Above Menaggio on the Northern Defensive Line

Most people go the Menaggio on Lake Como for a stroll along the lake side , to take in the lovely views across the lake , eat some lunch or have an aperitivo as the sun goes down. Or you can head in the opposite direction away from the lake and up into hills to find another part of the Northern Defensive Line.

If you are in Como, you can get to Menaggio by road or by a boat up the lake. By road, a car might be the easiest, although there is a perfectly good bus service along the same road, which given the traffic on the lake side road, might not take much longer than a car. The C10 local bus leaves from outside Como San Giovanni Station, check the timetable but it seems to run every couple of hours from Como to Colico. You need to buy a ticket at the bar inside the station. The journey takes about an hour to Menaggio, try and sit on the right hand side of the bus if you can, to get the best views as the bus passes through Cernobbio, past the Villa D’Este, above Moltrasio, and through Argegno and Lenno which some superb views. It must be one of the prettiest public transport routes around. The alternative would be to get the boat from Como, although it takes substantially longer it is an experience in itself. Time it right and you could get the boat there and the bus back.

For at least some of its route, the bus follows the route of the former via Regina. In protohistoric times, Como was an important centre for trade between Etruscans and Celts, especially from the fifth century BC, with the decline of the ancient Greek Colony of Marseilles and the shift of commercial traffic to the Alpine passes. From Como the trade route with the Celts led to Lugano and the Monte Ceneri pass, and from there to Bellinzona, an important centre of Golasecca culture. The road finally led to the San Bernardino and Gotthard Passes. The shore of Lake Como was well known and frequented in ancient times, sources mention the names of the peoples settled on its shores: the Ausuciates of Ossuccio, the Aneuniates of Olonio, the Clavennates of Chiavenna and the Bergalei of the Bergaglia valley. At the time of the Roman conquest of Como, the territory was well organized and 28 castles depended on the oppidum of Como. The importance of Via Regina diminished when the Rhaetians descended from the mountains in 89 BC and tried to drive more of the trade into their own territory. After the transformation of Como into a Roman colony by Julius Caesar, a policy of building new settlements towards the Alps and the reconstruction of the road network to facilitate Alpine transit was part of this political and social context, . In 15 B.C., Drusus and Tiberius conquered the entire Alpine arc , establishing the borders of the Roman Empire up to the Danube. In 12 B.C., the road from Altino to the Reschen Pass and then down into the Danube valley was also begun. The construction of the Roman Via Regina belongs in this historical context. The name "Regina" probably derives from the toponym "Rezia", as the road led, through Valchiavenna, to this Roman province. Perhaps the route was secondary to the lacustrine route from Como or Bellagio, to Samolaco at the Northern End of Lake Como and the road was used only for local trade. The Nautae Comenses managed the trade and were the absolute rulers of the lake. When Milan became the capital of the Western Roman Empire, the Como was endowed with broad powers in controlling navigation.. The first documents that call it via Regina are the municipal statutes of Como of 1335, while previous deeds refer to the via Regia . The Via Regina is documented by the tabulae geographicae, Roman military maps transcribed in the third century.

