Army Corp, was predominantly Slovenian (estimated at 86% Slovenian speaker). From March 1918 Infantry Regiment No. 17 was stationed near Canove, southwest of Asiago, where it faced by British units of the 23rd and 48th Divisions, who repeatedly attacked the line held by the 17th Infantry Regiment the following month. When the last Austro-Hungarian offensive broke out on 15 June 1918 with the Second Battle of the Piave, the regiment was again at Canove after a short break. The attack collapsed within a few hours due to a lack of artillery support in front of the lines of the British 23rd Division near Cesuna. With heavy losses, the attack had to be called off just 24 hours later. Private Hermann Kpacie of the same regiment may also have been Slovene in origin . According to the British Official History, the Austrian 6th, 12th, 74th, 27th, 17th, 127th and 81st Regiments were also involved in the attack on the 48th Division. Members of some of these regiments are also buried in Bordighera.

View of Asiago from the British lines- the area saw bitter fighting between the British and Austrians in June 1918

Coming from further away than Slovenia , was Private Samuel Urayah Thompson who died aged 25 at Bordighera on 26th April 1918 . He served with the 6th Battalion of the British West Indies Regiment, the battalion was raised from voluntary recruitment in Jamaica between November 1917 , with an establishment of 36 officers and 1656 men.After training at Swallowfield Camp, the contingent sailed from Kingston on 30 March 1917 arriving in Brest on 19 April 1917.An outbreak of measles and broncho-pneumonia on board caused some of the serious cases to be landed on the islands of Martinique and St. Lucia. After serving on the Western Front , the 6th Battalion had arrived in Taranto on the heel of Italy on 29 January 1918. The battalion stayed there for just two months , before receiving orders to proceed to Abbeville on the Western Front During the time in Taranto a number of men died in the Native Labour Hospital. They entrained on 19th April 1918, Eleven other ranks were left in the hospital a Faenza as the train travelled up to Marseille, Presumably Private Thompson was sufficiently serious to be moved from Faenza to Bordighera where he died. In total approximately 15,600 men served in the British West Indies Regiment. Jamaica contributed two-thirds of these volunteers, while others came from Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, the Bahamas, British Honduras , Grenada, British, the Leeward Islands, Saint Lucia and St Vincent. Two hundred and sixty two men lost their lives overseas during the conflict, 105 to enemy action and 157 dying of disease; a further 573 were wounded.

Sometimes the hospital staff in Bordighera were patients in their own hospitals and died, Private Frank Ball . aged 23 from Kettering was attached to the 62nd General Hospital when he died on 19th February 1918, Sergeant Francis Murray McKenzie from Belfast of the 66th General Hospital died of an accident on 1 January 1918. Sergeant Gustave Remmos of the 62nd General Hospital from Manchester died aged 35 of accidental injuries at Bordighera on 18 August 1918.

Staff Nurse Rachel Ferguson was born on 29 December, 1886, in Ballygoney, County Londonderry into a farming family, Rachel was the youngest of eight children. Initially stationed in Salonika, Greece, she became unwell in 1917, but returned to extend her service by six months, or until her services 'were no longer required, whichever should happen first'. Rachel was transferred to Italy in November 1917, where she served until her death from pneumonia in June 1918. Rachel was educated at Ballygoney National School and Lady’s School, Cookstown. She trained at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast where she qualified as a Staff Nurse in 1915, and was notified of acceptance for service on 10th September 1915, and she joined the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (Q.A.I.M.N.S). She arrived in Salonika on 6th June 1916 where she was posted to No. 28 General Hospital. While in service, she became unwell and was admitted to the Red Cross Convalescent Home on 15th June 1917 before being transferred to a hospital ship on 29th June. She re-joined No: 28 General Hospital for duty on 8th July 1917. With her contract due to expire on 12th November, she submitted an application on 9th October to extend her service by six months ‘Or until my services are no longer required, whichever should happen first. Rachel embarked on H.M. Transport ‘Abbassich’ for Italy to work in No: 62 General Hospital on 7th November 1917. They disembarked at Taranto eight days later. Staff Nurse Ferguson served in Italy until May 1918. In May she was given leave for fourteen days. She returned to Coagh. It was the only holiday she got during her three years’ service abroad. She re-joined No. 62 General Hospital on 25th May 1918. On 26th June she was admitted to the hospital as a patient, suffering from bronco-pneumonia. Staff Nurse Rachel Ferguson died of pneumonia later that day on 26th June 1918 in Italy. In a letter received in Coagh on Thursday 27th June, she wrote that she was in the best of health and had signed on for the duration of the war. This was followed, some hours later, by a War Office telegram announcing her death from pneumonia.

Captain George Elphinsone Keith qualified as a Doctor of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1887, He held appointments in Edinburgh and then went to New York, where, after taking the M.D. degree at the Long Island College, Brooklyn, became house surgeon at the Woman’s Hospital. George accompanied Lord Randolph Churchill when he went around the world in his vain search for health. He then settled down in Manchester-square, London, where he devoted himself more especially to mid-wifery. He also became part author of a text-book on abdominal surgery, and for 10 or 12 years devoted a large part of his time to the treatment of cancer by injection, the early account of the work being contained in Cancer: Relief of Pain and Possible Cure. George served as a Medical Officer for the Red Cross, 15th Detachment, City of London. He joined the R.A.M.C. in July 1915, and was promoted to Captain in 1916. He entered the war on H.M.H.S. Britannic and was on-board when the hospital ship hit a mine, laid by the U-73, in the Kea Channel, in the Aegean Sea sinking 55 minutes later, killing 30 of 1,066 people on board;. 1,036 survivors were rescued from the water . Unfortunately. George later died of pneumonia, following influenza, at No 62 General Hospital,