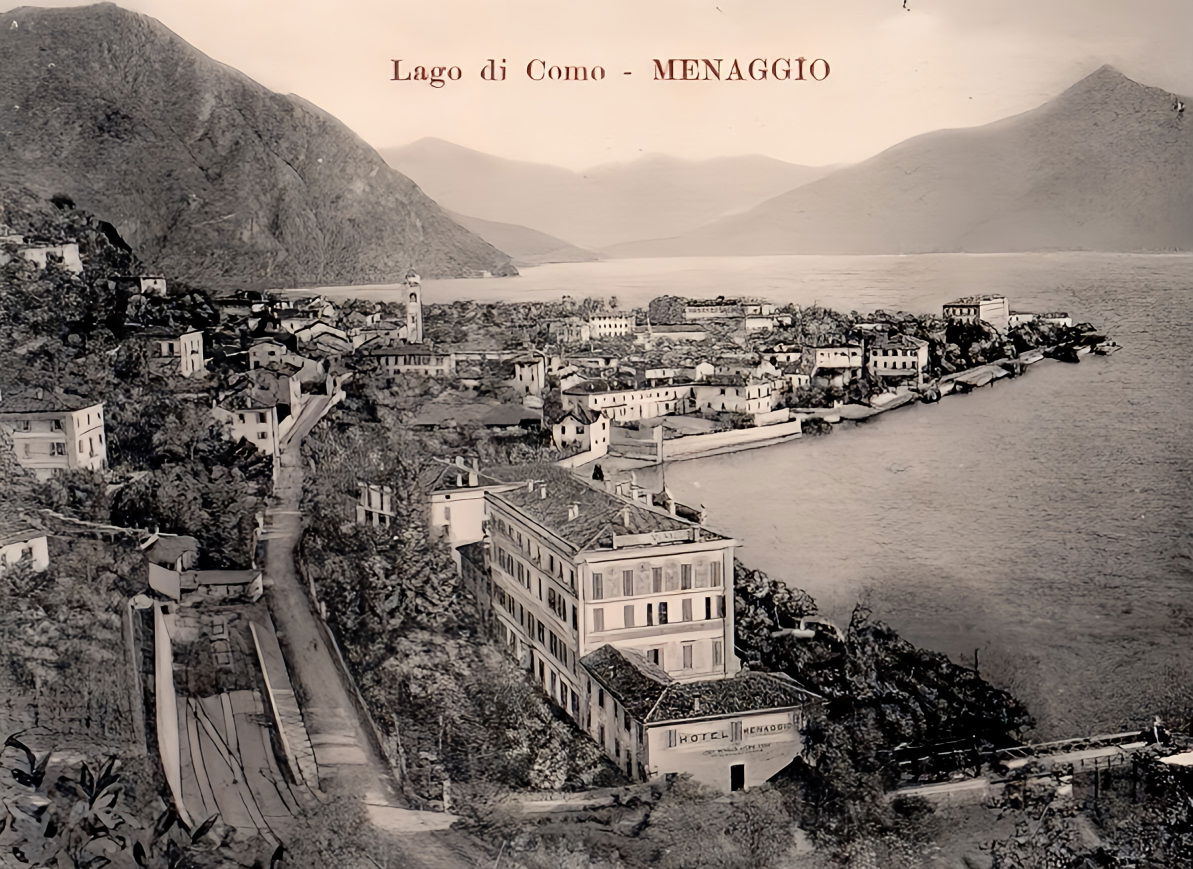

Menaggio by the lake

Menaggio held a strategic position on the via Regina. The territory was originally inhabited by pre-Indo-European Ligurian populations, to which nomadic populations of Celtic origin were grafted, giving rise to the Golasecca culture. The settlement by some tribes of Gauls towards the end of the fourth century B.C. was followed, with the victory of 196 B.C., by Claudius Marcellus against the populations of the Insubres and the Comensi, and the start of period of Roman domination. In 386, the foundation of the Diocese of Como led to the establishment of Menaggio at the head of the parish church of the same name, governed by the presbiter of the church of Santo Stefano. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the territory was invaded first by the Goths and then, in 535, by the Byzantines. They were succeeded in 568 by the Lombards, who endowed Menaggio with a signal tower. After the construction of the castle in the10th century during the ten-year war Menaggio sided with the Milanese and, in 1124, was attacked by the Comasci.

The remains of the castle of Menaggio

In the 1140s Conrad III of Swabia granted Menaggio as a fief to Ardizzone de Castello. In the thirteenth century numerous families of the Como and Milanese nobility fought it out. In 1295 Menaggio was again attacked and this time conquered by the people of Como, who evicted the feudal lord Littardo de Castello (who took refuge in Bellagio) and handed over the castle to Matteo I Visconti. The link between the Via Regina and Menaggio is found in the Statutes of Como of 1335, which mention Menaggio as the locality in charge of the maintenance of stretches of the road.

Between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, Menaggio with its strategic position was guaranteed the control of the tolls on transport. In the sixteenth century, Menaggio became the object of expansionist aims by the Graubünden of the Republic of the Three Leagues, who controlled the city of Lugano. After they had burning the town twice in 1516 and 1521, a further attack in 1523 led to the destruction of the castle, leaving just the remains which can be seen today. With the expulsion of the Grisons by the Milanese, Menaggio returned to be part of the Duchy of Milan until the end of the eighteenth century. The period of Spanish domination, was characterized by two centuries of brigandage, then from 1714, by a period under the Austrians. Administrative reorganization under the

Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy established the annexation of the municipalities of Croce, Loveno and Griante a decision that was revoked by the Restoration. After the unification of Italy, in the Belle Époque, Menaggio saw the construction of numerous villas (especially in Loveno) and luxury hotels such as the Grand'Hotel and the Victoria.

via Calvi with the Church of Santo Stefano at the end

To get to Croce from the lakeside, you can walk through the piazza and up via Calvi, which is now a pedestrian area of bars, restaurants and shops. At the end of via Calvi is the Church of Santo Stefano, which is worth looking inside. Although the present church dates from 1618, with subsequent modernisations , it is on the site of historic older churches. The church is famous for only having a replica of its most famous painting, Bernardino Luini’s Madonna, the original of which is in the Louvre. Since these pages are also following Bernardino Luini , a small digression seems worthwhile.

Bernardino Luini's Madonna in the Church of Santo Stefano- the original is now in the Louvre

This small panel painting on poplar ( 0,8 m by 0,58m) now known as the Madonna of Menaggio was commissioned by the Calvi family of Menaggio for the Church. The inhabitants of Menaggio decided to present this rather precious painting to the Austrian plenipotentiary Karl Gotthard von Firmian , in return for doing them the favour of moving the prefecture from Tremezzo to Menaggio . Some customs in Italy have a long history . Firmian who was a noted art collector died in 1782, and his collection was auctioned in Milan. The Luini was purchased by the Visconte Giuseppe Arconati Visconti, a local noble. When he died it passed to his son Gianmartino, who married a Frenchwoman Marie- Louise Peyrat in 1873. Gianmartino died three years later in 1876 and Marie- Louise inherited his collection of art, which she donated to the Louvre in 1914. And so the Madonna of Menaggio now hangs in the Louvre, with just a photographic reproduction in Menaggio.

Bernardino Luini's " Madonna of Menaggio". Unfortunately a copy , the original is in the Louvre

On the left side of the church is the via Enrico Caronti, turn right and uphill to via Castellino da Castello., this is the original core of the medieval village of Menaggio, which not unnaturally leads up to the castle.as mentioned above, there is not really much left of the castle apart from the outer walls, it having been destroyed by the invading Swiss. At the crossroads with Via Strecioum, take the long staircase on the left (Via Rezia) which ends at an underpass. Once through the underpass, take Via Monte Grappa, which after 300 m emerges onto state road 340, and cross it. After climbing the short staircase, until reaching a sign for Pedestrian cycle track to Porlezza.

via Rezia - the steps up beyond the castle

The Pedestrian cycle track to Porlezza is former railway so it is a rather gentle assent towards Croce. In the second half of the nineteenth century, with the rapid development of Italian railways and the opening of the Gotthard tunnel the prospect of connecting Central Europe with the Lombard lakes opened up,: the aim was to guarantee a modern transport service, replacing the horse-drawn diligence. The project was to connect the lakes with railways and boats, connecting Menaggio with Luino on Lake Maggiore and with Lugano, in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland.

The former railway line from Porlezza on Lake Lugano to Menaggio

Two old views of the Menaggio - Porlezza railway, when it was still working

The railway connection between Menaggio and Porlezza, at the eastern end of Lake Lugano, allowed connection the boat service from Lugano. The railway was short, just over twelve kilometres, characterized by a considerable difference in height: the difference in altitude between the two lakes was more than seventy metres. Additionally the railway had to bypass the smaller Lake Piano along its route , which the railway . Feasibility studies and the construction works, funded by both public and private, Italian and Swiss institutions (in particular the Banca della Svizzera Italiana based in Lugano), were completed in the summer of 1884 by the engineer Emilio Olivieri.. The cost of constructing the network, including the superstructure of the railway, amounted to 1,108,901.71 francs, equivalent to 1.2 million lire, an expense of around 100,000 lire per kilometre. A Royal Decree of 24 March 1881 authorised the Banca della Svizzera Italiana to operate in Italy and the Bank established the Società di Navigazione e Ferrovie del lago di Lugano (SNF), based in Lugano, which opened to public service on 17 November 1884. In 1885, a similar line opened linking Luino on Lake Maggiore with Ponte Tresa on Lake Lugano. It was then possible to get a boat in Locarno and transfer by train to Lake Lugano and from there to Lake Como via Porlezza, which was a great tourist route connecting the three lakes with onward connections to Milan.

The railway line is now a cycle path

Consulting Bradshaw’s 1913 Continental Railway Guide, it gives the time table that leaving Luino on the 12.30 train, arriving at Ponte Tresa at 1.10 in time for the 1.15 streamer for Lugano, arriving at 3pm. There was a leisurely wait until the 3.45 ferry started its voyage to Porlezza, connecting with the 5 pm train for Menaggio, arriving in time for an aperitivo at 5,50,. A six hour trip taking in three lakes, or breakfast on Lake Maggiore and aperitivo on Lake Como.

Bradshaw's 1913 Continental Railway Timetable, showing the Menaggio- Porlezza line and connections with the ferries

At Menaggio, tourists could stay in the beautiful hotels ,the Grand Hotel Menaggio “near to the train station- Surrounded by a beautiful garden which gives right to the Lake” and the Victoria “every modern comfort. Open also during winter. Tennis, Golf, Motor Launch, Fishing, Lake Baths and Drives” at nearby Tremezzo was the Hotel Bazzoni & Du Lac and the Tremezzo Hotel , adjoining the Villa Carlotta. The Lake proved highly popular with upper class British., Germans and Russians. The golden age of tourism, and the railway ended with the outbreak of the First World War; when the former patrons of the Grand Hotels on Lake Como started fighting each other, The British and Germans returned after the war, then the Germans occupied the best hotels during the next war. The Russian aristocrats never returned, replaced later in the century by gangster-oligarchs who now find their Lakeside properties sequestered.

The Belle Epoque in Menaggio

The railway board of directors decided to start negotiations for the sale of Menaggio-Porlezza and the Ponte Tresa-Luino lines, which were no longer profitable. Further economic difficulties arose with the competition from the first buses, which cost less and were faster in a parallel service. To aggravate an already disastrous situation, the Fascist autarkic policy in the 1930s imposed the feeding of locomotives with domestic peat instead of imported coal, leading to a further increase in prices. So on 31 October 1939 the Menaggio-Porlezza railway ceased operations. . At the end of the Second World War, it tried to relaunch without success and has now been replaced by a very pleasant cycle-path.

The old railway tunnel

Inside the old railway tunnel

The railway heads for Porlezza

Once through the railway tunnel, there is a sharp left to another gentle path leading up by the side of a small stream to Croce, it emerges in what used to be a Tiro Segno (shooting range) , of which only the walls remain and now converted into a nice looking outdoor gym , a mountain bike practice track and as a sign of the times a Padel tennis club. Walking through the car park , you turn left and walk up the hill towards the traffic lights and the church. Croce at 393 m is the highest village in the municipality of Menaggio, a former agricultural village, with a piazza in where the rites of haymaking, threshing and harvesting concluded. It is worth taking a look at the historic centre.

There is handy bar, just by the traffic lights to recharge on coffee, water or ice cream. Definitely worth using the traffic lights to cross the road, since the road is curved with a lot of fast moving traffic.

The path up to Croce

Once across the road follow via Wyatt and the big signpost Golf, and follow that road passing by an interesting communal washing building, until you get to the junction with via Padre GB Pigato again the trenches are well sign posted.

The Communal washing house

Follow the asphalted road until it enters the woods and becomes a woodland track, about one hundred metres further you reach a very informative sign of the trench networks. The trenches have been restored and maintained by the local Alpini and are in a good state of preservation.

Map of the trench system

The entry to the trenches

Follow the map to make sure you do not miss any of the trench sections although they all look pretty similar. There are communications trenches, fighting trenches, ammunition deposits, underground dormitories and even latrines, all dug in to the rock and then reinforced with the ubiquitous concrete of the Northern Defensive Line. Compared to the badly drained, wood lined trenches on the western front, these trenches seem positively luxurious . Presumably when it rained they still filled up with water, but otherwise conditions would have been markedly better than in Flanders. The Italians bought their flair for digging trenches in the rock , or using natural lie of the land reinforced with concrete to the trenches which the British divisions in Italy, later occupied on the Montello and the Asiago plateau. In terms of Allied cooperation, in the First World War, perhaps the Italian should have been responsible for all the trenches.

A communications trench

Bunker and frontline trench

Underground dormitory

The first thing you observe is that all the trenches actually face the Lake and Italian territory. Just to refresh, the purpose of the Defensive line was to defend against a possible German or Austrian invasion of Italian territory through Switzerland. The planners deemed it unlikely that substantial enemy force would come over the mountains behind the trenches, instead the risk of potential invasion was through the valleys. In this case the fairly gentle and accessible valley from Porlezza down to Croce and the lake side at Menaggio. So at Croce, the trenches and firing positions overlook the road down from Lugano, which it would have been necessary for any large invasion force to use. If the Germans or Austrians had sent forces over the mountains they would have been able to attack the Italians from the rear. In the end the feared invasion never happened. The Swiss maintained a state of armed neutrality and defended their frontiers from both the Allies and the Central Powers. The Austrians already had two fronts with Italy and therefore had little incentive to violate Swiss neutrality and invade Italy through the Ticino. The Schlieffen plan to invade France, had involved an alternative route through Switzerland, but the Germans had judged Belgium an easier option; however, since Italy had been one of the Central powers at the beginning of the war, it is not clear whether the Germans had bothered with any invasion plan.

Defending the road down from Switzerland

In the unlikely event the Germans would have entered German speaking Switzerland while the Swiss retreated to the Alps. The prospects of getting easily through the Alps would have been difficult. In the Second World War, the Swiss planned to blow up the Simplon and St Gotthard pass tunnels and presumably would have done the same faced with a German invasion in 1916 or 1917. In any case , while the German speaking parts of Switzerland might have had some sympathy with the Germans, any invasion of Italy would have had to sass through the Italian speaking Ticino, which was definitely not friendly towards the Germans. In the even the Italians would have entered the Ticino and defended the Mendrisotto, with the back-up of the Northern Defensive Line behind them.

Underground firing positions

It was all a highly unlikely scenario. A neutral Switzerland proved highly useful to both sides, not least for the aid the Swiss provided for Prisoners of War and the seriously wounded on both sides. Finally, the Germans benefitted more from the Swiss hosting of Russian Revolutionaries than invading the place, especially while Lenin was ensconced in Zurich. Whatever the Italians feared, for the Germans to invade Italy through Switzerland , the game was not worth the candle.

Inside the trenches

Even after the Italian declared war on Germany in August 1916, the threat of a German invasion through Switzerland remained improbable. As the war went on , Italian units along the northern defensive Line were progressively reduced, regular army units and heavy guns were sent to the front on the Isonzo and the Regia Guardia di Finanza took over the defensive line, after the disaster at Caporetto even those were sent to the east. After all the expenditure the Northern Line remained a white elephant and was allowed to slip into disrepair.

At the end of the fortifications you reach a small church dedicated to San Maurizio which was built in 1975 by the Alpini Group of Menaggio, in memory of the fallen in all wars. Under the church, in the bunker which is part of the fortifications of Mount Crocetta, there is the shrine where every fallen man from Menaggio is remembered. From the back of the church a viewing point gives a spectacular view over Menaggio and the lake.

The Chapel of San Maurizio

The view over Menaggio and up the Lake

The route down is pretty much the same as the way down, emerging back in Menaggio for some refreshment. The bus C10 back to Como, stops on the right hand side of the Santo Stefano Church about 100 metres further up the road. There is a clearly marked bus stop with seats and a shelter just outside a little park, Word of warning if you miss the 1700 bus back ‘you are destined to have an unscheduled aperitivo stop until the next bus at 1900. That is according to the Spring timetable, they may be more frequent in summer. As a sign of the number of tourists around Como, the bus is already fairly full at Menaggio and it is then standing room only for the passengers greeting on at Tremezzo, Villa Carlotta and Lenno

Como bus timetable for the C10 bus

Orari in tempo reale (asfautolinee.it)

Como Ferry time tables

Biglietti e orari Lago di Como - Navigazione Laghi